The inaugural iPhone was released in June of 2007. Facebook was founded in February of 2004. The iPod Classic that gave rise to that iPhone debuted in October, 2001. Google was founded in 1998, and Yahoo and Amazon both launched in 1994. The World Wide Web was released to the public in 1991.

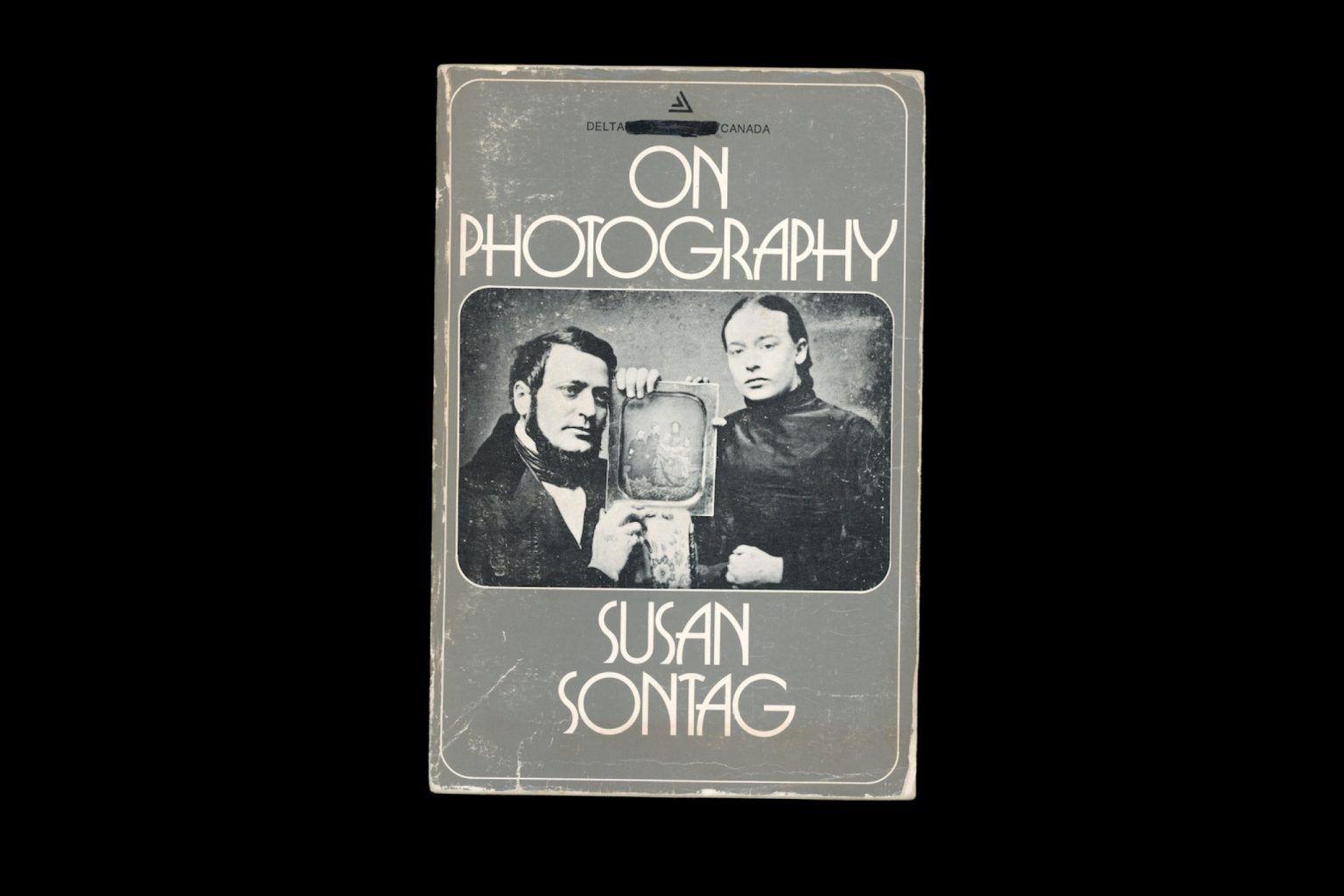

So how could the massive media consumption of the present day possibly compare to that in say, 1977? This question comes to mind when reflecting upon and being astonished at the parallels found in Susan Sontag’s collection of essays published that year, On Photography. Sontag (1933-2004) wrote of the effects of mass-imagery consumption before the Internet was even fathomable, yet her observations have proven to be more relevant than ever.

Much of Sontag’s writing in On Photography revolves around the power wielded by photographs. She argues that the quintessential nature of photographs is that they derive directly from reality such that they hold a certain authority, a certain sense of “realness” that works in other media, such as paintings, do not. Sontag writes that “Instead of just recording reality, photographs have become the norm for the way things appear to us, thereby changing the very idea of reality, and of realism.”

Furthermore, Sontag argues that the people of the late 1970s — the society she was observing — go as far as to prefer photographs to firsthand experiences. “To collect photographs is to collect the world,” she wrote. “It confirms your connection to places and objects once distant and remote, making the world slightly smaller and less alienating.” This idea of familiarity through consuming photographs is a theme explored extensively throughout the book. This is where we must pay close attention to Sontag’s observations as we “collect the world,” as we spread and consume photographs. We are currently consuming exponentially more images than people were when On Photography was published, and so her commentary has become even more relevant with each decade since it was written. Reflecting on the messages of this book can make us more aware of how we actively play into the endlessly growing global archive of images.

“The powers of photography,” Sontag wrote, have made it “less and less plausible to reflect upon our experience according to the distinction between images and things, between copies and originals.” Even as they approach their asymptotic best, photographs still exist as copies, while most of the time they are visual excerpts, framed parts of a whole. The age of social media and its ability to crop and distort said frames has made this pretty darn clear.

Some of the most deliberated-over, most highly-curated of these visual excerpts are images posted to any number of social media platforms. Whether it be a global brand promoting a popular new product, or a teenager posting a mirror-selfie, the posted photo has been carefully selected for the task of representing. We tend to choose the most flattering, aesthetically pleasing, thematically relevant content to post to our accounts, thereby constructing idealized personas. Sontag warned of how photographs “are a way of imprisoning reality, of making it stand still,” while highlighting certain details and sweeping others under the rug.

On Photography tells us that we are not passive players in this game as we actively create and disseminate images. When we capture and share images, we are authoring and editing narratives, and in different contexts, the creation of these narratives is more and less overt. For instance, Gatorade’s latest campaign, “Greatness Starts with G,” presents a pretty clear storyline: Gatorade is the path to athletic greatness. With the straightforward motive of selling Gatorade, it is easier to know that there is a message being fed to the consumers of these images.

Other applications of photography blur this line. A photograph taken and shared weeks ago shows a United States Marine soldier holding a baby in Kabul, Afghanistan. The consequences of this image are significant, as the photo seems to depict a gentle, affectionate relationship between the American soldier and the Afghan baby. This image leaves out any representation of the dozens of thousands of deaths that have resulted from the war in Afghanistan (Brown University’s Watson Institute estimates that more than 46,000 Afghan civilians have been killed in this conflict). This photograph, like all photographs, is not an objective observation. It is an excerpt selected from a larger reality.

Photographs can help convey some of that reality on an international scale, but the power of photographs to tell comparatively smaller stories remains even when we scale back down to our personal actions. Getting back to Sontag’s writings, being mindful and critical of the way we interact with floods of photographs can make us more thoughtful consumers of these images. Her argument that photographs redefine what is real is especially pertinent to what we think about when we scroll through endless social media feeds: when we see a photo posted to social media, we’re not really staring down reality. We’re seeing just the parts someone is choosing to post, a part of the larger situation. Keeping this in mind both when we see our peers’ posts, and when we consume larger scale news or advertising can help us remember what is reality and what is edited content.

Soon after On Photography was released, Sontag was interviewed by New York Times journalist Charles Simmons. Sensing that she had more praise for the art by the end of her book, he asked if her opinion on photography had changed throughout her writing process. She responded by saying that “I came to realize that I wasn’t writing about photography so much as I was writing about modernity, about the way we are now…And writing about photography is like writing about the world.” Photography was already a central part of the world forty years ago, and its role has expanded many times over since then. In order to responsibly move through this world, we have to remember what a photograph is, and what a photograph isn’t.