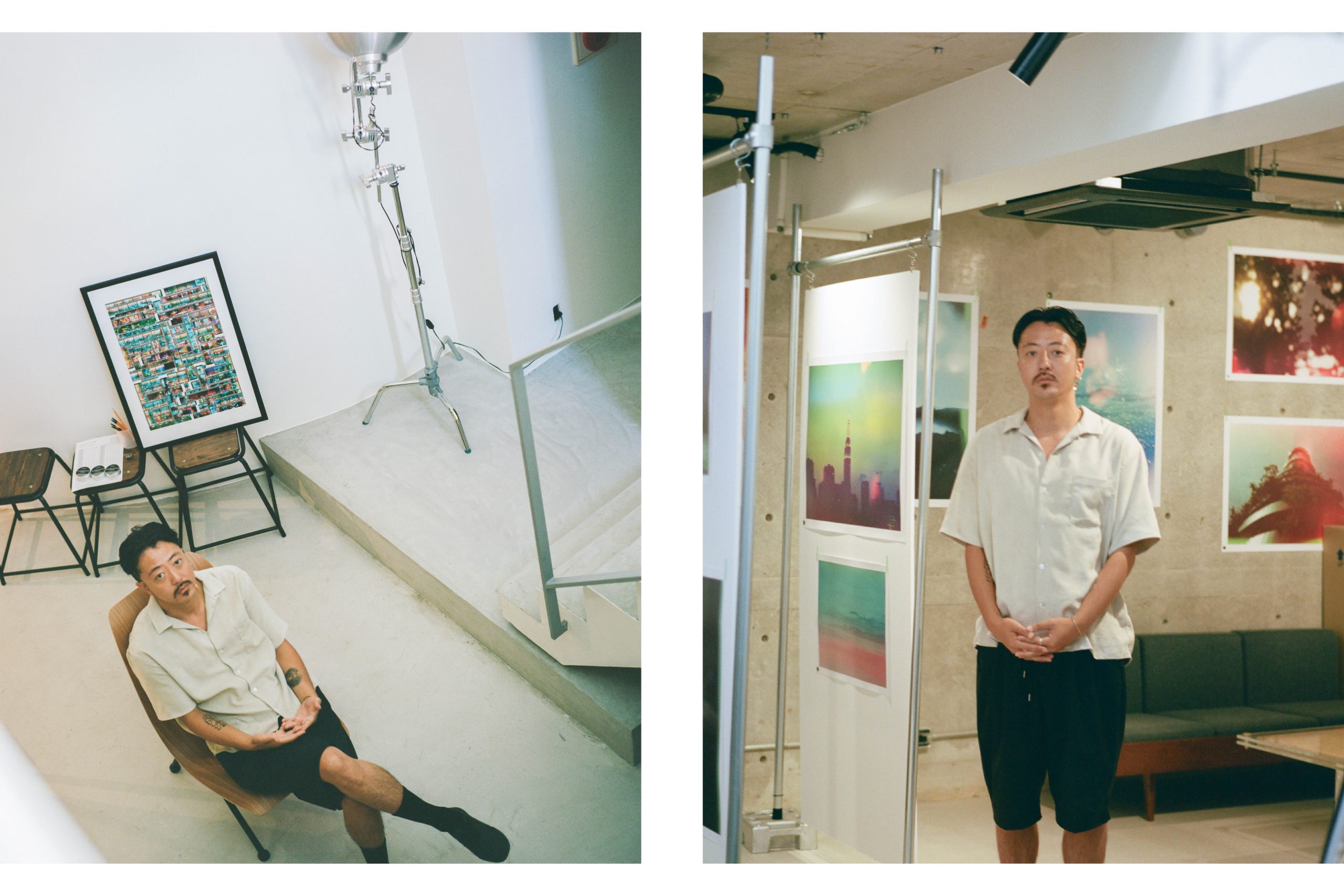

Yuma Yamashita is a self-taught photographer based in Tokyo, Japan. He talks about the impermanence of nature, and what a building has in common with a bowl of ramen.

Yuma Yamashita

I turned away for a second to find that Yuma Yamashita had already inhaled his first bowl of rice. It was noon-time and the restaurant was packed—we ordered a set lunch that came with crispy karaage, miso soup, and pickles. As a waitress disappeared into the kitchen to get a second serving, I watched him pick up individual grains from the bowl with his chopsticks. He clearly didn’t intend to miss a single piece.

Sitting in the middle of having a practice in photography and food, Yamashita is the type of person who zooms in on the details.

A friend from Tokyo once told me that residents of the city remodel their houses every few years to strengthen their structures to prepare for earthquakes. One would imagine that the cycle of construction in a landscape that is constantly on the verge of change makes people confront the transience of their spaces on the daily. We grapple with stories of the unknown on a regular basis: in the age of the disaster movie, the concept of the urban dystopia is constantly reimagined and doesn’t always feel far off.

Photography: a practice that acknowledges this impermanence. The probability of one’s coordinates, light sources, and curiosity in a moment create a frame that cannot be replicated in its entirety.

The choice to create an image becomes a collective archive: we can feel the rapid heartbeat of a city scrolling through angles of the same moment channeled through multiple screens; changing by the millisecond it takes to create a personal depiction: I am here, and also I am amongst. We document history as we live through it.

Yuma Yamashita focuses on this unknown with his camera lens: his work juxtaposes people, for scale, alongside the Japanese metropolis. The co-founder of Inspiration Cult Magazine and Gallery has a continuous stream of photographs that feed an ever-growing collection of moments, but has his roots firmly planted in tradition.

“I think photographers need a certain amount of luck,” Yamashita muses. “May it be weather, the timing of passersby—I think I have it as part of my style. It’s not contrived. I know when luck is not with me when timing doesn’t work out, and I know that’s when I pull back and walk away. I just want to naturally capture the moment that is there.”

The Shizuoka-born artist describes his self-taught approach to artwork as flat and diverse, choosing to bypass genres.

“When I first started taking photographs, I would see and emulate the works of New York photographers like 13th Witness and Trashhand, and to render something that’s foreign to Japan in my photos,” says Yamashita. “I now think that focusing on something more traditional, more uniquely Japanese will lead to something more original. And I think that’s because I grew up being exposed to such traditions [here] that make me think I can get over a certain hurdle, and to go to the next focus.”

Before landing projects with brands like Apple and Suntory Hibiki, the creative’s earliest practice started through an interest in food, creating carefully constructed bowls of noodles in a ramen shop. “There are actually similarities between the two: [when it comes to food], you make something from scratch using material at hand,” he says. “Photography too—you take something that is already there, think about it, photograph, and edit.”

Elements in each bowl had intentionality in color and composition, with consideration to the human eye. With the philosophy to take down preexisting ramen rules, the space served ‘shio’ (salt) and ‘shoyu’ (soy sauce) variants topped with bamboo shoots, pork, scallions, and egg with an added twist: tomatoes.

The added profile of flavour came through from a thoughtful process—the sourcing would change depending on the season, the chef mindful of which farm provided the best ones. The ingredient sat in an oven with olive oil before making its way into the bowl. “By adding this single essential element, he created an artwork. I think this is quite linked to photography,” said Yamashita. “May it be the composition or the coloring, it is always important to consider the essence, what is essential here.”

The amount of preparation placed into a bowl that would be consumed in under an hour: a fleeting work of art, measured by the satisfaction of the handful of visitors in front of him.

When the shop was closed on Mondays, the then-chef would explore the city and capture it through his iPhone. “This is something I learned from using a mobile device to take photographs: It’s easy to compose a good [picture], just as long as you get the golden ratio found in the Instagram square format. It’s easy to make something nice to look at, and accessible,” Yamashita says. “But if you’re creative,” he adds, “you should take that extra step or jump out of the comfort zone. When you take a photo of a puddle, you can just take a straight photo of it. Instead, take that push: stick your phone in the puddle and see what you get. All creatives, not just photographers, should take that extra step and get out of that comfort zone.”

What started out as a platform for ramen photos soon expanded as he explored more photography subjects. The budding chef once serving ramen to 6 people at a time grew into a photographer with a social media audience of more than 100,000. “May it be for them or for the [individual customers], to whom I serve carefully prepared ramen, there is no way that everyone will like what we serve,” he muses, “and it’s just not feasible to create a photo that 100% of my followers would like.”

This curiosity towards experimentation has moved Yamashita to create some of his most memorable work: themed Inspiration Cult magazine editions, with varying key words contributors would explore per issue: from “things that have been around, things that will not change”, to the idea of “risk”.

One particular issue was entitled “war and fruit”: a juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated ideas. Commissioning work from war photographer friends who regularly went to areas of conflicts alongside photographs of fruit, Yamashita hoped that people would create a link behind the visceral images of conflict alongside everyday objects by alternating them in a pattern. “For some people, I’m sure it was confusing, but we hoped they would feel a link for themselves,” he said: his assigned fruit was the cherry. “I took photos that suggested that the cherries symbolized the earth, and with blood [cherry juice] being shed in the name of money.”

What’s really troublesome, he explains, are man-caused calamities: people making tunnels, destroying the structure and causing landslides. “People bring about a lot of secondary disasters onto nature.” After the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, he started to look for a way to define “nature” through the lens of animism.

“Since civilization, Japanese people have believed in the concept [that everything is alive], has their own spirit and feelings. I think if I could capture and render that, it could perhaps be the expansion of [my] personal expression.” Yamashita explains. “Things that were previously there are washed away, even feelings, by the tsunami—but it shouldn’t be seen as tragic—the earth is alive, it’s breathing, and things like that are bound to happen.”

“There isn’t that much nature in Tokyo so even when I take photographs of buildings, I think they are alive too,” he says. “It feels like they are breathing, even if they’re not even of nature, but man-made.”

After lunch we walked to a shrine in the middle of the city. The space is a testament to our conversation: that amid the chaos of existence and the impermanence of things, we can choose to make our surroundings, and the present moment, sacred. At the entrance, there was a moment of silence. We scooped up water from a fountain with wooden tools to wash our hands before crossing the threshold.

“I think photographers need a certain amount of luck. May it be weather, the timing of passersby—I think I have it as part of my style. It’s not contrived. I know when luck is not with me when timing doesn’t work out, and I know that’s when I pull back and walk away. I just want to naturally capture the moment that is there.”

— Yuma Yamashita