The sneaker industry has reached its pinnacle of competition. It’s a boon for consumers who have a range of footwear spanning multiple sportswear giants to the small guys. This has been coupled with an increasingly quantified world that has influenced how brands approach their craft. Footwear was once a combination of performance and aesthetics, where the aesthetics represented a skillful art. Now, that task is increasingly rooted in analysis and less about intuition. We spoke with several different people representing their own take on the current process towards sneaker design and where they see the future of the industry.

A selection of FACTO shoes litter Victor Hsu’s office.

Hsu spent many years in the industry, providing him with an overview and direction for FACTO from the start.

On March 10, 2015, Facto, a new footwear brand based out of Tokyo, announced itself to the world via a single Instagram post. Below an image of the brand’s logo, founder Victor Hsu rather grandiloquently stated his manifesto: “I began to sense that culture was becoming increasingly inundated with saccharine laden, instant gratification delights, mass produced and marketed to promote a commercial cycle of gross consumption … I decided I wanted to invent something more substantial, more nourishing for the soul.”

Facto preaches an increasingly familiar luxury sneaker narrative: manufactured to meet a Japanese consumer’s exacting quality standards; designed to compete with European luxury houses; produced in Italian factories from custom lasts, the highest quality leather, and Margom soles; priced for the Common Projects set starting at $375. Affordable Luxury rage against the Fast Fashion machine.

But speaking to Hsu from his office in Tokyo, Facto seems as much a reaction to his experiences as a traditional department store buyer and mass channel brand designer as it is a reaction to fast fashion. “When I was a buyer,” Hsu said, “it was for one of the most analytically driven stores in the market. Vendors would tell us we were numbers driven instead of fashion driven. It was excessive to the point that it was paralytic.”

Hsu eventually moved to the vendor side, where he encountered the same ossifying conservatism in return from wholesale buyers. Large orders coming from large retailers like Macy’s and Nordstrom didn’t have the margin for error that would allow risk-taking, and it impacted design decisions. “Those buyers are looking for something more specific,” he explains. “After a while, when you’re working with buyers for a number of seasons and years, you base your decisions on their selling. It was difficult to break away from that, in a way.

“You can try to bring in some newness,” Hsu said, “but it can corner you. It can pigeonhole you into a certain place.”

With Facto, Hsu has been able to reverse the tides. “My first collection just launched. I didn’t have any history to work on,” he said. “I didn’t have to anniversary any numbers or base it on what sold last season. And that was refreshing for me. It’s just what I want to make really.”

Hsu still believes wholesale accounts are important to the brand for the credibility and production scale those orders provide, but he can be selective. His shoes have found their way to the shelves of a curated set of retailers around the world – Kith, Fred Segal, Bergdorf Goodman, Level Shoe District, Holt Renfrew, Lane Crawford. He’s more excited building his online store, however. “I’ve been a vendor for a lot of years, and now this brings me back to my days of being a merchant. It makes me think about my own collection.”

This freedom is, of course, merely Hsu taking advantage of present circumstance – a globally connected society and economy, unprecedented business scale, demystified manufacturing, an increasingly high profile sneaker market. It has enabled him to catapult away from the traditional footwear brand-retail ouroboros in an attempt to bend minds and wallets toward his specific way of design and thought. And he is not alone.

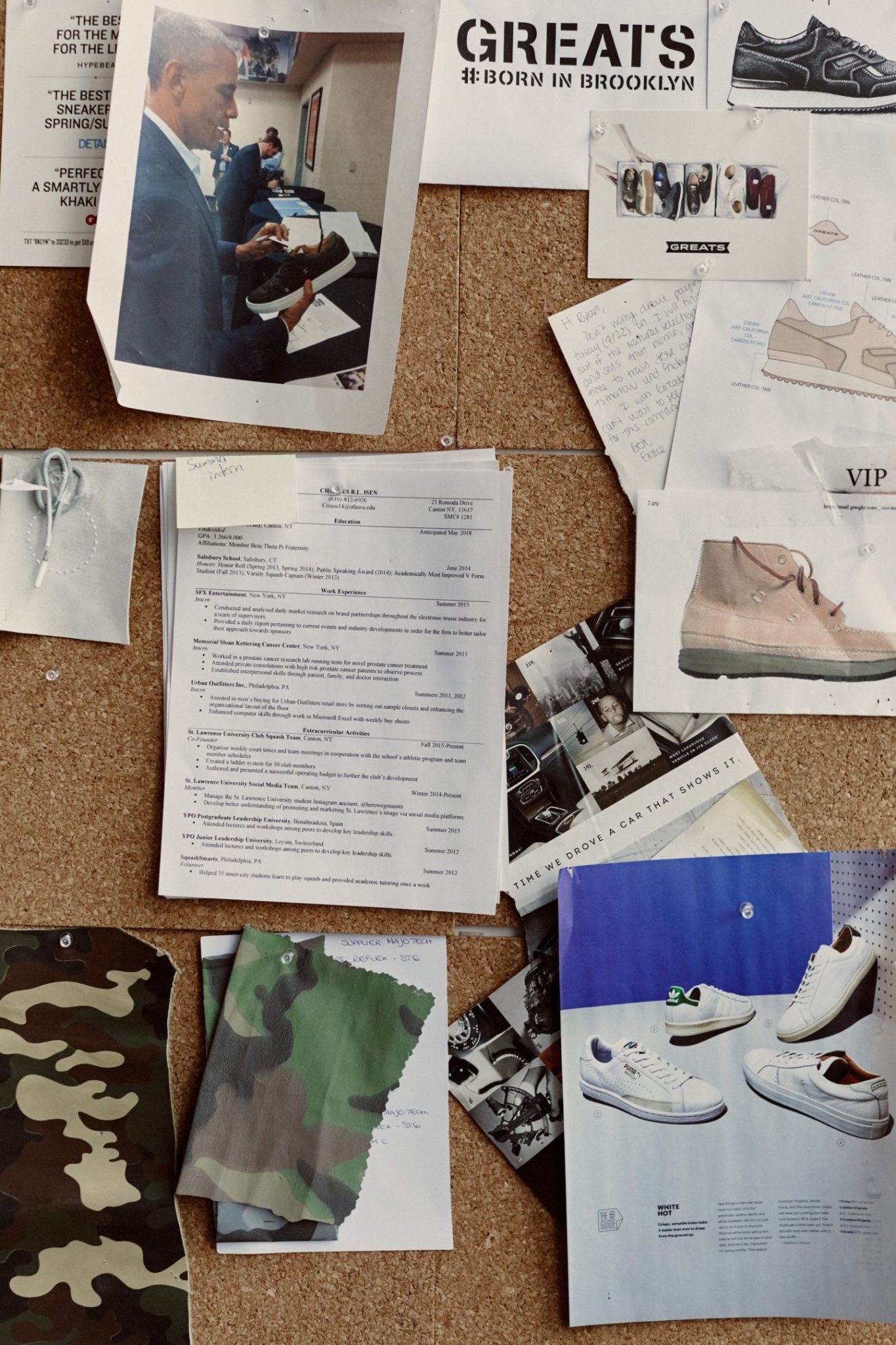

Ryan Babenzien started Greats in hopes of providing high-quality footwear at sensible prices.

“It’s the most non-optimized business I’ve ever seen.”

Ryan Babenzien, co-founder and CEO of footwear brand Greats, sees startling inefficiency in a global footwear industry he believes is ripe for disruption. And he believes his company is the disruptor.

For Babenzien, who speaks in a honed, elevator-pitch patois, the issue is clear.

“In a big sneaker company, here’s how it works: Designers, who are the eyes and ears of the street, come in with a full collection, and there is all this beautiful stuff,” he says. “And then the sales rep and the sales team go, ‘That’s amazing. I don’t think we can sell any of it, but we’ll try.’ And then none of it gets bought because the retailers are the ones who say, ‘I can’t sell that. That’s fucking hot pink. No dude is going to wear that.’ because that’s probably true for a huge section of people. It turns into this homogenous, non-differentiated market that puts pressure on the retailer. And then the brand has to worry whether they merchandise it right or not. And that’s why we’re doing it this way.”

Greats’ “way” – forgoing traditional retail partnerships to directly sell relatively small runs of product to consumers at affordable prices – is not new or revolutionary. But it gives Greats the flexibility to put their exact designs into production with the materials they want with control over the product story.

To Babenzien, his team’s greatest skill is interpreting proprietary and public information to deliver footwear designs consumers will want faster and better than competitors. “It’s part art, part science. All this information is out there in the world for me and everybody else. I think we’re just that much better at interpreting it.”

While reluctant to detail exactly what this process entails in practical terms, Babenzien says his team has built forecasting models based on internal and external data. He provides the Canarsee sandal as an illustrative example of the creative process.

“We know Birkenstock continues to grow; we know on the other pole, visvim is doing this insane shit for $800 that looks like a life raft on a sandal. And we know that our core customer loves visvim but generally can’t afford that.” This understanding of their consumer resulted in a military-minded, sportier Birkenstock-style sandal made in Italy but sold at a fraction of the price of visvim’s Christo.

“Greats’ ‘way’ – forgoing traditional retail partnerships to directly sell relatively small runs of product to consumers at affordable prices – is not new or revolutionary. But it gives Greats the flexibility to put their exact designs into production with the materials they want with control over the product story.”

The Canarsee’s launch was also fortuitously given a boost by Bill Cunningham of the New York Times photographing Nick Wooster wearing the sandal at New York Men’s Fashion Week. “That was magic. You do enough art, you’ll get some magic results.” The Canarsee sandal sold out in a week.

Babenzien believes over 70% of the brand’s releases have connected in a similar fashion. And Greats is winning on other fronts, too. The brand has attracted a steady stream of enviable collaborators, including United Arrows, Orley, and a forthcoming release with Noah, the fledgling brand of former Supreme creative director (and Babenzien’s brother) Brendon Babenzien. E-commerce enterprise software giant Shopify recently released a custom-designed app for the brand, choosing Greats from amongst its quarter of a million clients for the project. There appears to be sincere megabrand flattery in how the recent Vans x Engineered Garments collaboration seems to reflect Greats’ own Wooster-designed Lardini collection from last year.

All of this success is in spite of the fact that Greats doesn’t currently employ any actual career footwear designers: co-founder Jon Buscemi left to focus on his own brand, and the company also parted ways with design director Salehe Bembury in late 2015. But Babenzien, whose background is in footwear marketing, is undeterred by this; his confidence in his company’s prospects is as bold as it is inarguable.

“We have as good an opportunity as anyone who ever launched a vertical brand to be in the unicorn club.”

Unlike Babenzien, Jon Tang, a career footwear designer and self-proclaimed Bauhaus-style design purist, believes a footwear brand, especially a new one, needs an experienced footwear designer at its core. And unlike Greats, his new outdoor brand Fronteer has extremely modest, almost amorphous goals. “It’ll grow as it grows, and if it becomes successful, that’s great. If not, it is what it is,” he says. “Whether or not people like it, I want to make something to share and that is it. I’m not doing it for ‘likes’.”

Tang also takes a more measured view of the brand-retail dynamic than Babenzien. This is likely because Tang, who has designed shoes for Puma and K-Swiss and whose current “day job” is lead footwear designer for Kith, has been fortunate during his career to work mostly on “blue sky projects” – at Puma, his group worked on special projects that gave them broad creative license. He was brought in to K-Swiss to help re-launch and re-imagine the brand in a new direction. He recognizes that large, global brands can do good work.

But even those positive experiences were born from a malaise of conservatism. The broader environment at Puma was one where, “everything was consumer-based, and ‘retailers were only asking for this and so we’re going to do that’.” His team took an inch of freedom from management and ran with it successfully. At K-Swiss, the relaunch was only initiated because new ownership was seeking to jolt the brand from mediocrity.

Thus, Tang sees the limitations – at a large brand, there generally just isn’t the appetite or capacity to take the sort of design risks Tang has the confidence to take at this stage of his career. “As I became more knowledgeable in the field, I wanted, to be honest, to do crazier and crazier stuff,” he says.

“In the end that’s why I wanted to start my own brand. With my own brand now I can take all the risk I want.”

But those risks are still calculated. Tang believes as brands and their products evolve, knowing your roots while moving forward incrementally is key. Consumers crave change, but balance is critical to creating products consumers can digest. Tang has labeled this dynamic between conservative and liberal forces in design “recontextualization through familiarization.” He defines this as the experience created by placing the familiar in a fresh and different context, and it is fundamentally central to his concept of design.

Simultaneously, he believes that consideration of customer interests can only take you so far. “We didn’t know we wanted an iPod until it came, which is why consumer feedback is only so useful. It can’t tell you what the next big thing is. You should never ask consumers for the next big thing.”

Even at this early stage, Tang’s experience with Fronteer is illustrative of this philosophical push-and-pull. His first priority was that the brand exists as a catalyst for analog exploration and personal discovery in our digital world. Business concerns were a distant second. He hoped to express this in not only product but in the entire brand experience, which he tried to effect by using purposeful obfuscation – the brand’s Instagram account acting only as an abstract outdoors-themed mood board, limited access to product photos, a web shop that needed some interaction in order to make a purchase.

But he’s realized at this stage, the market isn’t ready for that version of his vision. “I think I needed to build the brand for the initial digestion to be a little bit easier,” he admits. “Once I have a vision people can see and know, I can keep them on their toes by offering a new take and set-up by offering these analog ideas later.” Fronteer’s Instragram now shares its story with stark transparency, right down to the particulars of logo design and font selection, which Tang hopes will inspire creativity and entrepreneurship in his customers. The website now has a conventional webstore attached.

Tang insists the brand experience will continue to evolve back toward his initial vision as it grows and its center of gravity shifts. “I’m basically waiting for that point where I have developed the brand enough to be able to do something more interactive with discovery elements and live streaming in some sense. I see that as a part of the future and vision of what the interactive level of a brand can be.”

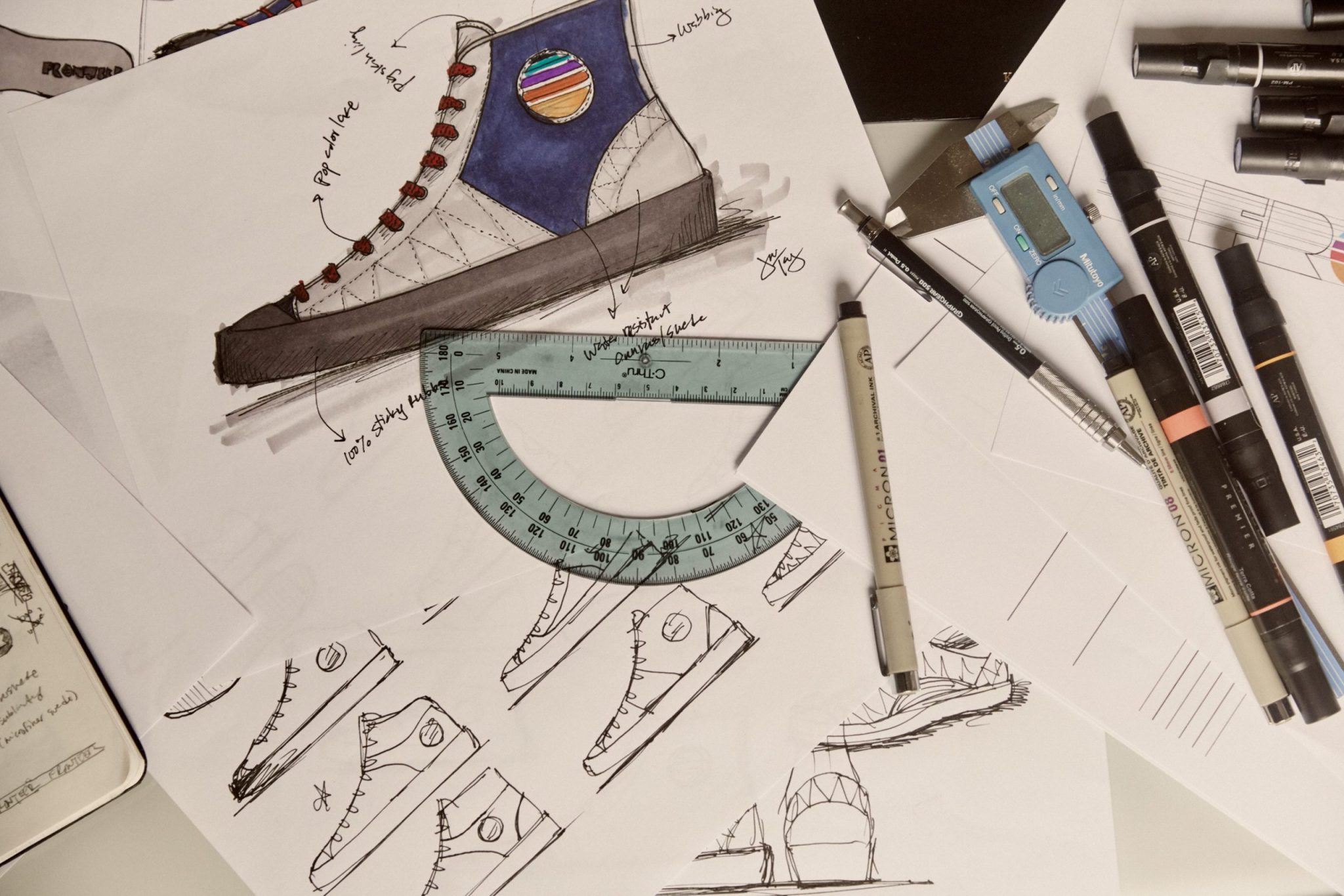

Early sketches of Jon’s first season releases for Fronteer.

In 2014, Jason Mayden surprised many in the footwear industry by leaving his post as Global Design Director for Nike’s Jordan Brand, a position he’d risen to after 13 years of working closely with luminaries like Michael Jordan and Derek Jeter. But the biggest surprise wasn’t the place he was leaving; it was where he was going: a small Silicon Valley start-up called Mark One.

After a nine month stint there that he says “authenticated” him in the Silicon Valley venture capital community, Mayden continued to carve a career path beyond categorization. First he jumped to noted venture capital firm Accel Partners to take an undefined design role. He wasn’t joining a fly-by-night operation – Accel is a global firm with billions in investor capital and an investment portfolio that reads like a murderers’ row of Silicon Valley successes: facebook, Dropbox, slack, Spotify, venmo, myfitnesspal, Kayak, Etsy, Squarespace. Then in early March, he leveraged his Accel and Nike experiences to become Chief Product Officer and co-founder of Slyce, a new media company he launched with fellow Nike alum Bryant Barr and Barr’s college roommate and NBA superpower Stephen Curry.

There is an unscripted poetry to the concentric circles now forming in Mayden’s working life. But it is still an unorthodox path for someone who originally held what many in the sneaker industry, including him, would consider a dream job.

“There was no amount of schooling that could prepare me to make this move, it all kind of came down to instinct and gut and recognizing that if I wanted to survive and compete at the level I wanted to compete, I had to make a shift, I had to develop a skillset that was non-typical for my industry.” His survival instinct was triggered by the realization that footwear companies had a new set of formidable competitors – market disrupting tech businesses. “If you’re not trying to figure out how technology companies compete, then you’re going to fall behind quickly.”

He believes the shift has already put him “probably about 10 years ahead of where the Nikes and the Reeboks and the Underarmours even can start thinking about creating for athletes.”

The central problem he identifies with the traditional footwear industry is by now a familiar one: trend forecasting and designing based on historical performance, retailer preference, and trend spotting. His team’s worldview was, for all intents and purposes, backward looking.

After 13 years at Jordan Brand and Nike, Jason Mayden came away with a profound understanding of the footwear industry.

“If you’re not trying to figure out how technology companies compete, then you’re going to fall behind quickly.”

In his new roles, the lens he sees the world through has expanded exponentially, giving him the ability to have better perspective on future product and business trends.

“On this end of the spectrum, I’m looking at the global market trends. I’m looking at micro and macroeconomics, and how technology is creating new economies that will include footwear. So when you’re able to see the economy, it’s real easy to see what product is going to work in that economy. When you see the product but you don’t understand the economy, it’s really hard to see how you can carve out value in the future,” he says.

“I am getting information that the average designer doesn’t have access to,” Mayden explains. “And it’s really changing the way I view my process.”

www.fahimkassam.com

Through Accel, Mayden has moved from designing products to helping design businesses and lives. He is tasked with being a voice for youth culture and under-represented communities in an “industry desperately looking for people to invest in”; beyond that, the role is his to create. He is building a “phase zero” start-up generator that inspires young “cultural alchemists” to design products and build businesses for the future by exposing and immersing them in experiences outside of their normal environments.

And with Slyce, Mayden is, in a sense, revisiting a process with which he is intimately familiar from his time at Nike: building celebrity through product, only this time that product is the celebrities themselves. “We want to create a really simple, frictionless experience for the influencer to be able to tell authentic narratives to their audience and drive value that is not only impactful to the audience but to the people creating the content – the influencers themselves,” he says. “We’re going to bring a tech component in an industry that’s been very, very managed by manual entry and lack of real data.”

In both roles, Mayden wants to be a bridge between the cultural expertise of streetwear companies and the data expertise of technology companies. While there is difference in process between those two worlds, he sees his duty as a designer as fundamentally the same. “I use data as a medium, the same way I use paint or pixels or leather. Data is just another way for me to create unexpected products that innovate in ways that people never thought.

“If people like us, people like myself, can convince more people to start making this jump or at least learning about it, then I think we can make way better products in the future.”

Greats moodboard

Fronteer sketches

Innovation and disruption in industries is not clean, predictable, or singular. It comes in fits and starts, with dead-ends and unforeseen twists. On October 7, 2015, adidas released a video teasing Futurecraft 3D, a shoe with a 3-D printed midsole. A week later, Nike was granted a patent for 3-D printing shoe technology. A future where brands sell designs while manufacturing is, at least partially, done at home is not impossible. “That’s real; that probably happens on some scale. It’s a ways away and the sneaker business isn’t going to evaporate tomorrow, but it’s real,” says Babenzien.

Meanwhile, New Balance has launched “Digital Sport”, a division that joins Under Armour’s “Connected Fitness” in the race to develop wearable technology to provide analytics to users.

This is indicative of the unpredictability of the shape of the footwear industry and, by extension, entire consumer product industry to come. Nothing is guaranteed. It is an inkblot with innumerable interpretations.

Hsu, Babenzien, Tang, and Mayden each left enviable roles in the footwear world of old to look into that inkblot and push their own design narratives forward. Propelled by new technology, a new economy, and the relatively new prestige of the jobs they left behind, they are situated along various points of the bleeding edge of design and commerce, creating a world around them as they see fit. Their ideas and design philosophies are not harmonious, nor is their success or failure mutually exclusive.

And no one is arguing that large brands, charged with producing things people want to buy, or large retailers, charged with stocking things people want to buy, don’t provide a useful service or aren’t skilled in providing those services. But it’s certainly true that in our brave new world they aren’t the only solution.

“It’s a new day man,” says Mayden. “It’s the wild, wild west right now.”