Alex Valdman has worked diligently and embraced the bumps and bruises of innovating in fashion and design. His early path in fashion was driven by the vanity of working with the likes of Kanye West and Nike, but in time he recognized vanity’s detrimental effects on a creator’s ultimate path.

Fashion’s greatest role serves as a signal to the outside world. What you wear, how you wear it, and the fit itself could all be collective cues towards a deeper narrative. But when the signals sent to others as a form of vanity become the dominant reason to explore fashion, can it have underlying and detrimental creative effects?

Alex Valdman’s early interactions with San Francisco’s vibrant skate culture would establish his perspective on what community and authenticity would entail. It would force him to establish an opinion that would serve as the backbone of developing an eye for design and an appetite for the creative struggle.

Connecting with Alex Valdman, Creative Director at Rapha, led us on his path from independent designer and brand owner, to overseeing one of cycling’s most respected clothing labels with eye-opening stops along the way with Kanye West, Nike, Levi’s, and more.

Alex Valdman: Hong Kong. Drunk at Ronin.

Eugene Kan: No, wait, how long ago was that?

Alex: Three years ago.

Eugene: It’s been three years?

Alex: Two and a half years.

Eugene: Two and a half years.

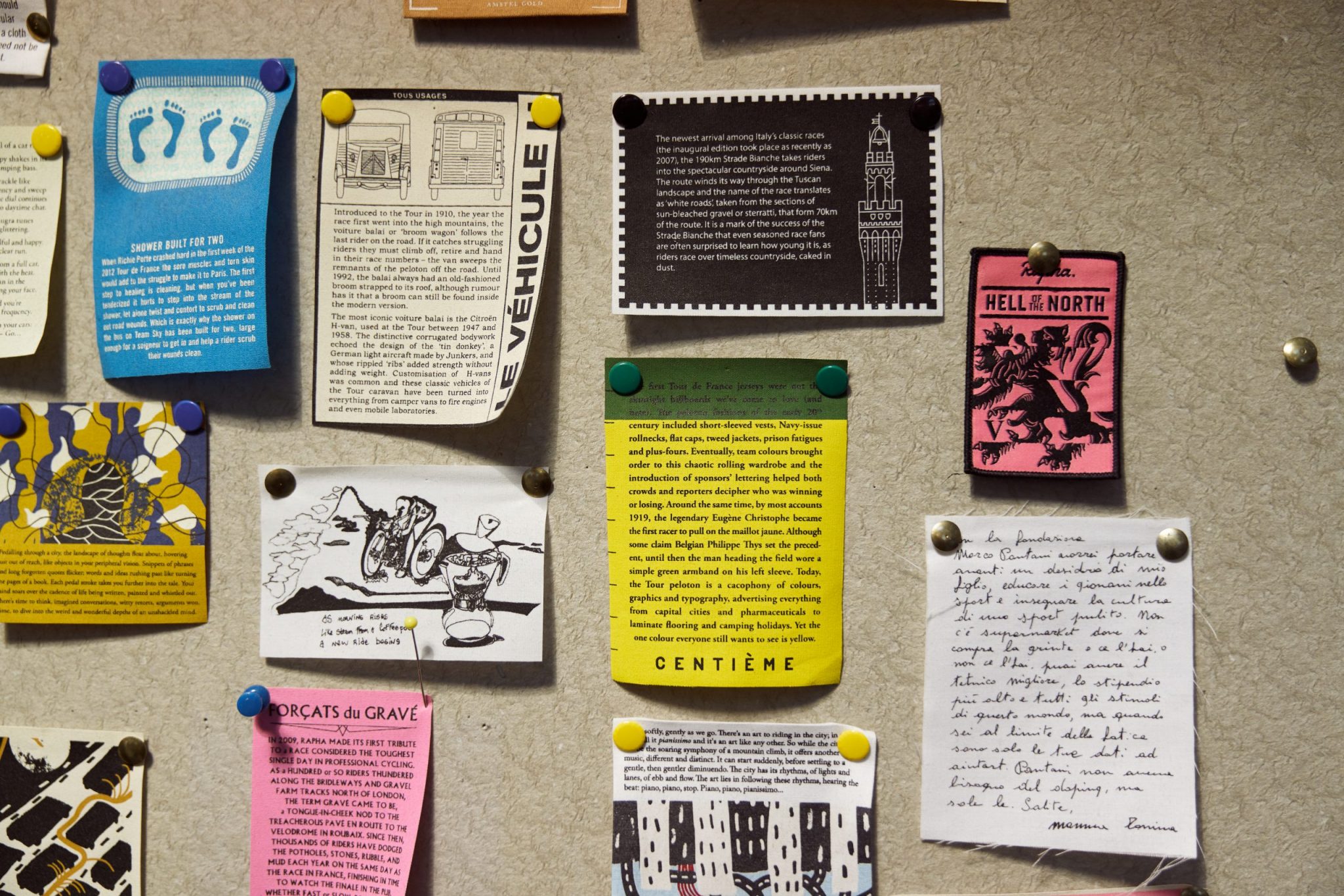

Eugene: I’m sitting in the cozy office at the headquarters of Rapha in London’s Kings Cross area. I’m catching up with an old friend, Alex Valdman. As Rapha’s creative director he’s helped the brand transcend cycling and become globally respected thanks to its branding, marketing, and, naturally, a highly desirable product that includes a network of brick and mortar clubhouses across the world.

These clubhouses around the world, and as far as Taipei and L.A., allow global Rapha members to pop in for a quick coffee, to borrow a bike, or to meet with a like-minded community. I’m actually not here entirely because of Rapha, but instead, I’m here for Alex’s fascinating trajectory that started with him making custom hoodies for the likes of Kanye West with his own brand to entering the corporate world with time spent with Nike, Levi’s, and Giro. His story is about realism and reinvention.

Eugene: So you and I met 2005, 2006?

Alex: Yeah.

Eugene: Something like that. In the most sort of… I guess at the time it made a lot of sense. We met on MySpace and I had just started at HYPEBEAST and I was, like, “Oh this is kind of cool, like someone’s hitting me up for HYPEBEAST related stuff.” How did you come across me?

Alex: I think I was on HYPEBEAST and I saw that there was an article written by Eugene Kan that I really liked. I forgot what the article was about. I wish I could remember.

Eugene: I wish we could open up MySpace and see that initial interaction.

Alex: Yeah, I deleted my MySpace and then they went out of business anyway.

Eugene: I think they’re still around actually.

Alex: Really?

Eugene: I think they’re like a music streaming thing.

Alex: I really wonder what their business model looks like right now.

Eugene: Yeah, I wonder where Tom’s at?

Alex: Man, I know at Dover Street there’s t shirts with Tom’s face on it.

Eugene: Oh yeah! What brand is that? I saw that some place.

Alex: I was thinking, man, if I bought this and I came in here with my team all the people in my team that are under 25 would they know what that is.

Eugene: Yeah, and would they be like, “Whoa, this is weird. Why is this lo-fi super pixellated photo on this shirt?”

Alex: I don’t know if anyone’s actually met Tom. But, thank you Tom, if you’re listening to this.

Eugene: Yeah, Tom is the reason why we met.

Alex: So big shout out to Tom.

Eugene: It’s interesting because I always look back at some of the friendships I made very early on in my quote-unquote professional career and those early friendships are arguably the ones that you still keep around. People like yourself, it’s been 12 years.

Alex: Yeah.

Eugene: A few days ago, right before I came to London we were sort of reconnecting on the past and also how we followed each other’s career. I think there’s a part of us that sort of grew apart when you left the streetwear world.

That’s when we no longer worked together as closely on a professional level. I think despite that, it was always really refreshing to see someone come from that space, carve out their lane, and develop their own path.

“The more I can do to help people get into the sport, bring barriers down, innovate, push technology, and create a platform that makes it easy for people to put down their phones and do something that is positive for themselves—that’s the journey I want to take.”

— Alex Valdman

Eugene: While the modern dialogue of fashion inevitably involves streetwear, there was a point in time when streetwear had yet to intersect with an element of luxury. The high-fashion houses weren’t knocking on the door and looking to swoop in on the authenticity of street culture and hip-hop.

Alex’s interest in the development of culture all began in his younger days. San Francisco’s passionate skate community set a foundation for his path towards community and fashion.

Alex: Guess I could take it a bit back, even before HomeRoom. I grew up in San Francisco and I grew up kind of in this neighborhood that wasn’t necessarily anything but middle class—like middle class in an American sense, not the UK sense.

And it was just, I don’t know, it was just a bunch of immigrants and kids and that neighborhood just happened to have really good skate spots and so that’s what I got into. I think through skating you kind of start at an early age building this community that was super opinionated or really critical about what’s acceptable and what’s not.

You started walking this really thin line within a culture. And I think naturally that kind of grew into, “You got to have a board that’s seven and a quarter, you can’t really ride boards that are eights.” This is, like, early mid-90s.

But then something iconic kind of happened which was you had this scene that kind of came back. Becasue skating was dead in the early 90s and in the mid-90s it really kind of flourished.

To see it go from this thing that didn’t exist to this thing that existed and had been heavily influenced globally by your little community, it just showed you, fuck man, people with passion have the power to do something impactful that benefits people.

This was way better than hanging out playing video games. This is you cracking jokes with people, going through your adolescence, and building real relationships through experience.

Eugene: Which I think is the one thing that is a little bit challenging currently. You’re in a space now where entry into a community is predicated on consumption versus experience and some sort of actionable thing. You can’t really enter the world of skating without skating.

You can wear the right clothes or the right brands or you could carry a board around, but I don’t think that’s indicative. People see right through it, right. So I think that’s what is kind of interesting, because we’ve seen such a massive shift in subcultures and how people interact with them. To the point where the lack of friction means it almost doesn’t mean anything. It’s so easy for me to jump into something just because I have the necessary funds to acquire it.

Alex: Yeah and that’s really sad.

Eugene: The very first taste of entrepreneurship began with HomeRoom clothing, a small brand focused on custom hoodies in unique and often deadstock fabrics.

Alex: As my first project, that failed miserably, but I had a lot of fun and learned a lot.

Eugene: Do your really think it was a failure though?

Alex: No, I mean at the time when I had to close it down, because the economy slumped, man. it was the greatest lesson that I ever learned about how to start a company.

It was a great lesson in branding; it was a great lesson in design; it was a great lesson in relationships and management; funding. It set me up, so no, it wasn’t a failure, but it did feel like it when I had to shut it down or risk just exposing myself completely to the uncertainty of a failing economy.

Eugene: This is more for me to contextualize sort of where I was at the time. I guess for me the thing that defined HomeRoom was high-quality hoodies that had unique fabrics, unique sort of aesthetics.

There was actually a deeper design element. I wouldn’t say you were necessarily pushing the boundaries of what a hoodie was, it was just a little more thoughtful approach to fabric selection, for example.

Alex: Yeah, it was very early years as a designer. We were just doing things that were expressive and things that create tribalism where you can connect with people. If you see someone else wearing it you kind of give them a nod and, you know, right. The thing that made it really interesting was how many rappers started…

Eugene: Yeah, I was going to dip into this. I was going to push it that way just so people can understand. What do you think is the one moment where you can look back on as, “Hey, you remember that?”.

Alex: Yeah. It was three weeks into starting the brand, Kanye had it on. And it was, like, this brand’s been around for three weeks and Kanye’s wearing it.

Eugene: What would have happened if that had occurred in 2017? I mean, I think that would have changed its trajectory, right.

Alex: Yeah, you’d be like Anti Social.

Eugene: Anti Social on… was it Kim?

Alex: Yeah.

Eugene: Something similar.

Alex: Yeah. Something like that. But it wasn’t about that, right. It wasn’t about, “He’s wearing something with a logo on it.” It was more like no one knew what it was. It was like, “Where do I get it?” It was super nondescript. My stuff never had any kind of branding overtly on the exterior.

The people that were in the know were, like, “Oh, that’s cool, because it’s like no one knows what it is, but maybe I know.” That’s really kind of pithy in a way. It’s not important at all. But as a 23-year-old, it was just cool. I literally admired the music so much. I probably played it every day in my car in the form of a CD and I had so much love for his music. It opened up loads of doors, you know.

It opened up relationships; it opened up boutiques; it opened up learning experiences. It showed me I have a very long way to go to achieve my goals. And it’s still been, I don’t know, 12 years, 13 years of nothing but 60 to 80 hour weeks doing what I’m passionate about.

I think Homes set me on the right path and the people that I did it with were super supportive of it. I think if the economy didn’t explode and our accounts didn’t stop paying us it’d still be going.

Eugene: Right place, wrong time is a way to look at the ultimate demise of HomeRoom. But there’s often a respect for those that have gone out and tried to do it themselves. The failure can be bitter, but you can believe that there’s value that reveals itself down the line through new opportunities.

From here our conversation starts to go down a deeper route and it begins with some of the philosophical underpinnings that have enabled Alex along the way.

“When you work on something that gives so much back to you, helps transform your life, and when you innovate helps transform other people’s lives—that feels like I’m making a positive impact.”

Alex: It’s a journey of shedding your vanity in order to expose what is the truth. And I think everyone’s journey as they mature is just like, “What is real? What is truth?” And that just comes from being curious about everything and trying to unpick people’s dogma and trying to unpick influence, because this world is driven by economy and consumerism and it’s not a considered approach. It’s not how society should behave.

Eugene: That’s shedding vanity. Is that something that was learned or is that something you always had and was that a byproduct of growing up in the skate community where everyone was sort of challenging, “Is this legitimate? Is this real? Is this valid?”

Alex: Yeah, I think that’s a good point. I mean, it definitely comes from this notion of if you are going to go and write, like if you’re a tagger, if you’re into art with a spray paint can, but if you’re doing it you have to be doing it for the right reasons. There were people who were doing it for vanity reasons, just getting ups.

There was the kind of stuff that was really inspiring, thought-provoking, great technique, pushing the boundaries of what getting up was. Then there were people that were just kind of a toy and just doing it in volume and so it was about quantity instead of quality.

And I think shedding vanity is about finding the quality not the quantity, because it’s really easy to fill up your closet or your mind. It’s really easy to fill your mind with shit that doesn’t matter, so how can you simplify your life. And I think that has to start with questioning what you’re doing. Why are you supporting that brand? Does that brand have values that align with how you want to pursue your life?

Eugene: Alex’s enterprising nature meant that he wouldn’t be out of work for long after HomeRoom. His spirit combined with a purpose for his efforts would compound to form a perspective that would lead him to increasingly bigger roles.

Alex: But that journey of shedding vanity, basically from HomeRoom I went and did some freelance for Nike. That was amazing, but I had to ask myself is this making a difference. From that I actually went to go work for Kanye.

I just happened to pick the right e-mail account and sent him a photo of him wearing the hoodie and he was like, “Yeah man, come to L.A.” And I was in L.A. the next day. We worked on Pastelle, never released, and we worked on a GAP project that never released and a few other projects.

Eugene: Pre-Make America Great Again Kanye West has been known in the past to start projects that sometimes never release while things may have changed considerably, ranging from philosophies to political positioning, Alex’s early experiences with Kanye provided him access to an incredible creative mind.

Alex: I learned a lot about art direction from him, because that’s his strength. He can see the talent in people and assemble and orchestrate the right mixture of strengths that can overcome the group’s weaknesses and I think that’s what a really good art director/creative director does. I don’t see him as a musician, I see him as a proper CD.

Eugene: From each experience Alex continued to close door after door to arrive at his own perspective on what he wanted to do and what was his actual vision.

Alex: The story of shedding vanity, for me, as you know, HomeRoom was a vanity project; working for Nike on a few things was a vanity project; working for Kanye was a super vanity project. At the same time, when I was there it became, like, “Oh, this guy’s a genius.”

What I can absorb here I just need to be quiet and absorb. That was just an amazing moment. I remember seeing people coming in to pitch videos and instead of doing it with a deck. They came in with a dolly full of books and post-it notes on them and instead of flipping through slides they flipped through books.

I think that was the first time I was exposed to a proper creative pitch from a professional. It definitely opened up the horizon of how to communicate visually. It started off as a vanity project and turned into an educational platform. Going to Levi’s I was exposed to technical design there because we went from designing kind of traditional workwear to doing this commuter project.

This commuter project was the first time I worked on technical yarns, different chemicals, sustainability, and it opened up my mind to this world of performance. When I started working on performance I decided that I don’t want to do fashion anymore and that was the first step towards shedding vanity.

Eugene: Okay, enough about vanity and the vapidness in fashion. It’s not that fashion is inherently bad or evil as we’ve made it out to be, but rather that there’s something there beneath the superficiality that can actually be incredibly powerful and incredibly inspiring. This deeper meaning as part of community and cultural impact is something that sticks with you beyond trends.

“I think everyone’s journey as they mature is, ‘What is real? What is truth?’ That comes from being curious about everything and trying to unpick people’s dogma and trying to unpick influence.”

Alex: When you work on something that gives so much back to you, that helps transform your life, and in turn, when you innovate and it helps transform other people’s lives that sort of feels like I’m making a positive impact—starting to feel. I think there’s still a very long way to go. It wasn’t about trend it wasn’t about creating a void in people’s lives because they don’t have the latest silhouette or the latest logo or the latest color.

Eugene: I recall you mentioned something that stuck with me. Fashion sort of perpetuates this feeling of inadequacy. That is basically how fashion exists. And this is a bit of a tangent, but, you know, there’s part of me and within my career where I stepped away and I, for about 18 months, had a massive disdain for fashion. I didn’t understand it, I guess, you could almost go to that degree.

Then I soon realized my inability to understand it was because of my inability to empathize with why people like fashion. I think it really comes down to… you’re seeking identity, you’re trying to communicate a status—that status could mean a lot of things, it could mean a financial status, it could mean an intellectual status, because you have a shirt from the New York Times. I think that’s when I started to grow interested in fashion again under that pretense, because I soon understood why so many people are so rabid about it.

Alex: I mean it’s interesting, right, because from my shoes when I think about the work that you’ve done previously to this new endeavor it very much drove consumer culture.

Eugene: Yeah.

Alex: When I think about the forums that we used to be involved in, those forms were all about geeking out on the details of consumer culture. It was almost another layer down into what made something authentic that didn’t necessarily serve a function.

Like what makes Acronym authentic? Those were the debates. To your point, I think that’s why we still have friendships with those people from the forums. I just met Cotton Duck, who I guess I’ve known for 12 years, last year.

Eugene: Yeah.

Alex: Last year, it was like someone said, “Hey, this is Sam!” and I was like, “No, that’s Cotton Duck.”

Eugene: Is Cotton Duck that dude who used to dress like he was a railroad conductor? Is that the guy?

Alex: Yeah.

Eugene: Yeah, Superfuture.

Eugene: Superfuture and forums in general may have lost a bit of influence in a post-forum era of

subcultures. But the relationships that have been created are not lost on Alex and some of the previous people we’ve featured on MAEKAN.

Our way of describing Superfuture? It’s where people hang out that are better dressed than you, have more money than you, and are more knowledgeable about clothes than you. But when you dig deeper you realize that it’s a passionate community of people that welcomes discussion about every single facet of fashion from inspiration construction to cultural impact.

Alex: Superfuture is great. I’m still friends with a lot of those people and I think it’s because it was about trying to find authenticity, getting past the vanity of fashion. And I think that’s really important. But how do you feel about kind of creating that world?

Eugene: For anyone that knows my past experiences and interacted with me under those contexts, part of my personal reflection and the connection of fashion and consumerism can naturally seep into the conversation. It makes sense. The dialogue we have runs counter to the previous role that I played in facilitating a lot of this mindless consumerism we now question.

There is part of me within that whole space that I was always trying to find a way to justify why I was doing it. Actually for the longest time I knew exactly why I was in it. I was in it for the stories and I was in it for what I deemed to be this mystical ability to take something in your mind that is intangible and then find a way to bring into the real world.

That to me was my justification, but it soon got to the point where when the storytelling element maybe could no longer be brought to the forefront and it was just like, “Hey, there’s no point in even focusing on this because we don’t need to.” I think that’s when I really started to lose the plot a bit. I was like, “This is not me.” I always used this example: if you owned 50 pairs of sneakers, my goal was to really sell you on buying a 51st pair. That to me was not a quote on quote legacy that I wanted to define for myself. I think it’s interesting because everything you said about always questioning what you believe to be true is 100 percent valid.

I think that air of skepticism before agreement is something that’s missing. There’s nothing wrong with rolling up to anything anyone says and shading it, before you sort of like understand, “Okay, yeah, it’s valid.” I don’t think that exists. Everyone’s so quick to accept everything to be true or not do their due diligence to figure out if it’s real or not. I think that also was part of the mainstream approach that Hypebeast was taking. It was like it needs sort of this celebrity push.

Also I look back on it and I don’t think I was the right person to bring HYPEBEAST to where it is now. There was a time and place for me to be the other side and really double down on, “Hey guys, let’s not play that game.” Honestly, that game is probably what was needed to go to the next level. I just wasn’t the right person to do it. I just couldn’t do it within myself.

“Shedding vanity is about finding the quality not the quantity, because it’s really easy to fill up your closet or your mind with shit that doesn’t matter. How can you simplify your life?”

Eugene: When you’re faced with the idea that actions should aim for a sense of purpose it can open up some interesting insights and challenges.

Alex: If you have full integrity or 90 percent integrity versus 20 percent integrity the rewards and the spoils are much different. It almost feels like more integrity you have it limits your ability to be successful within any kind of our respective industries.

Eugene: What would an example of that be?

Alex: I think when designers pretend that they’re designers and designing a range, but it’s really they’re the face of a really big fashion house that’s backing them. They’re preaching design values without knowing what they’re saying and they just sound silly to people who have dedicated their lives to the process of creation, innovation, and transforming our world.

I think it’s a slap in the face and I feel like a lot of them are just doing it for fame and profits. I’m not going to say any names, because I don’t know their whole story and their background, but at least that’s how it’s appearing through every kind of media outlet that I encounter.

They haven’t done anything to show that they’re legit and they have a really big audience. The reason I have a beef with it is because they have the power to make a positive impact, but they’re choosing to use their influence to drive consumer culture into a frenzy. They’re not preaching a message of social relevance or humanitarian relevance and they’re doing it for personal gain. And I have a problem with people who have a platform who are self-serving.

Eugene: A point of contention is that in a resource heavy industry like fashion how does one justify what they create. And in the case of Rapha and Alex what does it mean to create comparatively expensive cycling gear?

So just to challenge that thought, because I think I generally am in agreement with that, but if I was to be on the flipside how do you look at that when you work at Rapha.

You also have these amazing products that are, by price alone, maybe cuts a certain segment out. What is your sort of vantage point on that? How does Rapha push against everything you said and have an underlying purpose?

Alex: I think that’s a really good question. For me the thing that I love more than anything is seeing when people can connect together that are like-minded. What an activity does is it allows you to move to a city and find someone else who’s passionate about that activity.

They start forming a little community and then as you get introduced to other people you start forming a bigger community. What, as you know as someone who plays sports, when you have that kind of slightly traumatic physical experience of really pushing yourself and suffering or applying yourself and you do it within a team context, within a context of people, you get that bond. You get that oxytocin; you get that serotonin.

The product isn’t something that we market. What we try to market more than anything is the fact that there’s a community aspect of it. And in certain markets where we have more of a presence, so in London where we have a thousand people that are in our cycling club, there’s a real community.

Places that are more international that aren’t necessarily metro hubs, not so much. For me, it is kind of helping transform people’s lives and adding value to their riding. Product to me is…

Eugene: Which is the end of the road. It’s kind of like the cherry on top in a way. It does create a sense of entry into the community.

Alex: Yeah, but you don’t have to wear Rapha to be a part of the community. For me, product is what I’m passionate about, but it’s not creating a new colorway for the sake of a new colorway or, you know, a product that does the same thing as another product in the range.

It’s about how can we push technology, how can we push fabrication, how can we push innovation to create no distractions in your cycling life? At the same time, how can we as a brand maybe transition from making loads of products to offering more services so our business model isn’t about taking resources. What can we do to just create experiences?

Eugene: Do you ever feel as though different points of your life you’ve had these existential sort of crises? Back to that point, like, what I thought was the right path is no longer the right path. Now you’re at a point where I’m curious if you see something else looming, because it seems like you’ve had these sort of definitive chapters that open up a new world.

Alex: That’s a really good question, because…

Eugene: Coming with the bangers today.

Alex: I expect nothing less. I’m getting to a point in my age where I feel a responsibility to use the network that I have or the platform to do something that’s not about me, to do something that is not about anything, but what’s going to help people.

I think that the key to our species—what makes us us when you take away all the consumer culture, when you take away all the social shit, when you take away all the economics—we are a species that is driven by dopamine, which is a survival instinct that says, “Stick. I need stick. Stick helps me hunt. Hunting is good, keeps me fed.”

We’re driven by oxytocin which is love that’s bonds, we’re driven by serotonin which is mood and we’re driven by endorphins. So when you accomplish something that you’ve applied yourself to you get this kind of amazing reward.

So what can I do to help engage those vital chemicals in our body in a different way than how Instagram is doing it? Because Instagram has glued us and other media outlets have glued us to our phones. They’ve glued us to consuming entertainment or consuming products.

Cycling, running, anything that’s outdoors, but particular cycling, it gives you all of that plus. And so the more that I could do to help people get into the sport, the more that I could do to bring the barriers down, the more that I could do to innovate and push technology and create a platform that makes it easy for people to put down their phones and do something that is positive for themselves.

Then that’s the journey I want to take. But at the same time, when I think about how the world is producing products I think automation has a big lever to play in this. I don’t mean machines sewing things, but biochemistry is going to get there where we are able to create yarns in the lab that are organic, that are cotton.

I don’t know where this journey will take me, but that’s kind of where my mind’s at. It’s important to question everything that you know; it’s important to look at where you want to be five years from now and figure out the path of how to get there.

Eugene: We returned to the topic of power and pricing. Pricing is the most immediate way to alienate or welcome certain people into the conversation, but there’s one undeniable reality. Price allows the opportunity to create groundbreaking and innovative creations.

Alex: I think what you get from cycling is way too important to not try to share it with people who maybe don’t know about it or who are just curious about it. It’s just too important. It’s so transformational. I don’t think the budget thing can ever happen, because it’s really difficult to achieve performance and innovation on a budget.

Eugene: Got it. So you think there’s a level of validation and attention that is created by doing things of a really high level.

Alex: Yeah, it’s doing the best work of your life. The best work of your life doesn’t start with a spreadsheet and a margin percentage. The best work of your life starts with what’s going to impact the community in the most positive way.

That usually starts with events; that usually starts with rides; that usually starts with, “Can we transform the sport?” Then, “Can we inspire people?” Can we inspire people to reach a certain destination, a certain goal in their life, a certain platitude, and then can we give them the tools that they need to reach that goal.

And so Rapha, I think, is polarizing to some people because of the price, to some people because of the art direction, to some people because of the community, to some people because we have all kinds of people ride with us—people that are professional athletes and people that are just starting out.

Eugene: You’re probably not oblivious to any of these. At the end of the day, acknowledgment is one thing, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that something’s wrong; it’s just that someone’s perspective is challenging you on how you do something.

Alex: And we’re super transparent. I read all the comments on Instagram and other things just because I’m curious what the temperature is from people’s perspectives. Some of them are just assumptions.

There’s a lot of assumptions out there. Everything gets taken with a grain of salt, because we’re really confident in what we’re doing. We’re doing things for the right reason and we’re putting our community in front of profits. I could definitely tell you that.

Eugene: Yeah. So how do you see Rapha, as someone who has a deeper mission that just so happens to be within the world of cycling—is there any way that can be exported, not in a negative sense, but taking that sort of mission and goal and applying it to different verticals? Was there ever an interest in applying yourself outside of cycling? Or maybe you personally? Let’s not use this brand; it’s you yourself.

Alex: Rapha is about road cycling and that’s where the passion is and if Rapha did something else it would be inauthentic. Do you know what I mean? It is about that camaraderie that you have with a friend. Doing running isn’t something that binds this team, this group, and this company together.

But me personally, I think the notion of creation, that’s the stuff that I’m super passionate about. I think people that are maybe 16 to 21, especially in the States, don’t have a service or a platform or education system that inspires them to go and become creators, whatever that might be: photography, art, product, even fashion, film. I think it’s because there is this fear, “I’m not good enough. I’m not a creative.” But it’s like anything; you need to practice, practice, practice.

So for me, this notion of creating without fear is something that is missing in this world. I feel like maybe that’s something that I can work with people to contribute on a scale, something that will impact and something that will create a generation of critical thinkers, so we’re not in the kind of mess that we are in today.

Eugene: Beyond all this, these are extremely lofty goals that arguably can persist beyond your time on this planet, to get super deep. How do you approach the deconstruction of these problems to make them more manageable?

So you’re not staring at a mountain every single day you wake up and you know that, “Hey, the reason why I’m interested in making this impact is because of…” I guess the easy way to say it is why are you inspired to do this?

Alex: Because we have a short time here and what better thing to do with your life than to try to create positive change.

But I think you go through a transformative process in yourself when you stop thinking about yourself and you start thinking about all the people that you meet that could have benefited from the opportunities that you’ve been fortunate enough to have.

You know there’s been plenty of people in my life that have inspired me, that continue to inspire me, that continue to to mentor me, that push me to be the best version of myself.

And I feel really lucky and I don’t know if everyone has that in their life. So it’s benefitted me tremendously having those people in my life. So what kind of platform can I create so everyone has access to that, so everyone has the ability to have that education that’s not taught by any school that’s only taught by experience, something that people get grandfathered in, that a Masterclass online is not going to teach you.

I mean it might, but I’ve taken some of those Masterclasses. I think the encouragement isn’t necessarily there. I think that’s what people are missing, that’s why people are stuck in social media.

Eugene: As we rounded off the conversation I asked Alex what are the things that get him personally excited and push him to continue his path. What’s evident is that there are some people that are setting out to create multigenerational goals and produce long lasting contributions that will outlive their time on this Earth.

Alex: The last thing that got me genuinely excited is something that I’ve been working on for two years, which is having a platform to teach people how to design. I will hopefully roll that out later this year, which will be widespread.

Also, working with Norman Foster and that’s been really special, because this guy’s a design legend, a living legend, someone that is 82-years-old that still competes in marathons. That is the ultimate goal of aspirational human being that is super kind and and really driven to push technology so all of humanity can benefit.

He’s someone that’s created new…I don’t want to say buildings because it’s more than that, but he’s someone that’s creating new spaces that’s changed social behaviors and work habits that’s led to creativity and innovation a thousand times over.

I think it’s when you work with architects you really start seeing what their lofty goals are. So how can you yourself have loftier goals? Then how can the next generation have loftier-er goals? And so it begins, right, because that is the journey of human progression.

Eugene: Alex’s path has taken him through several different channels. He’s clearly opened up to provide a conduit for the next generation, but not without a healthy dose of realism. There’s a certain struggle that we often overlook and especially so in an age where our best foot is often put forward with the memories we share.

There’s a sense of the luck that perhaps got Alex’s HomeRoom hoodie onto Kanye West, but where he is today was conceived with a hearty appetite for struggle, sacrifice, and discomfort.

Alex: I had no expectations of what it would be like. I just wanted to make stuff, make things, make objects, solve problems, create experiences. The reality is that it’s hard work. The thing of celebrity designers or superstar designers, that’s just never going to happen again.

You have to put in the time, you have to learn the craft, you have to learn skills, you have to get the respect of your peers. You have to suffer. You really do. And you have to fail a hundred thousand, 2,000, 4,000, 5,000 times.

I think it’s super important to be given enough leash to fail. As long as you’re not failing on purpose, it’s okay. And the reality of it is that it’s a somber state, because you’re constantly trying to express what hasn’t been expressed or you’re trying to seek something that hasn’t been expressed or you’re trying to innovate something that hasn’t been innovated and therefore there is no path.

The easy way is just to go and remake stuff that’s already been created and take two things, cut them up, and put them together and make one new thing. That’s really boring. That’s just kind of about having a moment of it being cool for a second. It’s not a lasting object. Think about the person who invented the first helmet or the person that invented the first running shoe or you think about the person that invented the combustible motor.

Someone invented the microphone or someone invented EVA or someone invented a jacquard machine or someone invented a Stoll knitting machine. Those are real innovations that last over time, because they solve a problem and if you’re not a problem solver you’re going to really struggle. Because it’s not about creating vanity and just art, not to be super discouraging, but that’s been my experience.