Luna Ikuta has a penchant for experimentation and exploration. A strong internal curiosity has pushed her to understand the process and materials with great artistic effect. During her time at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), she took full advantage of the well-resourced facilities at her school—often in direct opposition to her assigned work—allowed her to experiment and develop an intimate understanding of a variety of materials.

As her beginnings in industrial design carried over into fine art, her strong command of the materials and fabrication side of art helped her to assist other artists to translate visions into tangible objects.

From fast-curing chemical resin meditatively molded within an hour to traditional Japanese paper objects reimagined in black patina iron, her works explore the connection between a material’s essential properties and their emotional impact on the viewer.

Luna: My name is Luna Ikuta and I’m an artist and designer living in Los Angeles. I graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. I was born in Japan and then moved to the States when I was super young and now work primarily in sculpting with resin casting and metals.

Nate: Was art always a part of your early childhood?

Luna: I didn’t go to art high school. I applied mainly to engineering and architecture programs and RISD was only art school I applied to, but yeah, I graduated there with an industrial design degree and transitioned into fine art coming out of it.

Nate: I’m curious what led you to go for engineering originally?

Luna: Maybe growing up in a Japanese household? I was always going to “after-school school” when I was younger. In Japan, people go to Kumon and so I would always go there to study calculus, math, and engineering. I thought I wanted to go into that particular field only because I was good at it. And then I took this architecture course back in my summer of junior year and then fell in love with a hybrid of engineering and art. That’s why I took my chances and applied to RISD. The program was kind of a hybrid, along the lines of industrial design, but different than architecture. So I thought I was going to be an architect but then transitioned more into ID (industrial design) because ID has a lot more courses with hands-on building and that’s what I fell in love with.

Nate: I’m not sure how the process goes, but I guess you develop a portfolio as you go. Did you start as an independent or do you kind of cut your teeth at different firms?

Luna: All the opportunities I received post-college were from experiences that I had during the summers at being in college. Just to backtrack, I would intern at a lot of artist design studios when I was at RISD during the summers and got that hands-on experience of what it felt like to be an artist in a studio, where it’s your full-time job. And even though I was in industrial design, I was more interested in fine art from the beginning. All the internships I chose were more hands-on with these artists studios who were represented by galleries or where I helped them create their work for their gallery shows.

Nate: So it was easy to transition out of school?

Luna: Having those experiences definitely made it be easier to branch out into other firms. The first job I had was a fabrication assistant at this design studio called Ball-Nogues where they do a lot of public art installations. And that was a really good experience just learning how these large-scale pieces are built. At school they don’t actually teach you how to really take an idea to full-on huge scale projects like in a public realm. Being in that studio, I was able to see how everything worked from the ground up. I was there for a year and then I decided to go back into the design realm and focus on custom furniture for hospitality. There, I was doing a lot of custom lighting, furniture, and all kinds of interior aspects under the term FF&E (furniture, fixtures and equipment) for a lot of restaurants in L.A., New York and London. I recently just left that to venture off on my own.

Nate: One thing that seems to permeate your work is this sense of shokunin heritage, is that something you grew up with?

Luna: Yeah, I would say so. I have a lot of respect for it and I think nowadays especially coming from that industrial design world, I know how easy it is to make anything. A lot of times you can send things out to a factory and with technology in itself, you can make whatever you want. But I also think that the appreciation for mastery in craft is something that will never die, nor should it die. Artists that I do respect and look up to a lot, are people that definitely have these years of experience that allow them to know exactly what to do. They’re not afraid of getting dirty in the process and knowing how to make something with the body and with their hands. It gives a bit more depth to me, not to say that everything has to be made by hand. It’s good to know what you’re working with when you are presenting material and taking that on as your medium. I think it’s important to be able to speak its language in its entirety.

Nate: Absolutely and to come back to my previous example of the shokunin, becoming one is almost a whole lifetime. My experience is that it requires a lot of feeling it out and just lots of repetition until you have that sense, that instinct. But in your case, you also had a lot of talent for the technical aspect with your engineering. Do you think that’s giving you some kind of—I don’t wanna say advantages—but some unique traits that influence your work? Part of me feels like you’re ahead of the game because you feel it out, but you can calculate it as in, “I didn’t need to feel it out, but I could figure it out.”

Luna: Yeah, it’s helpful to intersect a design and fabrication background while also being familiar with 3D technology and vendor relations. I used RISD as a lab for material research. That has prepped me a lot for just being able to have an inherent understanding of what this material is going to do. A lot of my work now is pushing how these materials can be used in, maybe not so much in a product-oriented or practical purpose, but how these materials affect our feelings and mood. I’m actually really interested in knowing how these objects and everyday materials affect our daily emotions. We are so accustomed to seeing them and the way they are, but what happens when you play around with the weight of a cup or the texture of a certain table? I’m really interested in the properties of a material in itself and how artists use that as an emotional language.

“With resin, I have about an hour to work with this certain mass that I’m forming with my hands. But if I do too much, then it cures without actually being formed. If I do too little, that’s kind of this waste of time. It’s finding the right balance within that hour or so and I can do nothing but that. And so that practice has been in a way very therapeutic.”

Nate: That totally makes sense. This is really basic, but I used to say, poke around with 3D modeling and you could change texture and patterns. Not to say you could make say, a cup covered in fur or whatever, but it does change our perceptions of what object should be made out of. So when you’re seen playing with the weight, which I’ve seen pop up a lot in reference to your work, could you give an example where you’ve explored the materials and their relationship to weight?

Luna: I did an entire project based around the concept of weight using these Daruma dolls. For anyone who’s not familiar with Daruma dolls, they’re traditional household items that you see in Japanese homes, restaurants, bars and they’re regarded as good luck. It stems from Bodhidharma and Buddhism and through Dharma, it’s how the name Daruma came to be. So the Daruma is something that Japanese people don’t even look twice at anymore. It’s so common. When you first receive it, you mark the left eye when you make a wish and mark the right eye when it comes true. I found that object really beautiful in itself and the fact that it’s designed to house ambition and goals. Regardless or not if you believe my spirituality, I think that sentiment in itself is very positive and affects our mentality and how we achieve those goals. Because I grew up with these but I also grew up in the States, these dolls are just so fascinating. I see them all over in Japan. But they’re kind of trinkets in the States. When you pick up a daruma, it’s typically made out of papier mâché and really light. I just thought that there was a disconnect between the actual weight of the object to the purpose in which you know we embalm our goals into—it should be something that has a bit more impact, a substance when we hold it in our hands.

Nate: How did you reappropriate it?

Luna: I took that object, designed my own shape and face for it and cast it in iron and painted it all black to emphasize the weight of the object and how it can parallel its purpose for the weight of our emotions. I thought about changing something traditional in a sense that no one would ever think. When I brought those over to Japan and to my family members, they said “I never even thought about the weight of this, but it makes sense!”

Nate: It does! And I noticed, I always saw it from from the Instagram photos and I don’t know what type of iron, but it still had its texture.

Luna: Yeah, those are sandcast so it still has that industrial texture to it.

Nate: It’s something spiritual. It feels like it could have been at home in a place of spiritual significance. It’s not been polished.

Luna: Right and iron itself, it’s from the earth and from the ground. So there’s something about using iron and not making it out of silver or bronze or anything like that. That’s the large part of what makes up the earth into this more spiritual object—it just felt like they had the right connection with these two to three-inch objects, but which weigh about three pounds.

Nate: Whoa, it’s dense.

Luna: It’s really dense, it’s full-on iron and pretty heavy!

Nate: How do you see the current process of trends in design and maybe specifically restaurant examples you’ve seen? The reason why I brought that up was that I’m just noticing—like you said when you have access to something: for a maker trying to experiment and just try new things, that’s great. But when there’s a company with a sizable amount of resources, they can potentially make that big and trendy and then everybody wants to do it. And before you know it, our world has been reshaped because of these objects coming in.

Luna: Right, which I think that’s a bit sad to see. On the other hand, it’s great that we do have the resources with social media with everyone being so well connected, it’s easy for all of us to access these new trends or designs or products. I think there are trends in very different pockets. For me, the trend I can speak about most is interiors for me because I was working in hospitality for a while and designing furniture, objects lighting, and even artworks for restaurants. There’s not that much longevity in a lot of it. And I think it gets a bit confusing when people don’t really know what’s quality versus what’s in right now. The turnaround of what is in right now is so fast, it gets a little depressing just to see like, “oh, that was so cool last week.” It was on everyone’s sponsored feed for a minute. I think maybe in a backward way, people are getting better at judging what’s good and bad too because there’s so much that everyone’s forced to choose to an extent.

Nate: How do you personally want to impact this movement?

Luna: People might not really care how it’s made. Which is why again I really respect going back into the master of craft and mastery of the material that can really work in. Even in the garment industry, we don’t know how it’s made, but a lot of the time it’s unethical. I think people are more aware of it. The more it’s out there, the more people are looking at, “oh, how is it made?” Because we see it in conversation a lot more. Having the appreciation of the human aspect of how every object is designed is important for everyone to be aware of. It makes people more appreciative of the things that they do own.

Nate: Absolutely. Are there any other materials you’re interested in exploring?

Luna: I guess transitioning away from design stuff that I’ve been talking about, I’ve been really interested in with resin.

Nate: I noticed!

Luna: I think resin is fascinating because it’s difficult to use, it has just very temperamental properties to it. It’s tedious and it smells bad! There’s a lot of artists in the light and space movement that I really respect, like Peter Alexander. And you know there’s something about resin to me that I like a lot because of the way it can be manipulated in a lot of different ways and it also has a time limitation to it. It cures within 45 minutes or an hour. I’m also using resins that are able to be sculpted and so that goes into the process of working with my hands. Getting familiar with the language of this material and what it does and doesn’t want to do. I actually discovered it back in college where I was making molds for casting in metal. You would sculpt with it and you would create this form and it would harden into this plastic piece over time, unlike clay, where I would touch it and it would mess up. I would be done with it. I just let it sit for an hour and then it would fully cure.

Nate: Could you tell me a bit about your recent resin work in particular?

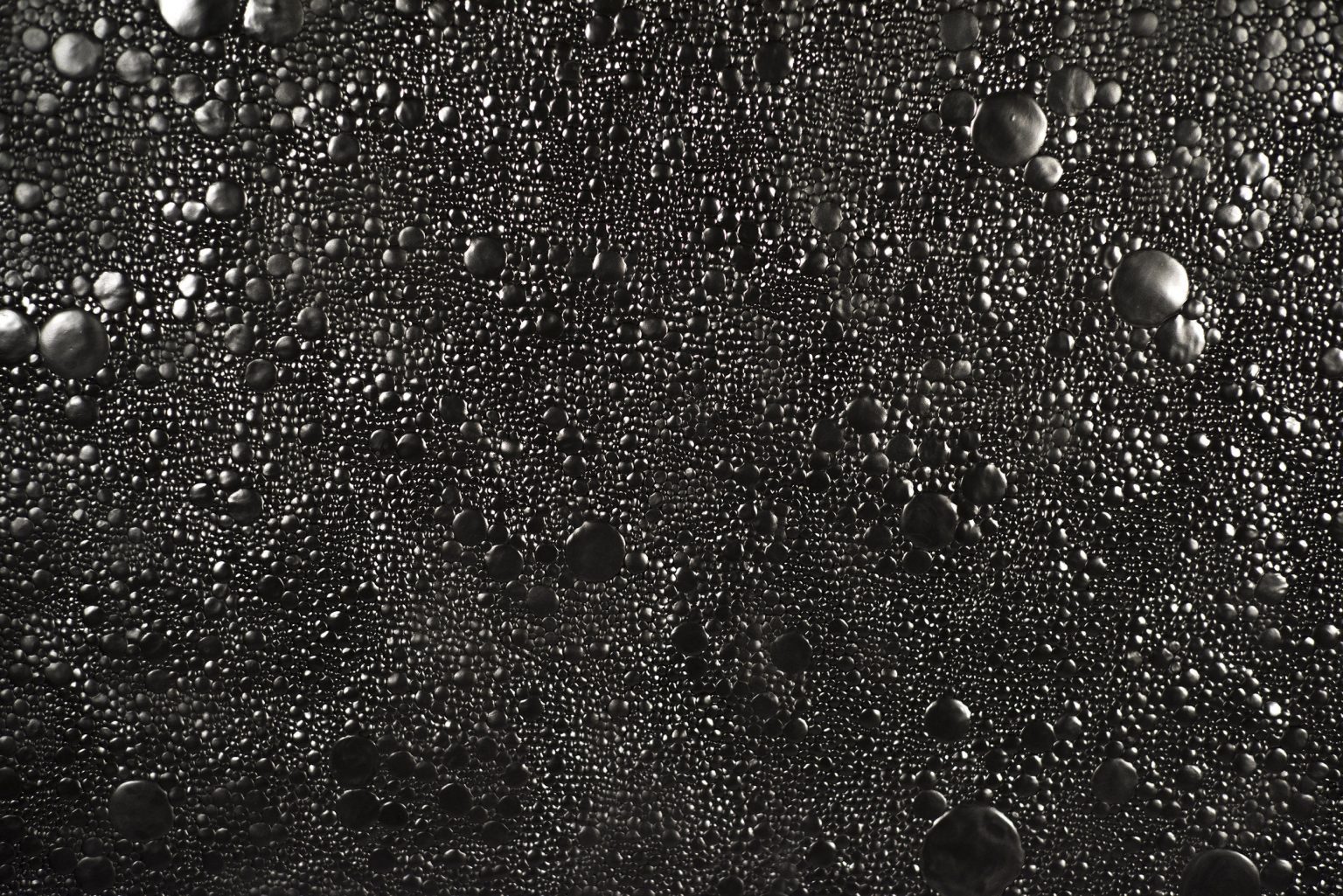

Luna: So these works are primarily large 48-inch or so scaled panels of resin sculptures and I’m calling “phases,” but they’re essentially textured pieces that to me first started by trying to find a way to find my silence. These sculptures really started because I was working a lot in the design world and figuring out all these deadlines and everything was really loud and cluttered around me. I began working with this clay-like material, just kneading and forming it and placing it onto this canvas. That brought the repetitive motions and the physicality behind it. It introduced a pure form of silence in my mind. And that was my form of meditation. It became very necessary for me to do after a while—just find that state of calm, that state of silence. These pieces are large landscapes that seem like a randomized order and placement in texture. But in reality, it has this constrained shape and limitation in the working time of the material. It really forces me to be present. And so for me, the process is what really drives these pieces and they’re not necessarily representative of an abstract form, but it’s more of kind of appreciation and dedication to that form of meditation.

Nate: Totally, because you have that limited working time and then that’s it, it’s frozen in time after.

Luna: With resin, I have about an hour to work with this certain mass that I’m forming with my hands. But if I do too much, then it cures without actually being formed. If I do too little, that’s kind of this waste of time. It’s finding the right balance within that hour or so and I can do nothing but that. And so that practice has been in a way very therapeutic.

Nate: I’m viewing these in kind of performative aspect too.

Luna: Yeah! It’s a set, I call them sets also.

Nate: Yeah, “I’m just starting my set and I’ve only got an hour.” And like you said, you have to be so many things: you have to be economical with your time, but you’re still trying to fulfill something. That’s so challenging.

Luna: Yeah. It really started because of a necessity of just, there’s so much noise throughout the day. I mean, it was cell phones, I’m in L.A., it’s traffic. Just all this background shit that’s constantly making us feel very anxious. And so for me, physical meditation wasn’t really doing it. Reading a book, my mind was going wandering a bunch of places and so these pieces started with just this material in itself spoke to me and in a way it helped me find this in Japanese, we call it ‘mu‘ it is just nothingness. And that mental space became necessary in my daily life to keep me grounded into myself.

“I definitely prefer the micro-projects—the fewer voices you have to channel through. It’s always more true to your intentions. It’s kind of how I envision it and its execution is on you. If it’s not up to spec, it’s my doing, my fault or my lack of knowledge.”

Nate: I understand you don’t just do one discipline. How do you spend your time between artist work and contract work?

Luna: So right now I’m independent. I’m also contracted for some fabrication work and I do my own work for my own commissions. I’m also helping out other studios and artists figures on how to build their projects and assisting a lot from the fabrication side. If an artist or painter doesn’t know how to make a sculpture, for example, then l assist in and figuring out the 3D aspect of it and how to speak to vendors in that language.

Nate: Are you sort of a missing link? Artists might have the artistic vision and the imagination but when it comes down to turning that idea into something physical, that’s where the challenge begins. Is that something that’s pretty common?

Luna: Yeah, it is actually pretty common where an artist doesn’t actually know how to physically make that piece that they’re envisioning. It doesn’t make them any less creative or any less talented. But I think having a fluent language in knowing how to build something is quite rare and something that people have to be really interested to learn. It’s actually interesting. A lot of times people will ask, “oh yeah, this person needs help building this,” and I’m a bit surprised.

“…for me, physical meditation wasn’t really doing it. Reading a book, my mind was going wandering a bunch of places and so these pieces started with just this material in itself spoke to me and in a way it helped me find this in Japanese, we call it ‘mu’ it is just nothingness. And that mental space became necessary in my daily life to keep me backgrounded into myself.”

Nate: Would you say that the traditional divide that separated the arts and the sciences is dissolving now?

Luna: Yeah definitely I think so. Because of the rise of technology and because we’re all able to actually fabricate these ideas, these artists you know are not physically making them themselves. They’re able to create these amazing crazy installations that are essentially designed by engineering. And so I think both of them definitely do go hand-in-hand more-so than they used to before. Because of the merging of those two worlds, we’re able to see so many amazing sculptures of giant scale. Even in sculpture, you still need to quantify mass and everything is still related to the weight behind things or whether or not this hanging sculpture is going to support itself. All those factors are considered when creating public-scale pieces. Most of the time these projects have to be accomplished by the help of vendors and fabricators and a lot of hands-on deck to create them at that scale. Even looking at fashion shows now, you have these amazing sets that are a piece of art in itself.

Nate: Having done large multi-vendor operations and smaller operations, which do you prefer?

Luna: I definitely prefer the micro projects—the fewer voices you have to channel through. It’s always more true to your intentions. It’s kind of how I envision it and its execution is on you. If it’s not up to spec, it’s my doing, my fault or my lack of knowledge. There’s also more time and not as many people giving you that pressure, but when you do work in a more macro scale it’s obviously satisfying in a different sense.

“A lot of my work now is pushing how these materials can be used in, maybe not so much of a product-oriented or practical purpose, but how these materials actually affect how we feel.”