Not so long ago, there was a clear divide between the digitally connected and the unconnected. That’s no longer the case. So what does that mean for our experiences now?

The view from El Malecón, a six-mile stretch of cliffs in Lima’s Miraflores area.

The Jorge Chávez International Airport is Peru’s main international and domestic airport.

“Man, what’s that smell?”

This is the first thing that crosses my mind the minute those sliding doors open at Lima’s Jorge Chávez International Airport. The ratio of garbage and fish may change with the location, and the intensity with the day’s winds. The odor might be an unpleasant welcome, but it becomes a distant memory once I get lost in Peru’s vast landscape and rich culture.

The unhindered access to information has made the relatively casual traveler much more capable than one pre-Internet era. Having said that, the stress and mental calculations that accompany curating the perfect experience can be an unnecessary burden. The surprises of travel, unspoiled by mentally noting a restaurant rating or a comment left on a blog post, provide a much more objective and authentic experience, if you’re equally ok with the surprise of a great meal alongside a mediocre and terrible one.

The traveling I do now entails going in blind when possible and doing minimal research on the ground. My earliest experiences with Peru revolved around their football kit, defined by a bold diagonal red stripe across the chest. This kit combined with grainy footage of FIFA 100 and Peru’s greatest player ever, Teófilo Cubillas, left a pleasant memory in my mind as a kid. Later on, it was the Peruvian-inspired cuisine of Nobu that made me curious about one of the original fusion foods that married Asian and South American flavors.

Peru’s rich past at the heart of the Incan Empire and its colonization at the hands of the Spanish Empire are a not-so-distant part of the country’s history. The world’s globalization has afforded Peru more than a number of modern amenities. The most powerful and omnipresent one, Internet access, is speedy with a couple GBs of 4G data available for a few dollars. Meanwhile, an Uber ride from the airport to most places is cheaper than the starting fare of a Manhattan cab.

This unprecedented convenience casts a shadow over my head. There’s almost too much familiarity while traveling given the fact that I’m thousands of kilometers away from home. It starts to feel as though most big cities, which in my situation means Lima, will grow increasingly similar to other cities across the globe.

Cusco

A view half-way up the hill within the city limits of Cusco.

After a few days in Lima, my wife Nicole and I head away from the coast and towards the city of Cusco. The city is among the world’s oldest, dating back to 1100. It is near the Urubamba Valley in the Andes mountain range, which means speaking of Cusco usually comes with a warning to travellers to be cautious of the high elevation. Cocoa leaves are available everywhere as they serve as the first counter against altitude sickness. They’re a welcome sight when walking at a brisk pace or traversing some of the hilly terrain.

The small airport is rife with Ubers. In record time (literally one minute), we’re off to our Airbnb. The availability of these modern conveniences is once again not lost on us, but it’s still shocking to see how these global companies have established themselves so seamlessly around the world. The neighborhoods surrounding the tiny Cusco airport pale in comparison to the rolling hills of the main part of town, the part that has come to represent Peru’s most important tourist area. But for many, Cusco is still just another stop.

Reaching Machu Picchu is the goal most travelers in Cusco are seeking to accomplish. It’s a commitment. Call time is 4 AM and since I’m part of a tour, there’s pressure to not be that person that delays a bus full of 40-some people from visiting the 15th-century Incan citadel. The multi-leg journey includes a bus, a train, and a second bus. The first leg by bus is largely unremarkable, there’s nothing to really see, because naturally the sun has yet to rise.

Train to Machu Picchu

The journey starts to be memorable on the train. Large windows and skylights provide a good survey of our surroundings and there’s good service from the hosts and hostesses as we make our way to the base of Machu Picchu. At the base is the small town of Aguas Calientes, which has since shed its name in favor of the more practical “Machu Picchu Town.” It is like any other touristy town that serves as a checkpoint before the main event, and lacks any attractions of its own.

The final ascent up to Machu Picchu by bus can honestly be pretty harrowing. The narrow roads lack guardrails, not that they would be all that useful in the event that a large tourist bus careened into one. Along this undeveloped and bumpy road are views that remind me why I woke up before dawn.

The efficiency of a well-oiled tourist machine becomes clear as I step off the bus. The soft dirt is muddy from seasonal rains and I keep an eye on the ground to avoid losing a shoe.

Machu Picchu

Large tourist groups surround the entrance. There’s a constant stream of Spanish coming from this crowd and a cacophony of global languages; although Mandarin is absent, which is a bit of a surprise. The high cost of travel, the time commitment, and the challenge of getting a visa to enter the country all add up to be deterrents to casual travellers.

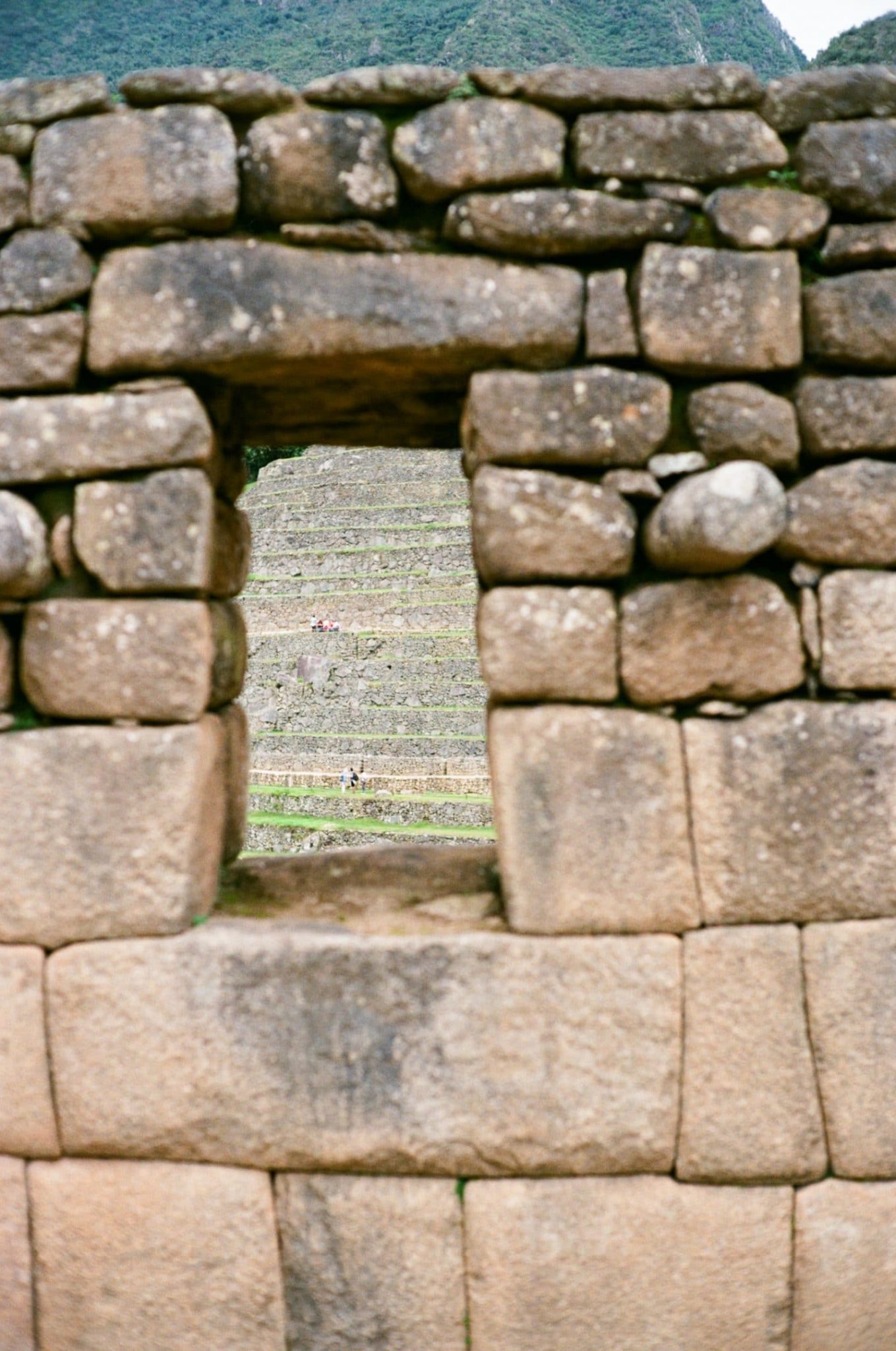

In front of the entrance to the site is a series of gates with small engravings. For 339 years, Machu Picchu lay dormant after the Incans abandoned it. It’s seen as a celebration that it was “rediscovered” by American explorer, Hiram Bingham. Paying homage to Bingham seems odd, as the focus then shifts from the Incan culture that built Machu Picchu towards the person who shared it with the rest of the world. The run-up to the first vantage point is nevertheless exciting.

Even a small amount of searching will result in picturesque postcard-like images of Machu Picchu, but that simple visual fulfilment is completely different from being physically there. The cool breeze in the shade, the smell of the diverse foliage, and an unobstructed 360-degree view remind me of what it means to actually be present. No amount of Wikipedia reading or Instagram scrolling can adequately substitute this experience. Yet, the decision to be present is not without friction. I’m unwillingly thrust into a shared world of fellow social media users who are waiting at selective points to take their photos. Bottlenecks form and my fellow travellers’ curatorial decisions directly affect my experience.

Nicole and I spot a couple soon after we start walking around. The man has his arm extended and is spinning around. It appears he’s Facetiming with their family back in India. I sneak a look at my phone and am astonished. Three bars of LTE connection.

As much as we collectively remind each other to seek downtime in a connected world to rest our distracted minds—to catch a “mental breather”—it’s clear that sometimes greater lengths are necessary to achieve it. On the one hand, I can’t help but be excited for countries like Peru to leap frog all the developmental time and effort spent on getting us to where we are today. Everyone can now enjoy the emergence of their country on a global stage with a highly capable smartphone and the world at their fingertips.

On the other hand, the powerful human desire for convenience is affecting not just select generations or groups of people, but humanity as a whole. Convenience of connection, convenience of travel, and convenience of accommodation simultaneously contribute to economic growth and alter the individual traveller’s journey. When people ask me about my trip to Machu Picchu, my default answer is simply, “it was a trek to get there,” because that response seems to meet their expectations. The truth is that it wasn’t a trek, but the increasingly antiquated perception that spending time and effort is an important part of creating valuable memories persists.