Matt Abergel, Lindsay Jang and the rest of the crew at Yardbird didn’t know where they’d end up when they first opened the doors to their modern izakaya-style restaurant. It’s five years later and on the day of their anniversary, they discuss some of the struggles they faced at the beginning and what it takes to sustain a restaurant in a city where rents are high, customers are picky and there are just too many light bulbs to choose from.

“I think the first week into Yardbird we had four kitchen staff, and we started with maybe eight staff. In the morning we were cutting 10 to 15 chickens a day and just trying to figure out what the fuck we were doing?”

— Matt Abergel, Co-Founder of Yardbird

A glimpse into the Yardbird kitchen.

Comments like these are to be expected when your restaurant opens its doors for the first time, even coming from Matt Abergel and his business partner Lindsay Jang, both of whom already have extensive experience under their belt. Matt’s an accomplished chef who has worked across the globe including under the world-renowned Masayoshi Takayama and his New York-based restaurant Masa. Likewise, steeped in a proud tradition of Japanese cuisine, Lindsay Jang served for many years as the linchpin at Nobu.

You could say a New York and a Hong Kong minute both run on the same clockwork and their experiences stateside as well as in London certainly allowed them to hit the ground running when they settled in the Asian metropolis. Yardbird’s ability to keep up with the city’s frenetic pace, all while dancing to its own beat, has earned it both local and international acclaim.

A typical night, any day of the week is brimming with atmosphere, with tables packed with tipsy patrons, massive bottles of sake filling up rows of glasses, and the aroma of their modern interpretations of izakaya food such as corn tempura, Korean fried cauliflower, and of course, skewers of painstakingly-prepared chicken. With chicken as their signature, their mastery extends well beyond the typical fare of thigh and breast meat to include the tails, knees, and even hearts.

Yet, after the excitement of the first few months wear off, and the initial (rave) reviews pass, few initially successful restaurants can claim consistent results over such a period, much less continued growth down the line. Five years later and still going strong, Yardbird is clearly doing something right, yet without compromising its direction. For Matt, it was about starting small and simple with modest goals, where at most sixty or so people would come in for some yakitori. And for Lindsay, it was about sticking to the original plan even as the business went further down the line. “Down to the details, the food, the people, the music, the staff. It’s pretty awesome that our business plan from 2008 is still our business plan in 2016.”

If there was a secret recipe to success, Matt, Lindsay, and the rest of the Yardbird team just might have found it. We spoke with several of them over the course of several days both before service and during the evening of their 5th anniversary.

Tara Babins (Left) and Matt Abergel (Right) of Yardbird.

Lindsay Jang, co-owner of Yardbird, records her audio interview.

The Yardbird wordmark logo was designed by Evan Hecox.

Unlikely Origins

It goes without saying that the popularity of more casual foods like Izakaya staples such as yakitori and kushiyaki, along with ramen, have easily stolen some of the exclusive spotlights that sushi once enjoyed with Japanese food aficionados. And this is particularly true in Hong Kong, where restaurants specializing in these items are becoming as common as they would be in any Japanese city.

The restaurant industry in Asia’s “world city” is already one of the most active and exciting, yet it’s particularly unforgiving and extremely critical. With some of the world’s highest property prices and the unabashed home of a fast and fickle consumer base always eager to move on from one thing to the latest and greatest, it’s not uncommon to eat at a restaurant only to find it replaced only six months later.

So how do you lay the groundwork for such a successful yet staunchly authentic business in one of the harshest of climates? For Matt and Lindsay, it started with pure entrepreneurial gumption and a small business mindset, one that began in the most unexpected of places.

Matt recounts his and Lindsay’s humble origins on the comparatively desolate prairies of western Canada. Both worked together there at The Source, a skate shop in Calgary, while Lindsay’s father also owned a Chinese restaurant in Sherwood Park. “The people that owned the skate shops would just give us so much freedom as kids to run their business,” he says. “We do the same thing. The heart of the business is these young, energetic people who want to have fun.”

Since its inception, Yardbird continued this tradition of running their business on their terms, introducing at the time uncommon Hong Kong practices including tip-free bills and the most glaring, no reservations. While these didn’t immediately make Yardbird a fan favorite, they did show their knack for committing to deeply-held principles, something Matt is glad he did. Amid the sea of trends and nit-picky patrons that are Hong Kong, the mentality of “businesses that were run by the people that started them,” ones that didn’t compromise and emphasized community, people, and fun; has followed him every step of the way.

“You have people who are building something within the city, that are taking the time, the energy, and the effort to enrich the city, as opposed to just working here just for a few years, getting paid very well and then leaving.”

— Kenneth Chan, Head of Operations at Yardbird

Service prep. A front-of-house staff member sets the tables in advance of service start.

Stacey Jang manages all of the Yardbird business operations and administration responsibilities.

Kaizen: Continual Growth

While the end experience for the customer is intended to be seamlessly enjoyable, accomplishing that takes a strong game plan that ensures any hiccups are resolved behind the scenes. The crew at Yardbird don’t openly communicate their commitment to the term Kaizen. But it’s wholly apparent. It’s a Japanese philosophy of improving efficiency and workflow, a central theme to the way Yardbird operates, with ever-changing procedures since its first year.

“My only job was to build the office. All I knew was that I had to buy the supplies,” recalls Office Manager and Lindsay’s sister Stacey Jang. “And I didn’t know how much was appropriate to spend.” For her, this new role and set of challenges would inevitably result in no shortage of odd experiences including panicking over fifty cents (in Hong Kong dollars, no less) of missing change out of petty cash and manually doing inventory for the first year with just a calculator.

Despite early shortcomings in their workflow, the spirit of continual improvement took hold once they figured out what one particular bottleneck was.

It was Matt.

In the formative years, he essentially called the shots in many decisions and often took far too long or held too much control: “I never was good at dealing with money,” he admits. “In the beginning, I literally tried to do everything myself.” This tendency to micromanage sometimes resulted in a gross loss of productivity: “Like picking a fucking light bulb, y’know, it took me three days to pick a light fixture.”

Despite an unbalanced distribution of the workload, the crew intuitively settled into roles, hustled and got things done. Eventually, things would turn around. “We started focusing on everybody’s strengths,” Stacey remembers. And most importantly, the team stopped focusing on what was holding them back.

With this epiphany, every member of the team was able to play to their strengths while proper management ensured everyone took on the right responsibilities. As they began delegating, Stacey would step in to fill gaps and pick up odd tasks to hold the team together. And Matt? “He could focus what he wanted to focus on: not buying light bulbs.”

While the learning curve for those first few years was steep, allowing the team members to specialize meant that the ongoing issues of deciding how to use somebody best soon evaporated.

Elliot Faber is the Yardbird, RONIN and Sunday’s Grocery Beverage Director.

People First

Productivity systems and the importance of running a tight ship aside, one of the key factors behind Yardbird’s success and that of any service-based business has been nurturing meaningful relationships. It’s the people running it, the ones supplying it and the ones walking through its doors, something that Beverage Director Elliot Faber, could not agree with more.

In his role, Elliot Faber’s mission isn’t just about mixing and slinging cocktails and having a good laugh with the clientele. It’s about leaving them buzzed and educated. When he speaks, there’s this clear desire to pass on his vast knowledge and experience with both colleague and customer alike. He’s always had a strong affinity for learning and training. “It’s about finding the story and why they make it,” he explains, referring to the lengthy process behind making some of the alcohol served at Yardbird. “It’s about taking all of those things and sharing that story, as I said with our guests, but as well with our staff.”

Elliot quickly points out the fact that he aims to educate his staff to the point where his role is no longer needed. He believes this earnest desire to share quality, beneficial, and relevant information goes a long way, especially in a food scene as discerning as Hong Kong’s: “A guest can smell bullshit a mile away. They know if you genuinely don’t like something. You can’t just point to the bottom of the list because it’s the most expensive item and say ‘that is the best.’ Because why is it the best?”

Instead of thinking purely in terms of numbers and reputation alone, Elliot strongly believes that authenticity has the greatest power to persuade. It’s the passion conveyed through your voice that acts as a starting point towards a great relationship of trust in the dining room. This interaction has both social and financial rewards through “repeat guests, higher check averages, and everything that goes along with it.”

While Elliot shares the passion fueling Yardbird through education, in particular, Head of Operations Kenneth Chan finds a sense of camaraderie and thoughtfulness is what holds the front of house together. This sense of ownership extends from the people that own and manage the space to the people that work in it.

And when these details matter, it means everyone goes the extra mile, not out of a sense of duty, but a sense of compassion and mastery. For instance, he says, “when you talk about a chopstick dropping and someone running as fast as they can to replace that for you, it’s because they care. They care about the guests’ experience. They care to do things to the best of their ability, as quick as possible and as efficient as possible.”

This same value system translates well into the kitchen, where busy kitchen staff like sous chef Paul Tsang get to prepare food in an atmosphere he deems relaxing. The front of house might argue that they’re never quite at ease with the energy and guests, but to Paul, Yardbird pales in comparisons to some of his previous experiences.

“Everybody’s free here, and we’re happy. That’s an important element,” he relates in Cantonese. While a kitchen operating at a blistering pace results in the “speedy but surly” service the city is known for, Paul emphasizes the importance of breathing room in producing better results: “Sometimes if you don’t have a lot of pressure, you can do a better job. You’re more engaged with each task, and you’re more passionate.”

Where the magic happens. Yardbird chefs pose in the kitchen.

Stacks of Yardbird’s Japanese plating.

Build It and They Will Come

Once you find your tempo, there’s that tiny bit of time and energy to take a step back and look at the bigger picture.

As luck would have it, Yardbird has been able to actualize its philosophy beyond just an enjoyable and memorable service experience that lasts the length of a guest’s stay. True, business is only successful so long as the people in the community that patronize it are happy. But oddly enough, when everything lines up with the appropriate timing, sometimes a business provides everybody with a community.

Anyone who’s lived in Hong Kong past the one-year mark can attest to a feeling of restlessness common in such a transient city, one that many from all over the world might endure as they struggle to call this place home. Kenneth confides that the hardest aspect of living in the densely-populated but detached city is the lack of belonging. “You don’t have your friends, you don’t have your family, you don’t have people that care about Hong Kong or the city.”

Without much to hang onto aside from their job and a few work friendships, some might linger for a few years, keeping their spirits up with a boom-bust cycle of grinding and partying only to eventually move on, having nothing positive to show for their time.

Still, it’s possible to find something deeper given the opportunity, as was the case with Kenneth, who was never expected to stay in Hong Kong for very long. For him, Yardbird became more than just a strong reason to remain in the city; it was a means to contribute.

“You have people who are building something within the city, that are taking the time, the energy, and the effort to enrich the city,” he says. “As opposed to just working here just for a few years, getting paid very well and then leaving.”

Hong Kong is undeniably a fast-moving city, but also one steeped in a long culinary history. This means there are plenty of chefs that are committed to working hard and taking their craft seriously. Paired with an establishment that respects their efforts, it’s a powerful combination, one that Matt sees in his kitchen: “Cantonese people have amazing work ethic, and it’s a big thing [for us] about taking care of them and paying them properly. I have seven or eight chefs that have been with me for seven years since the day I moved to Hong Kong. The loyalty is there.”

Beyond simply a sense of belonging, Yardbird’s five years of success hint at much more “community building” to come, in the literal sense. With Ronin, a Japanese whisky bar, and Sunday’s Grocery, a bodega concept being the most recent additions to the community, there’s talk every day about opening another Yardbird somewhere else in the world. The answer every time is a sharp “no.” and perhaps with good reason.

With every mention of another outlet comes worries about “watering down” the recipe. Matt’s response? He believes that when a business chooses to keep its authenticity rooted in the face-to-face interactions between people and in only one location no less, the term “selling out” just doesn’t apply. “In a restaurant, we touch every single person,” he says. “For me the brand is the product, the product is the brand.”

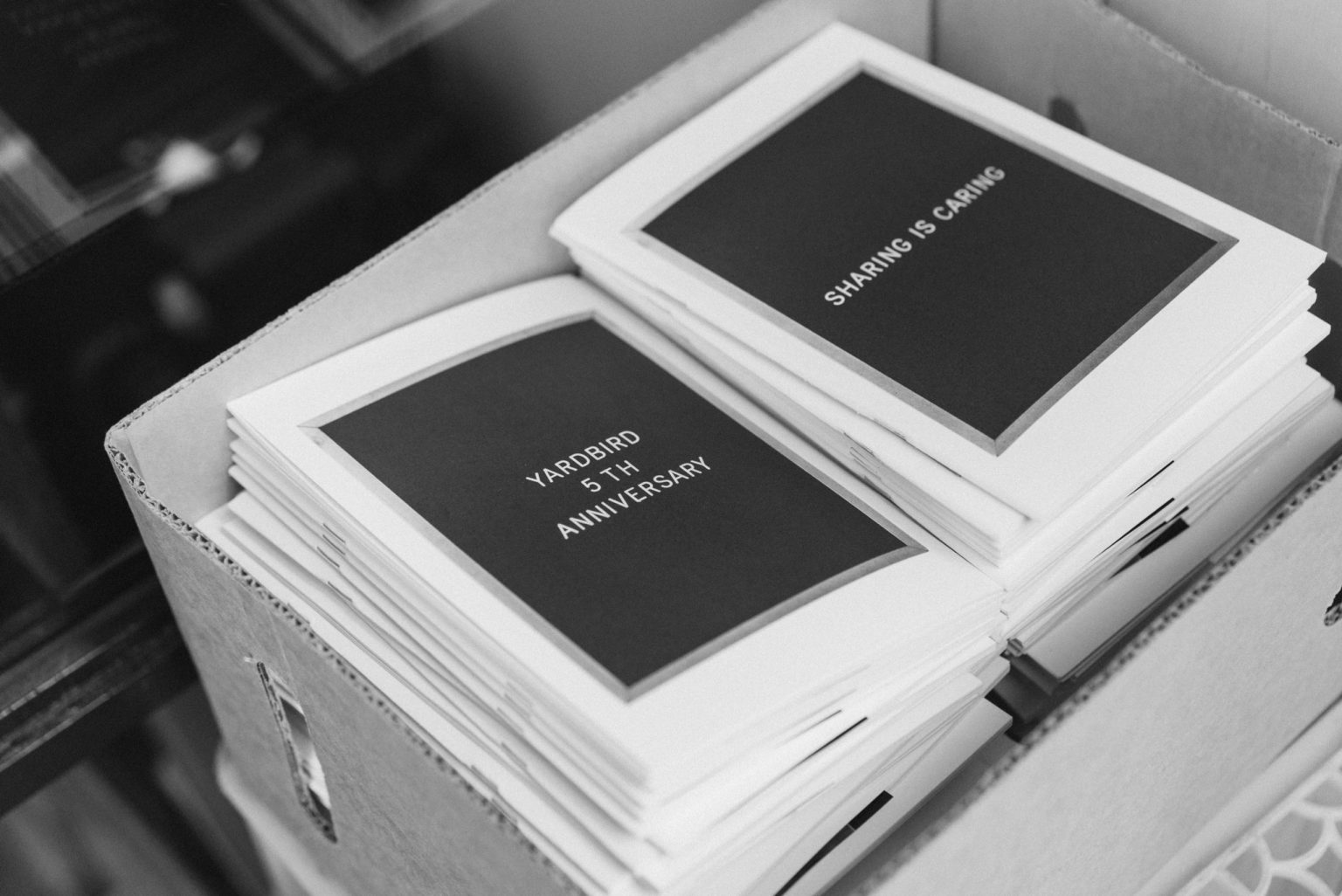

Yardbird’s 5-Year anniversary zine.