Picture this: a line of dozens of people snaking down the aisle of a convention center, each writing their names on a legal pad. No, they aren’t signing up for the chance to win a free trip to the Bahamas, or an Oculus Rift headset. They are entering a lottery for the chance to pay $65,000 for an edition of a new print by the artist KAWS.

This unlikely scene played out during the first hour of the VIP preview at Art Basel Miami Beach in December. And it is emblematic of the extraordinary ascent of an artist who has become a phenomenon without following the art market’s rules.

Former graffiti artist KAWS

Most artists work with galleries to find a niche, develop a moneyed collector base, and then wait for those buyers to donate their art to museums, where it finds a broader audience. KAWS worked backwards, developing a massive global following on social media for his toys and collectibles. Eventually, interest trickled up to some of the most powerful players in the art world.

“I had a feeling that he was going to shake up our old art-world habits,” says dealer Emmanuel Perrotin, who started showing KAWS just over a decade ago in Miami and has organized eight solo shows in Paris, New York, Seoul, and Tokyo since. Perrotin’s inaugural show with the artist in 2008—the same year KAWS designed the cover for Kanye West’s album 808s & Heartbreak—marked “the only time someone stole a work from my gallery,” he recalls.

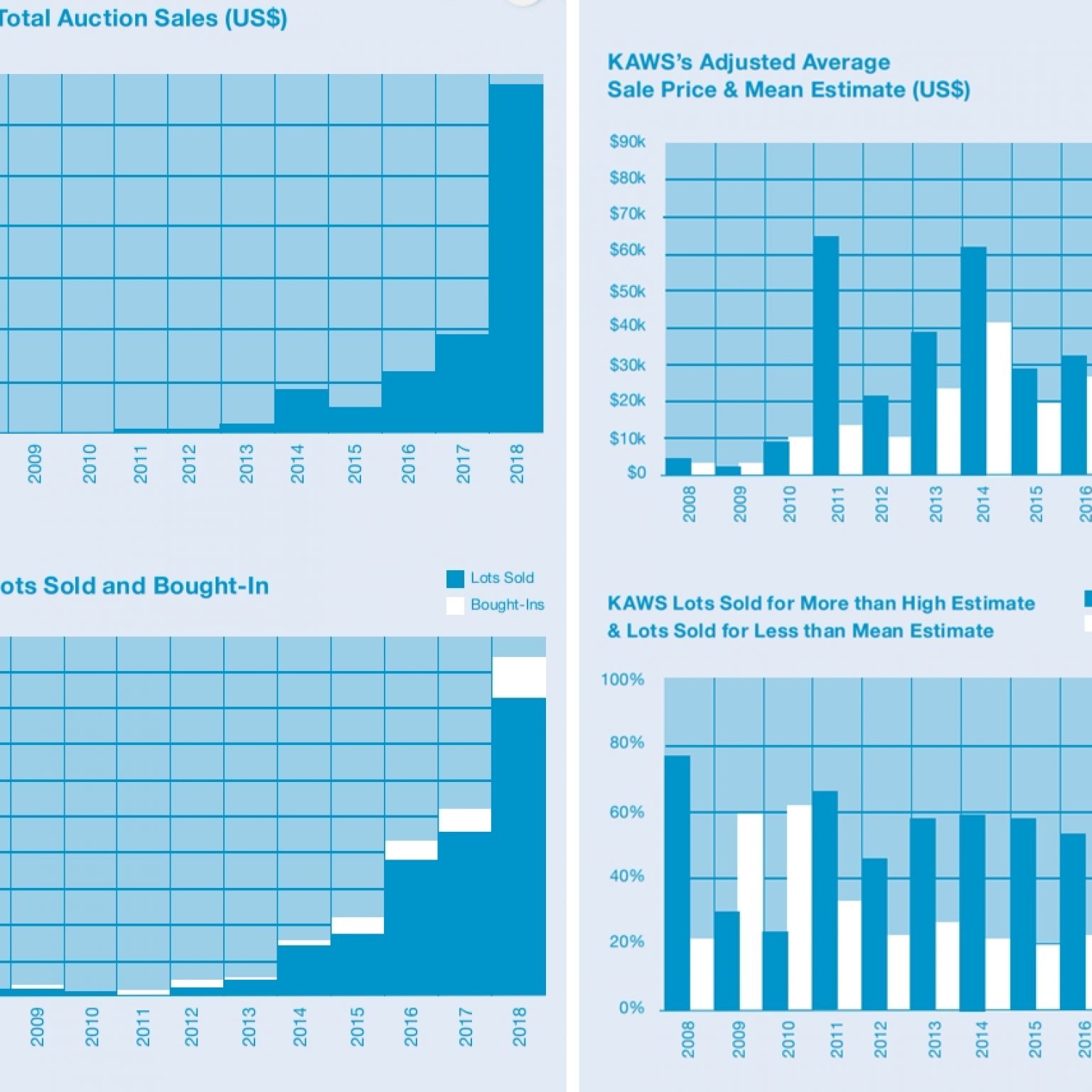

KAWS auction data. © 2019 artnet Intelligence Report.

Last year, however, a switch seemed to flip. The steady burn that had characterized KAWS’s market for the past decade transformed into a full-blown inferno. His work generated a total of $33.8 million at auction in 2018—an 113 percent increase from the previous year, according to the artnet Price Database. His average sale price also nearly doubled, from $42,272 in 2017 to $82,063 last year.

What’s more, all 20 of KAWS’s highest auction prices were set in 2018, including five works for more than $1 million apiece. On November 15, the artist’s auction record was broken three times in a single night.

KAWS, Companion (2019) floating in the Hong Kong water.

This week, his quest for global domination continues in Hong Kong, where a 121-foot-long inflatable figure by the artist has taken up residence in the city’s Victoria Harbor ahead of Art Basel Hong Kong, peacefully floating with his face to the sky. And on March 26, the Hong Kong Contemporary Art Foundation opens a survey of the artist’s work at the PMQ mall organized by none other than Italian art historian Germano Celant, the same man who coined the term Arte Povera (“poor art”).

There is nothing modest, however, about KAWS’s meteoric rise.

Graffiti Beginnings

The 44-year-old Brooklyn-based artist, whose real name is Brian Donnelly, got his start as a teenager, when, by his own account, he would shell out $1 to take the PATH train from New Jersey to New York City to leave his KAWS tag—the somewhat random letters he chose because he liked how they looked together—on downtown walls and buildings. He later began tagging street advertisements with playful, cartoon-like figures.

KAWS, New York Made. Installation view.

After graduating from New York’s School of Visual Arts with a degree in illustration and working briefly as a background painter for animated TV shows like Doug and Daria, KAWS took a life-changing trip to Japan in 1999. There, he created his first editioned toys, a series of Mickey Mouse-like “Companions” in three colors. These characters also made their way into paintings, which have become extremely sought-after.

Before long, his work was popping up all over the world. The artist’s 2016 retrospective drew record attendance to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Texas before traveling to the Yuz Museum in Shanghai. In January, KAWS erected an 11-story-tall inflatable “Companion” in Taipei, his largest work to date.

KAWS, New York Made. Installation view.

“He’s omnivorous,” says Christie’s associate specialist Noah Davis. “No cartoon is safe from being consumed and turned into KAWS.” In November, Phillips sold Untitled (Fatal Group) (2004), a painting that riffed on characters from the 1970s cartoon series “Fat Albert,” for $2.7 million, about triple its $900,000 high estimate.

But KAWS’s mass appeal has also been greeted with skepticism in many corners of the art world. “You can call me an elitist,” says art advisor and publisher Josh Baer. “I’m sure he’s a super nice guy and a great businessman. But I don’t think that the history of art will go: Matisse, Pollock, Johns, Basquiat, KAWS. If you think that Paris Hilton and the Kardashians are important cultural figures, then you’re likely to think KAWS is an important artist.”

As for the current thriving market, Baer has a prediction: “If you want to tell me that his market is great, just prepare to take one or two zeroes off in 20 years when you prepare to sell. It’s that kind of art.”

Installation view, “KAWS: WHERE THE END STARTS” at Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

Friends in High Places

Despite his detractors, KAWS has been promoted by some of the most powerful figures in the art world: namely, Alberto Mugrabi, whose family also owns the world’s largest private collection of work by Andy Warhol.

Mugrabi says he first started paying attention to KAWS around 2011, when he came across the work through Los Angeles dealer Honor Fraser. Fraser and her husband, collector Stavros Merjos, were major early champions of the artist. (Fraser was not available for comment.)

“This was like some sort of street art that I hadn’t seen before that came out of Keith Haring and all the graffiti artists,” Mugrabi recalls. “It looked familiar but completely unfamiliar. I understood that this guy had a completely different type of language.” Mugrabi and his family have been devoted buyers ever since.

Swizz Beatz, KAWS, and Alicia Keys.

KAWS’s market profile took another significant leap early last year, when high-profile dealer Per Skarstedt—who works with heavyweight artists including George Condo, Georg Baselitz, and the late Martin Kippenberger—began representing him. Mugrabi says Skarstedt was initially skeptical about the idea, but eventually agreed to take him on. It took Mugrabi about a year of lobbying and cajoling for the dealer to reconsider, the collector recalls. (“We always like to do our homework before we sign on a new artist,” Skarstedt says in response.)

The artist’s first solo show with the gallery in November, “GONE,” featured four new large-scale bronze sculptures and a series of new paintings—all of which, not surprisingly, sold out. “We monitor the primary market sales very carefully and are focusing on placing his works in serious, private collections and institutions,” Skarstedt says.

Other famous collectors have boosted KAWS’s profile outside the art-market bubble. Reality star Kylie Jenner and her boyfriend Travis Scott as well as musicians and producers Swizz Beatz and Pharrell are known buyers of his work. KAWS collector and Chinese contemporary art expert Larry Warsh says he has not seen anything like the energy of KAWS and his work since the 1980s, when he began buying work by Basquiat and Haring.

Mass Appeal

KAWS has not taken the typical path to art-market domination. “Everyone in my generation knows KAWS, and not because we saw a show at Skarstedt,” says Leon Benrimon, Heritage Auctions’ director of modern and contemporary art.

Mugrabi made a similar observation. “Collectors would come to my office to look at Warhol or Basquiat and tell me, ‘My son or daughter wants me to look at KAWS.’ That was insane—it showed me the generation to come was leading the way. An eight-year-old? A 24-year old?”

Installation view, “KAWS: WHERE THE END STARTS.”

By press time, over 900,000 photos had been posted on Instagram with the hashtag “KAWS”—more than the number for either Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Jean-Michel Basquiat, or Andy Warhol. In 2018, KAWS was the 24th most-searched artist in the artnet Price Database (one below French-Chinese market force Zao Wou-Ki, but one above Banksy).

Part of the appeal may come from the fact that, unlike the work of some artists, KAWS’s richly saturated, flat, Pop-inspired compositions reproduce faithfully online. Suzanne Gyorgy, the head of Citi Private Bank’s art advisory, says she’s “talked to people who are building a business just by selling KAWS works on paper online, via hashtags.”

“I think we’re seeing the effects of how the art market has gone global,” says Jacob Lewis, director of Pace Prints, which has now released about 10 print editions with KAWS. “Social media is telling the marketplace what is important culturally.”

Installation view, “KAWS: WHERE THE END STARTS” at Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

KAWS’s institutional projects have similar reach. Andrea Karnes, a senior curator at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, was surprised to see visitors flocking to a small show of the artist’s work at the museum in 2011.

“I didn’t have an understanding at that time of KAWS’s audience,” she says. “Every time I went over to the galleries it was a different crowd and just an entirely new demographic. It was younger people who were very engaged with what they were seeing.”

Whether this broad appeal will translate into long-term sustainability remains to be seen—though some are betting on it. “Collectors who in are in their 20s or 30s might not have the means to buy a painting right now, but when they do have more disposable income, it will the same sensation that started happening 15 years ago with Warhol,” Leon Benrimon says.

KAWS, Untitled (Kimpsons Blue #3)& Untitled (Kimpsons Blue #1) (2008). Courtesy of the Modern Art Museum Fort Worth.