In the modern day, where relevance is almost directly correlated with social media presence, we are encouraged to categorize ourselves. We are one thing and one thing only. This however does not portray the whole picture for a creative. Creativity is not one single thing, it is a lifetime of lessons learned, failures and triumphs—a complex construction of seemingly unconnected experiences.

On Wednesday, November 7th, MAEKAN and Imprint come together to bring you the Unexpected Connections Conference. Throughout the day, speakers from all sides of creative culture will explore the ways in which their everyday life intersects with their professions.

To find out more information, including who will be speaking at the conference and how to get your tickets, head over to http://ucc.archive.maekan.com

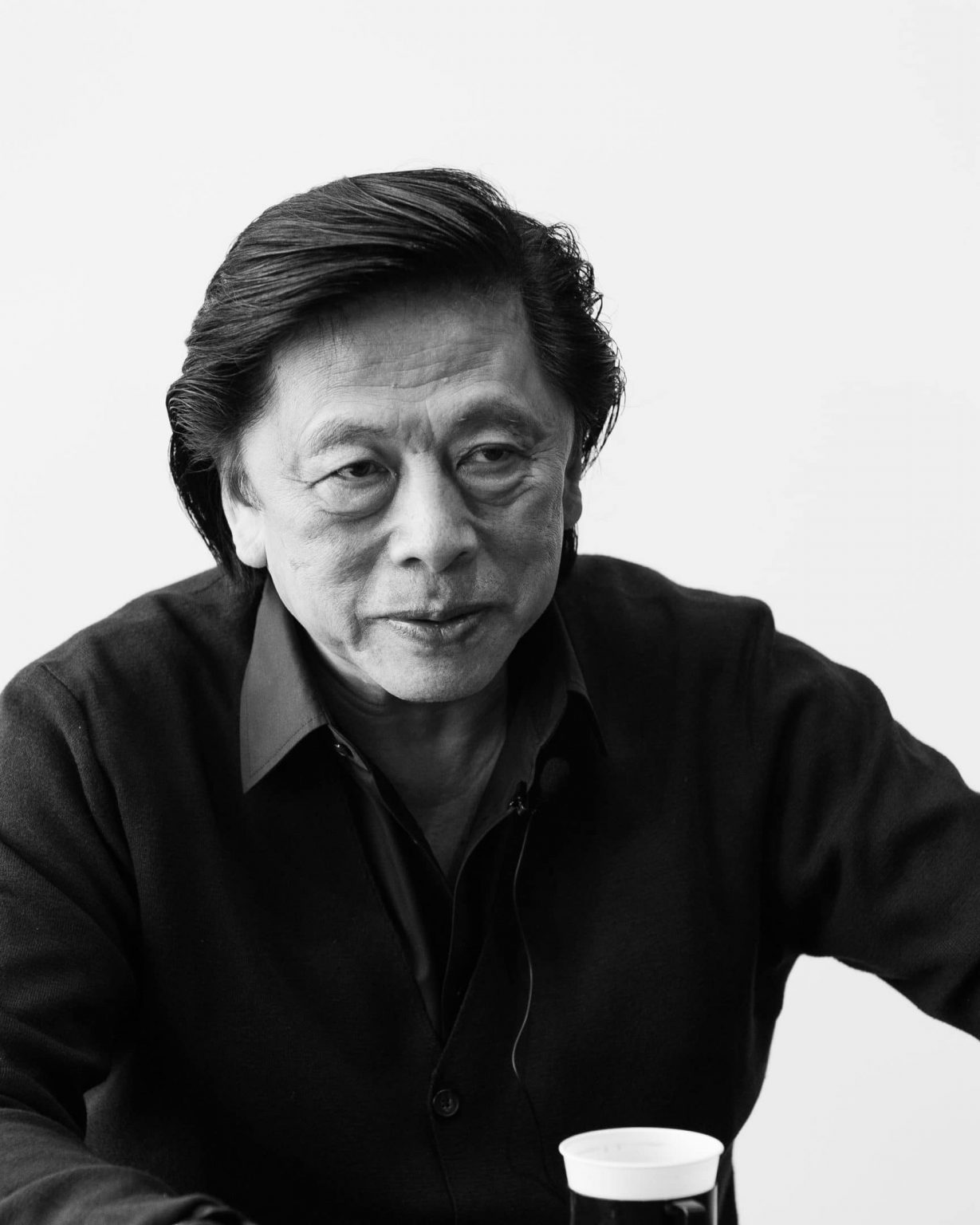

John C Jay is the President of Global Creative for Fast Retailing Inc. who own Uniqlo. Before this, John was the Global Executive Director of Wieden + Kennedy. After a lifetime of being the hardest worker, his mindset is unchanged. Now, with the opportunities and know-how, John is embarking on new projects more often than ever before. A burning desire for knowledge and experience makes John the epitome of the unexpected connection. Whether it’s street-basketball, fashion or ad agencies, John has been in the thick of it. Seemingly disparate experiences and interests are brought together in John’s ability to take what’s necessary and apply it to any professional, family, social situation. Since he can remember, John has refused to be categorized and this isn’t going to change any time soon.

“I always made it happen. I didn’t know how, but I always did. I didn’t know jack shit, but somehow I always did. So that’s what comes from my ability to work hard, really hard, because I know that if you put a penny in the bank, it’ll come back. So I work harder today than I ever have.”

At MAEKAN, the story defines the medium. Some stories function best as written text, others hope to capture the emotion through an intimate audio experience. In cases such as this audio story, the transcripts we provide are done to the best of our ability through AI transcription services and human transcribers. We try our best, but this may contain small errors or non-traditional sentence structure. The imperfection of humans is what makes us perfect.

John: Hello.

Eugene: Thanks a lot for your time. I’m going to try to make this concise and brief and I also want to give you a bit of update on the conference and sort of the seed behind the idea. We’ve been trying to distill what we wanted to achieve, and a lot of it stemmed from the idea that currently in this social media-heavy landscape, we’re inclined to put people into buckets because it allows us to understand them better. But I think in general, we as humans have a lot of complexities that might not necessarily be what we’re known for and I think those interests, those passions are just as important in developing who we are and how we operate on a professional level. More recently I’ve come to terms with the fact that the digital brand is pretty boring because it doesn’t allow us to actually talk about other things because the minute there’s some cognitive dissonance: ‘Oh I thought you were a sneaker designer, I thought you were a painter.’ And you do things outside of that realm then people kind of get confused and I think there has to be a pushback against that.

John: Well, first of all, you’re whistling my tune here because I’ve spent my entire career defying those categorizations and I’ve talked about that in the past in some interviews. That’s exactly what I try to do and even when I work at a full-time job and have a position like president of this or that or whatever, I still am doing other things and if nothing else, sometimes just to fuck with everybody.

Eugene: Yeah, I got you. I guess the first question I want to start off with is: When you were growing up did you identify an early passion? Something you really gravitated towards?

John: Not really. Part of that is the Asian syndrome of having these inklings of creativity or art or something, but you’re told by your traditional parents, ‘Well, don’t do that!’ And you know, ‘You can do that if it’s just a hobby or something, but you’re going to starve.’ And so on and so forth, so there was a lot of that in the air. You may know my story, but I didn’t live in a house until I was 15. I lived in the back of a laundry. I had no furniture and I used to tell people my biggest dream, the American dream: “One day, I’ll have a sofa.”

Eugene: How do you think that inability to express or find a passion revealed itself when you were older and you had the ability to choose what you wanted to do?

John: Well, being the first to go to college certainly was important and going and finding my way by luck into design school, into visual communications, running into European professors teaching the grid and Bauhaus and all that Swiss stuff and then looking at foreign magazines like Domus and all of that opened up a whole world for me. I grew up two miles from Ohio State University. It never entered my mind to go anywhere else but Ohio State. I had no notion of going abroad or of going to another city. My parents couldn’t afford it anyway. But that idea wasn’t even implanted in my head. Just going to college was a big deal. But certainly education, that opened the world to me. I remember as a kid, when I was 10 or something, sitting in the laundry and just trying to imagine 20 years or 10 years, where will I be? Is there another city in the world where I’d like to be? I had no idea what I was going to do at that time, but I clearly had creative interests, but that didn’t mean I had professional creative interests.

Eugene: Obviously now, over the course of your career, you’ve traveled extensively. Is there something about growing up in Ohio or growing up in a less metropolitan area that has grounded you in terms of travel and exploration? If you grew up in New York for example, you might have taken everything for granted.

John: I’ll tell you a couple of stories. One, I was walking across the campus—I can’t remember what year this was, whether I was a sophomore or junior or whatever—and I saw an envelope on the ground and ran over and picked it up, opened it up and there were two tickets to Paris on T.W.A. and they were tickets for a professor. Now, the story doesn’t end with an adventure where I go to Paris using those stolen tickets, I was still a dutiful Chinese son. But I remember taking those tickets and holding them, literally holding them at home against my chest thinking somehow through osmosis: one day I will go to some faraway place like that, like Paris. Earlier, there was a family friend who was a nurse and after graduating from nursing school she went to Paris and I remember I was living in the laundry at that time. We got a postcard and I was much younger then, I didn’t hold it against my chest, but I remember holding that postcard and looking at the postmark: Paris, France. I thought, this is like something from Mars. It might have been from another solar system it was so far beyond my reach of understanding and thinking that I could do it myself at that time. Now I travel like a flight attendant with an overdue mortgage.

Eugene: You’ve had a very extensive career. How do you look at the development of new passions? Do reach a point in time where new passions are much harder to come by?

John: No. My problem is I’ve got too many goddamn new passions, all the time. Right now I’m starting a new art building. I just bought a small warehouse, three stories with a parking lot and I’m just planning my first event, I just demoed the first floor, adding video installations and stuff like that. If I’m working 23.75 hours, that last 0.25, I’m going to put it to another personal project. I’m pushing it and no matter how old I get, I’m going to keep pushing it. In fact, I’m pushing even harder now.

Eugene: Why do you think you’re pushing it harder now than in your more youthful days?

John: Because I know more now. I know what the opportunities are and and I’m very fortunate, because of my career I have these opportunities. I can afford to buy that warehouse today. I can pick up a phone and someone will say: ‘Hey, what do you think about doing a film or something?’ ‘Okay, yeah. Let’s do it.’ I have unlimited connections now, people drop stuff on my lap.

Eugene: So do you also think you’re in a much better place to just make sure it happens versus when you’re younger you’re trying to figure things out in the process?

John: I always made it happen. I didn’t know how, but I always did. I didn’t know jack shit, but somehow I always did. So that’s what comes from my ability to work hard, really hard, because I know that if you put a penny in the bank, it’ll come back. So I work harder today than I ever have.

Eugene: Yeah, that’s really interesting to hear and I think it’s a really refreshing outlook. I think that there’s a lot of people out there that look to people who are doing things in the creative sphere and they’re like: ‘Oh man I wish I could do that.’ You meet people that struggle to define a passion or find a passion. Why do you think that is?

John: I have a lot of long conversations with my sons, my sons’ friends. A lot of it is blamed on too much information, too many choices, everyone art directing their life to make it look like they’re all glamorous. So many choices. We all know that even from a retail standpoint, this over-abundance of choices has made it very confusing, so it’s difficult for people to choose, number one. Number two, there’s a fear of failure because everyone’s life seems to be more glamorous than yours. The pressure amongst young people not to fail is immense. For me, I see so many exciting things that I haven’t done yet and so many exciting people that I haven’t met yet and I’m thinking, ‘holy shit, I wish I could meet him’ and I always make this happen.

I put a list together sometimes. a short list like: man I wish I could meet that person. For no business reason, but just the sheer joy of standing and being in a room with someone brilliant and smarter than you and more talented than you and just soak it up. Since I left Wieden, my world has exploded and and when you think about that, being at Wieden, the best agency in the world bar none, it’s still independent, it still can say ‘no’, it’s still creatively run for the most part. So to say that I’ve stepped out of Wieden and now my world has exploded. Well most people would say my life at Wieden was already an explosion. Working hard is the best investment. There are very few investments in life that will guarantee a return and I’d say working harder than anyone else is the most incredible investment that you can make.

You said that the concept of the conference and your objectives are evolving, how so? What is the main thought of the conference?

Eugene: I think it’s less about an evolution, it’s more of a distillation. It’s more about: I think that if you were to get interviewed, more often than not it’s like, ‘let’s talk to John about what he’s known for, but we want to talk about what he’s not known for. What are the things that he personally has never been given a platform to talk about?’ Because those are arguably just as important, you talking about this new art project for example. The way you talk about it, there’s a lot of passion and interest and excitement and that should be just as important as things that you’ve done in the professional realm because if you zoom out far enough you can see they’re all interconnected.

John: This is not fodder for the conference. It has to do with your categorization, your accusation of social media always putting you in a box. I’ve always fought being put in the box, starting with being Chinese and the eldest son of an immigrant family: the box was engineering, the box was medicine or law or whatever. I refused to go into that box. So even though I didn’t really understand what I was doing, clearly that’s been a big part of my life. So one of the things about not staying in the box is that it may end up – and I might say this is true with me – that you’re not that well known in any singular area because people can’t wrap their heads around that. I’ll give you a small example: I sent a link to Bobbito’s new film to some executives at Uniqlo and I said, “I want to send this to you because this is a part of me that you don’t understand. You think of Wieden. Okay, maybe my Nike connection and all that kind of stuff, but I’m in this film and I was on the ground floor of streetwear and sneakers and all of that way before all of the stuff that you see today.” I was with the Bobbito in his apartment, I introduced him in 1993 to Nike and in 1997/98 I introduced Hiroshi to Mark Parker.

So I’m in there on the ground floor of two major plateaus of this whole thing. The reason I’m thinking of this is because I’m being asked to talk about this in Italy in the future. So, the Japanese executives have no idea that I have a street name, that I know basketball heads: Pee Wee Kirkland and all these street basketball stars. This has happened in the past when my book came out and the opening event was at the photography museum on Fifth Avenue. A lot of fashion Bloomingdale’s people came and a lot of street people came and the fashion people go: ‘Dude, how do you know those those minorities? How do you know those African-American kids? How do you know all those hip hop guys?’ And the hip hop guys all go to me: ‘Woah, what are those fancy white people over there? How do you know them? Those are like fashion people, how do you know them?’ So I walk in these very different circles of life. So again to your point about categorization, I’ve been able to purposely live simultaneously in many of these silos.

Eugene: That’s a good consideration. There’s not really a right or wrong answer. You’re 100 percent valid that building a brand requires you to do something really well that you’re known for but then it’s almost all the things behind the scenes that are constantly pushing you to evolve and to improve.

John: On the other hand, my advice to young people who think they can do everything when they come to me: ‘Well, I read about you, John, and I want to do what you do. You seem to travel everywhere and you get to do all these creative things and you meet all these fancy people. I just want to do what you do.’ And I say: ‘First of all, you have to be good at something. I was an art director. I am an art director. I started in magazines, I love the combination of words and pictures to create emotions through stories. That’s what made me different in advertising. I came through that channel of communications. So I was good at designing, paginating, telling stories from the cover to the upfront pages, to the middle of the editorial well, to the finishing of the book, so I could pattern a book, the journey through an issue of a magazine. So it wasn’t just like a smart, cool, cynical headline on top of a cool picture. My bosses were editors, not creative directors. So I think that helped me immensely, but I did start as an editorial art director. I can art direct. I can and still do graphic design, no matter what my title is. That’s my big fight of course, to try to keep one of my fingers on the drawing board or the computer. So you do have to be good at something. There’s no V.P. of everything and I get these young people: ‘Well I’m good at connecting people.’ Well dude, get in line. I think there’s about 700 million people in front of you, it’s called the Internet. There’s no V.P. of connecting people. You earn the money by doing something well that solves a problem, except for fine art, I’m not talking about fine arts. So for me to pay you, you have to help me solve a problem. What do you bring to the table that helps solve the problem that other people at the table can’t do? How will you help me solve the problem? What is your skill? Your skill can’t be ‘everything’ or ‘connector’. We’re all connectors. That’s just part of the game today. So what do you do?

Eugene: That’s definitely been a point of contention especially for us on the ‘business development’ side. Trying to sell what you offer and distilling what you have as a value proposition in the unsexy business terms like: What are ways I can help you? And then what does that look like?

John: The question is, to you or to anyone else, and how I started every assignment at Wieden to the client: Why do you exist? Let’s be honest about that, and then why should I care? You have to express why in the world you should exist and why should anyone pay for your service or your product. Why should anyone care about you? Why? What’s your point of difference? So just two questions: Why do you exist and why should anyone care? If you can’t answer that, go back to sleep.

Eugene: Yeah that’s it, and would you say that this question still plays a part in your mindset?

John: I just spoke in Hawaii last week and although it was twelve hundred businesspeople, The Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu and Mr. and Mrs. Yanai were there. I opened it with the question: What is the most important word in our vocabulary? And my answer was ‘why’, and I showed the cover of the book Why? and the concept of ‘The Golden Circle’ which asks: why do you exist? So people buy why you make something, not necessarily what you make or how you make it. I started with that and the whole concept of ‘why’ and I used ‘why’ as the ongoing theme through the talk.

Eugene: Why do you think people are so caught up in the ‘what’ though?

John: Because it’s easier to understand. It’s easier to answer. I make a thing with 103 stitches and with the hand-eye da da da…But why? Why do you make it? It’s very tiring to use Apple examples because they’re so good and overused, but in the book he talks about Apple of course and that Apple—and I would say Nike at its best—always talked about why they made something, why it would make a difference to you. It’s a shorthand version of ‘why do you exist?’ This world doesn’t need another apparel company, it doesn’t need another sneaker company and doesn’t need a magazine. Why, why, why? Why should you exist? Why? Sometimes the answer is not sexy: my name is Skechers and the reason I exist is to copy everyone else’s shoe or whatever. Okay. If that’s the honest truth then okay. How are you going to make me care about that? By the way, is there a title for the conference?

Eugene: Yeah. So we’re going with Unexpected Connections. The reason being for example, you at the event connecting people who had no idea that you were walking in all these different spheres. I think you’re in many ways the epitome of the unexpected connection. Who you know, why you know them and how it all forms part of the bigger picture.

John: So, when you think about the ad agency world, and I know you’re from Hong Kong, you may not know the U.S. ad agency world as well, but only recently has any ad agency person been mentioned in the world of street culture, probably because of how commodified the whole thing is. But in in my life at Wieden, I brought many people to the agency and to the client: I start with Hiroshi as one and Bobbito as another: two different eras, two different cultural advancements. That’s pretty rare in an ad agency. Although I did not agree with his position, when Jeff Staple put me as 14 or 19—I can’t remember—in his “important people of sneakers.” Jeff, you’re confusing me with all the collective work with Wieden & Kennedy and Nike. But clearly there’s no one else in the ad agency world that would appear on that list and I take great pride in that, because then on the flip side, if you go to the street world, you don’t have a president of a major apparel company or a partner of an ad agency either. So being able to appear on these different lists was kind of like a funny game for me.

Eugene: Yeah. I think that it’s interesting to see it all play out. This is continual discussion: in many ways, 10 years ago or 15 years ago, even before that, authenticity seemed to be very easy to find. It was rooted in the act of doing something and the easiest way to see if someone was inauthentic was if they were commercializing it or selling out. Now, it feels like authenticity has either changed or the level of authenticity that is expected has changed. So, us being sold something all the time or the next generation that’s being sold something all the time, they won’t know what authenticity was defined as a generation or two ago. So that’s something that’s interesting to me because it’s like, does authenticity in the sense that we knew it even matter anymore or do I need to relax my standards to maintain a level of relevance because if not I’ll be out-competed for example?

John: Yeah. Yeah well there’s a little bit of truth in all of that. The other side is the Bloomingdale’s side. I said to a visiting president of F.I.T. who came to Japan: ‘If I did a half-hour or one-hour story on my more than a decade at Bloomingdale’s, the stuff I would show you, the work that we did would be so far beyond what the students could even imagine. They couldn’t even grasp what we were doing because it is so many lightyears away from what they’re able to do today.’ So when I stepped into Wieden, I had already worked with Steven Meisel and Herb Ritts and Lord Snowdon and all the best. I had already traveled the entire world, I was shooting every month somewhere else in the world. So even though it was my first agency job, I came in with a lot more experience than anyone else had in terms of cultural connections. I have all these different periods of my life and certainly I’m going through one the most interesting and energetic ones now. So what do you think I can do at this conference?

Eugene: I think first and foremost your presence is obviously critical in terms of bringing a sense of credibility and thoughtfulness because one thing that I’ve really looked at is: how do you create this valuable experience for people? I think the experience is the most critical thing because while we might not have the scale and size of traditional conferences, how are we able to create a more humanistic touch point with people? And allow people to know that the goal here is to bring together people that are leading the way or providing interesting provocative points of view and how we find a way to help each other, whether it’s in a professional or cultural context?

John: I wonder, going back to why do you exist. Let’s ask a question about the conference, why would someone pay to come? Well, in the old days they’d pay to see Hiroshi or or even Jeff or someone like that. Ten years later, why would someone come to this conference?

Eugene: Yeah, I would say that in general the way that I’ve looked at it is that a lot of the things that we’ve deemed to be good enough—like everything on the internet is ‘good enough’—don’t necessarily replace the face-to-face interaction that we can achieve. But also I think there’s something to be said about having the opportunity to be in the same room as someone, to have the access to these great minds. Being in the same room with somebody is a very different experience to listening to them in an interview that’s edited. I think that live format is what’s critical to this. Seeing people make mistakes, seeing people change their cadence if they’re trying to figure something out. I think that those are the subtle nuances that represent why live things are so big and important.

John: Yeah. Well it is true and if you just think as a consumer, maybe the experience is enough. I mean, why do you go to Burning Man and shit? Maybe the experience is enough. But this costs money, right? Young people’s hard earned money, so other than just the experience, is there something that they want to fulfill? Is there an answer? Many times they’re looking for some answer or some way you know to help them. I just sense from my son’s friends there’s so much confusion out there right now, just so much confusion and the confusion is because they’ve lost sight of the fundamentals and when I say fundamentals that means hard work. I know that doesn’t always play into your balanced life theory.

Eugene: I guess to that point, a lot of the people that we’ve chosen to speak are people that are doing it or have done it, and I think that to the audience, hearing those stories and the reality of how you accomplished it is probably something we should hang our hat on more because I think that is the ‘why should I come?’ Do you want to know how successful people have done it?

John: Right. It’s like when I tell people, take almost any job interview that is offered to you, unless it’s just a horrible place because when you get into that room, you can ask questions across the table to an executive that they would never answer on the internet or if you saw them out on the street. You literally get to ask them about marketing plans and the future and all this stuff. Having that one-on-one dialogue and to be able to ask things that you could learn from is a huge experience. Like you said, it’s not the same as reading it online. Am I going to be a speaker at the conference? What do you think I’m going to do?

Eugene: Yeah I think you’ve been a very thought-provoking mentor to a lot of people, maybe not in a direct one-to-one sense, but I think a lot of people look at you for mentorship and to just see your perspective on the world, and it’d be great to see how you approach that and ushering in the next generation. I think that’s something I always find really fascinating is like when the O.G. recognizes that their role in the culture changes. Like your role when you were in your mid-20s/30s was about dictating what was cool, not to say that still can’t happen but there’s also a point in time where this switch flips and your goal is almost to help the new generation execute on their ideas or to bring something into the world.

John: Right. I can’t remember, I think the first year I sat for an interview with Jeff. I think in the second year I moderated Hiroshi and maybe Jeff or something like that. Again I’m not going to overdo this but because the subject came up the other day, you don’t find any ad agency people doing that.