The Master P way

of building a music empire is no longer relevant

Post Feature

Reading Time:

Minutes

“Today’s artists want what Master P achieved, but they need to understand why his record label’s strategy would be less effective today.”

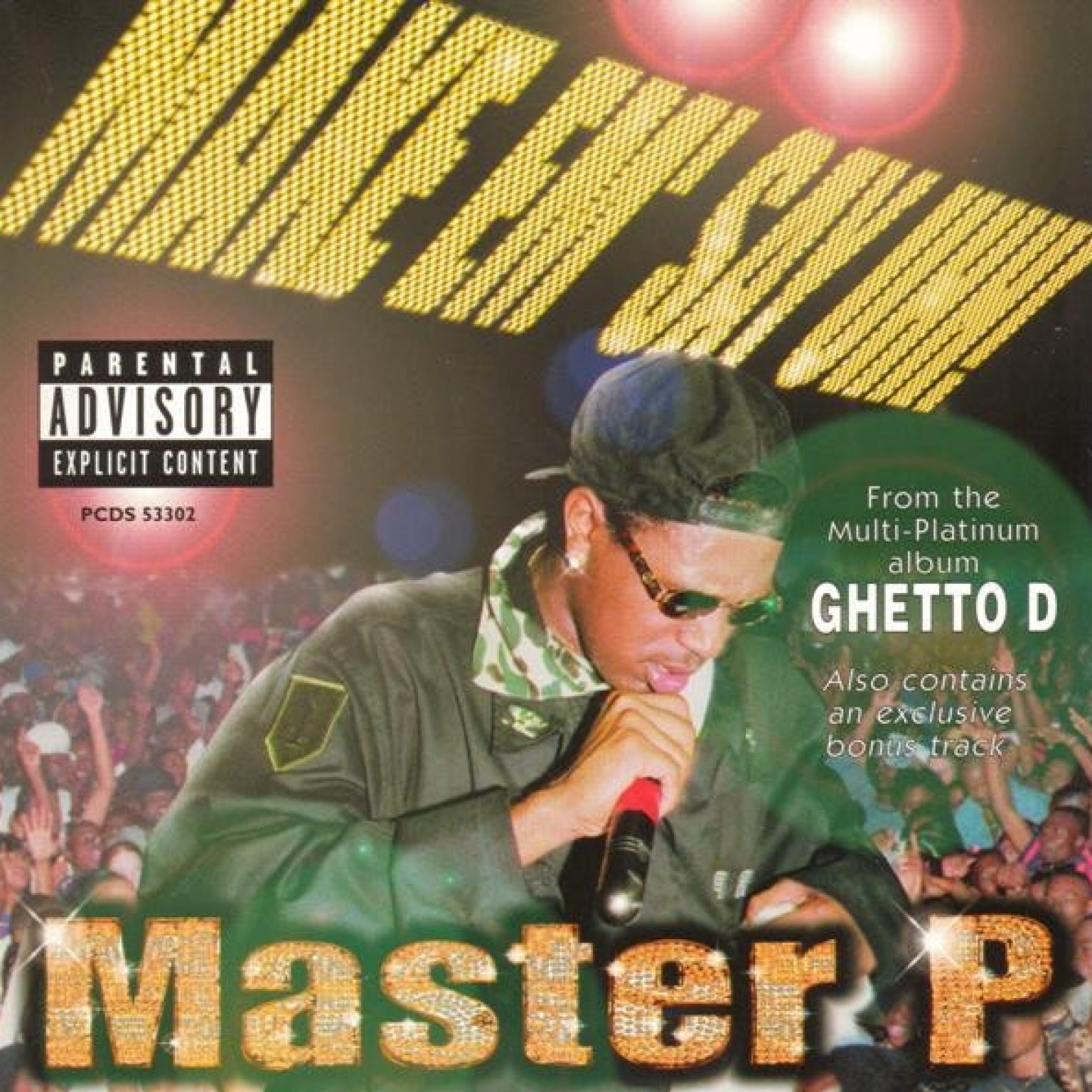

Master P’s legacy has had quite the resurgence. Last year, Nipsey Hussle rapped “We the No Limit of the West” and told Billboard that the 48-year-old businessman doesn’t get the same credit that other moguls do. Quality Control Music founders Coach K and Pee came together on a shared dream of emulating their record label after No Limit. And in last week’s Def Jam article, I mentioned that the label’s leadership wants to replicate No Limit’s sonic identity with its Rap Camp. The “Make ‘Em Say Uhh” rapper merits praise, but his strategy deserves critique as well.

No Limit’s 1998 run has its own chapter in rap’s history books. That year, the New Orleans record label released 23 albums, sold 15 million copies, and earned over $160 million. His artists were tremendously successful despite their lack of talent. One of P’s biggest feats is that his brother Silkk the Shocker—who is considered one of the worst rappers ever—went double platinum. Master P was a marketing guru who got a lot out of his company’s product. No Limit was a living testament of the Peter Principle: its talent rose to its “level of incompetence.”

But in a few short years, the label’s run ended. Cash Money Records came through with better music and put Louisiana on its back. No Limit’s releases could no longer ride the wave. The label also dealt with internal conflict, a compounding challenge for family-run businesses. In 2003, No Limit filed for bankruptcy. By then, Master P was deep in his other business interests.

Looking back, No Limit’s run went exactly as designed. The same strategies that drove No Limit’s dominance led to its demise. Those who want what No Limit achieved need to accept its drawbacks or adapt the strategy. Some of those tactics won’t work in the digital era. Others might work temporarily but will lead to the same traps. Those who idolize Master P—and not necessarily No Limit itself—need to distinguish the two.

Great marketing can only get you so far today

Music was never the end goal for Master P. Here’s what he told Fortune in 1999:

“Once you develop an audience, you take everything you’ve got and milk it. So if I’m successful on the music side, I’m going to take that success into the film business and rap to that same audience. That’s my key to success. I have a record that’s big, and I’ll put the music in the movie. If I have a movie that’s hot, I’ll put new music from it on my next record track. It keeps my overheads down.”

Branding was key. Fans identified No Limit’s popular Pen & Pixel style album covers. The brand was larger than the individual artist. This made it easy for Master P to extend into his various business interests.

Today’s artists who follow that playbook without adapting will struggle for several reasons. First, No Limit’s content marketing strategy was designed for the pre-streaming era. Fans had to hit up record stores and drop $15 to buy an album before they could listen to it. Even if fans barely listened to the album after the first listen, it didn’t matter. A sale was a sale.

But the streaming era has inverted this concept. Today, artists earn a mere 14 cents when a 20-track album is played on Spotify. Artists can’t rely on single plays. They need repeat listens, which comes with higher quality music. They also need to go on tour to make their money, which Master P never had to do during the label’s run.

Second, today’s artists are expected to build individual brands. This is difficult when the label or group’s brand takes precedence. The Migos have struggled with this in their solo careers. Here’s what I wrote in November:

The Quality Control record label, home to the Migos, Lil’ Yachty, Lil’ Baby and others, is pumping out new music like Netflix releases new original series. Many of their projects have long track listings to perform well on streaming platforms and playlists. The approach has given QC an unofficial residency on RapCaviar and The A-List: Hip Hop playlists, but that exposure is attained at the expense of the artist. The Migos would get more long-term benefit from a proper promotion cycle that builds momentum and uniquely positions each rapper.

QC and the Migos should learn what they can from No Limit, but not follow the label’s moves precisely. A lot has changed in the music industry since 1998.

I went to Walmart in ‘98 and bought this as a single! Had to get the edited version though cause, you know, Walmart.

Family business challenges

No Limit was a true family business. Sonya C, Master P’s ex-wife, was its first signed artist. Silkk the Shocker and C-Murder were Percy’s brothers. Beats By The Pound, No Limit’s in-house production team, was led by one of Master P’s cousins. And P’s son Romeo released his first album on the label when he was 11 years old. This kept talent acquisition costs down, but it also heightened challenges when conflicts occurred.

In 1999, Beats By The Pound and Master P got into a disagreement over a potential business opportunity for the label. The producers were hesitant to move forward, which frustrated Master P. His cousin overheard P tell their business partners “they don’t want to sign the contract, fuck ‘em.” The fabric unraveled after that.

The producers parted ways with No Limit, which upset the label’s artists. They didn’t want to work with other producers and were mad at P for ruining the family dynamic. And since Beats By The Pound produced almost all of No Limit’s music, it was quite a disruptive change.

Internal conflict can happen in any business, but family businesses are more susceptible to long-term damage. According to McKinsey & Co, “family businesses can go under for many reasons, including family conflicts over money, nepotism leading to poor management, and infighting over the succession of power from one generation to the next.” Many of these challenges applied to No Limit. “Regulating the family’s roles as shareholders, board members, and managers is essential because it can help avoid these pitfalls.”

Most of today’s labels hedge their bets by working with both in-house and external producers. Drake still works closely with Noah “40” Shebib but has close ties with others. The production catalog might not capture the iconic sound that a single producer brings to a label, but the business is better prepared for future changes.

Negotiation and brand extension

Percy Miller’s most transferable skills were his ownership principles. He negotiated very well. In 1996, he agreed to an 80-20 distribution deal with Priority Records where No Limit kept ownership of all its masters. That made Master P’s nonstop album release strategy that much more lucrative. Birdman signed a similarly favorable distribution deal for Cash Money Records with Universal in 1998. New Orleans hip-hop wasn’t here for the bullshit back then.

These stories are more relevant than ever today. There’s no reason for an artist like Kanye West to have signed a deal that wouldn’t have worked in his long-term favor—especially with past examples to learn from.

Master P’s overall strategy had its holes, but there’s still a lot to learn from it. Unfortunately, revisionists have clouded the reality. They reminisce like No Limit was hip-hop’s Marvel Cinematic Universe. The comparison is understandable, but it’s overly generous.

Like No Limit, the superhero franchise built a strong brand that can monetize characters who weren’t household names. Most of you never heard of Ant-Man until the movie trailer came out. Marvel knew that, and it still made over $1 billion combined from the Paul Rudd superhero movie and its sequel. The film studio’s brand thrived on the quality behind it. That’s why Marvel surpassed DC Comics—a studio with arguably more famous superheroes but less consistent quality.

No Limit also had a strong brand engine, but could only go so far with the product it pushed. If today’s record labels can replicate No Limit’s branding but bring consistent quality, they can last much longer.

If I ever start a hip-hop museum, I gotta find this tank from the Make ‘Em Say Uhh music video.

Master P’s self-reflection is on point. Here’s what he said in a 2014 interview with Vibe:

“The thing about it is, people don’t realize, I consider myself—I ain’t tryin’ to be the best lyricist—I just make music that people could feel. But I am the best businessman, I feel I’m the best hustler in the game. So, I’m always about my business, I think that people didn’t think you could do that, but when you put your own marketing and promotion money up you can control your rights.

His approach has striking similarities with the “The Pump Plan.” Today’s clout-chasing rappers leverage their limited talent to become influencers and make money in other areas. Lil’ Pump and his peers figured it out.

It’s the rest of hip-hop that needs to catch up. Just because an artist or label is not trying to win a Pulitzer like Kendrick Lamar (or get in the Library of Congress like Jay Z) does not mean he or she can get by on marketing alone, especially today.

A little hip-hop nostalgia is fine. Everyone loves to remember the iconic force that took 1998 by storm. But blind reverence won’t help anyone. Even Master P would admit that.