While working on a separate project, the MAEKAN team visited Yamayo Textile, a fabric mill in Kamitonda, a sleepy manufacturing town in western Japan. After visiting the mill and having spoken with the company’s president, we were inspired in discovering how soft spoken old-school manufacturing can still survive and even thrive in a seemingly digital-centric world.

Yamayo Textile Mill in Kamitonda, Japan.

Inside, the air is stuffy, and conversation is all but impossible amid the high-speed whir emanating from rows upon rows of knitting machines. Outside the factory, however, the surrounding town is dead quiet, save for the intermittent rain pelting the lush greenery nestled between traditional tile-roofed houses.

To your typical traveler, it’s the kind of place you would not go if your experiences of Japan are defined by the big city bustle of Tokyo — and if you prefer a slightly more laidback vibe, even Osaka. Kamitonda is a town in the textile production-heavy Wakayama prefecture. With a population just shy of 15,000, which hasn’t grown much in the past 50 years, it’s the kind of place most kids might want to leave for greener pastures once they finish school.

You’d never expect that there was, in this sleepy manufacturing town, a local textile mill that’s influencing the world of apparel through its fabrics.

We sure didn’t.

Views overlooking the small town of Kamitonda where Yamayo Textile Mill is based.

Traditional Japanese houses surround the majority of the town around Yamayo.

Engetsu Island – Located in nearby Shirahama. Known for its signature arch.

The story goes like this: The MAEKAN team was commissioned to oversee an editorial project including interviews and a ‘zine that coincided with the launch of the adidas Originals XBYO collection. There were to be some photo shoots and some interviews, straight-forward enough. The location was to be in Japan, which is always a bonus.

Now, part of the production involved covering the factory where the fabrics of this collection, as well as many best-selling adidas items, are made. So of course, when we first heard the name of the town, we were taken aback.

For most of the team, some had never been to Japan, and even the ones that did had never been to the Japanese countryside. By visiting the mill, we had unwittingly stumbled upon a story that was much deeper than we had first thought. It gave us a vastly different perspective in how ideas are actualized.

The mill was founded in 1934 producing French Terry knit inner wear. A few years later, Yamayo like many factories of the period would lend its manufacturing capacities to war efforts before returning to its original production focus afterward. It would continue to manufacture circular knit fabrics until adidas made its formal entry into Japan in 1965.

President Yamashita

In our interview with Mr. Ikuo Yamashita, a man with over 50 years in the textile industry and Yamayo’s president of 25 of those, he recounted the arrival of adidas’ in Japan and the German sportswear giant’s influence on the sportswear industry.

“Before that, Japan’s sportswear consisted of plain white shirts and pants,” he explains. “Japan’s uniforms at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics were this way. It was when adidas came that the market for color sportswear in Japan began.”

It certainly seemed to be more than just about putting in the time and keeping things simple. It was just as much about playing your cards right and making friends with the right people, as Yamayo certainly did at the time.

From there, the relationship between the two would only deepen. As adidas grew, so did Yamayo. Each round of orders from adidas allowed for the purchase of new machinery and the expansion of the mill’s innovation and development. And crucially, one of the items made for adidas wasn’t just a bestseller.

It was life-saver.

“In two years, that 2.4 million dollar deficit disappeared. There’s history like that at this company. So, whatever Yamayo and adidas do, that’s where we started from.”

Yamayo is also known for its handling of many different fiber types beyond the cotton that the region is known for. These include synthetic fibers like polyester, which are derived from oil.

In the early ’70s, the Oil Shock skyrocketed the price of oil. Furthermore, these astronomical prices were compounded by the effects of the 1973 stock market crash. A large purchase of yarn at the inflated price followed by a sudden sharp drop resulted in a huge deficit that sent Yamayo into the red.

But by chance, adidas released a track top in honor of German football star Franz Beckenbauer soon after.

“In 1975, adidas’ Franz Beckenbauer model track top became a hit when it exploded in popularity,” Yamashita remembers. The result? ” In two years, that 2.4 million dollar deficit disappeared. There’s history like that at this company. So, whatever Yamayo and adidas do, that’s where we started from.”

That item certainly saved the mill. Regular orders that adidas make to Yamayo keep the mill humming along year-round. But trust is a two-way street, and Yamayo has kept up their end over the years.

First, they’ve made sure that adidas were among the first to know about its newly-developed fabrics. Secondly, Yamayo’s other mill in Wakayama City is huddled close to competing mills, which makes secrecy a key issue. Yamayo’s Kamitonda mill, on the other hand, is comparatively secluded, meaning that the process behind fabrics made for adidas remains a secret.

And these aren’t your run-of-the-mill fabrics. Given its long history and competition with other big sportswear brands, adidas is constantly pushing the technical demands of its fabrics, many of which you could argue only a factory like Yamayo can produce.

Nowadays, when we imagine a fabric mill, we picture a large dingy factory crowded with workers in a developing country. Sure, that might be true. But, as the quality of living in neighboring China has risen, so too have the demands of its factory workers. This phenomenon has lead to a pronounced shift away from the world’s traditional manufacturing hub to emerging economies such as Vietnam or Myanmar. But with the lower wages also comes a pool of experience and talent that is although establishing itself, still catching up to decade-old outfits like a Yamayo.

So what makes Yamayo so special that adidas would call on it for its latest collection? It’s important to mention that it predominantly knits fabrics using circular knitting, which typically produces lighter, thinner fabrics in a tube shape. Think the fabric in a t-shirt and naturally, the type that goes into athletic wear. Flat knitting, on the other hand, produces flat sheets of heavier fabric — like in a sweatshirt, for instance.

While circular knitting isn’t as fast or efficient as flat knitting, what sets Yamayo apart is that its workers regularly tinker and tweak their machines with custom-made parts to produce different knits. This ability to specialize so heavily in mastering one style of production is essential when your client keeps cooking up all kinds of technically-demanding recipes off in little Herzogenaurach, the small German town where adidas itself is based.

So where are we going with this? What does it matter that a meticulous German sportswear giant based in a small town and a meticulous Japanese fabric mill also based in a small town are partnered and are both succeeding?

The answer becomes clear when you take a look at one key variable, presence and especially Yamayo’s position. Its success serves as an example of how a comparatively smaller, quieter creative enterprise can — through the sheer quality of its product — make an impact that’s much larger than its physical or even its digital footprint.

“If you spend enough time in Japan and other parts of the “old world,” sights like these don’t seem that far off.”

adidas is adidas. Its ubiquity comes thanks to a driven promotional strategy that extends across all platforms. Its social media-integrated push allowed adidas Originals to firmly embed and keep itself relevant in the culture while managing to retain its sporting heritage.

Yamayo, on the other hand, is just the factory that makes fabric for them. It has no need for Facebook or Instagram.

When walking through their office, it’s complete with wooden walls and desks cluttered with documents. Their factory is filled with rows of yarn racks, knitting machines and technicians hard at work.

But suddenly it makes sense.

What we were looking at was just more proof that “this way” of doing things — the old-school “do it right even if you don’t do it fast” — was still very much alive and still very relevant.

And it isn’t simply because the past decade has seen the explosion of a demand for all things hand-made, artisanal or vintage. True, some brands have leveraged this value placed on “heritage” to market as traditional or of unbeatable quality. But once you look past the Instagram filters and retro logos painstakingly made in Illustrator, the result remains inauthentic. It’s not about these labels “steeped in history” that were founded in the 2010s. It’s about the ones that let their work do all the talking and leave the social media to the kids.

The fact that Yamayo exists and is still doing things comparatively old-fashioned is both surprising and not at the same time. For North Americans, the surprise recalls Christopher Payne’s urgent attempt to document the last surviving fabric mills in America, which largely disappeared as the country’s manufacturing moved overseas. These kinds of factories are just not what we expect when we think about how stuff gets made. Yet, if you spend enough time in Japan and other parts of the “old world,” sights like these don’t seem that far off.

Photographer Miko Lim works with his tech team to prep the lookbook shoot for the XBYO collection in Tokyo.

Japan retains a lot of its craftsmanship heritage and people the world over have noticed it. People still covet their kitchen knives, their lacquerware and of course, food. Over time, there’s a common thread between them and many traditional craftspeople: many choose one craft and stick with mastering it for eternity, maybe even with a Sushi Master Jiro-level of fanaticism. The kind of masters we’re talking about here are the ones that haven’t “caught up with the times” and maybe don’t need or want to.

By focusing on doing one thing well — such that the end work becomes someone’s go-to when they think of a knife, a food, a piece of fabric — it seems that quality and the popularity it generates are all that’s needed to create tangible success.

Crucially, this attention to quality first applies regardless of the size of the operation, whether it’s a single artisan making small batches out of an atelier or a factory producing tons of high-quality materials like Yamayo does. In their case, the metrics it prizes aren’t likes, shares or engagement, but perhaps more simply, sales.

Mr. Yamashita counts one of his life’s greatest achievements as having worked at a factory that produced four separate one million-item best-sellers. The first was the Franz Beckenbauer jersey, the second was a crewneck sweatshirt, and the third and fourth were kits for the Japanese national soccer team.

He is optimistic this latest collection is the fifth.

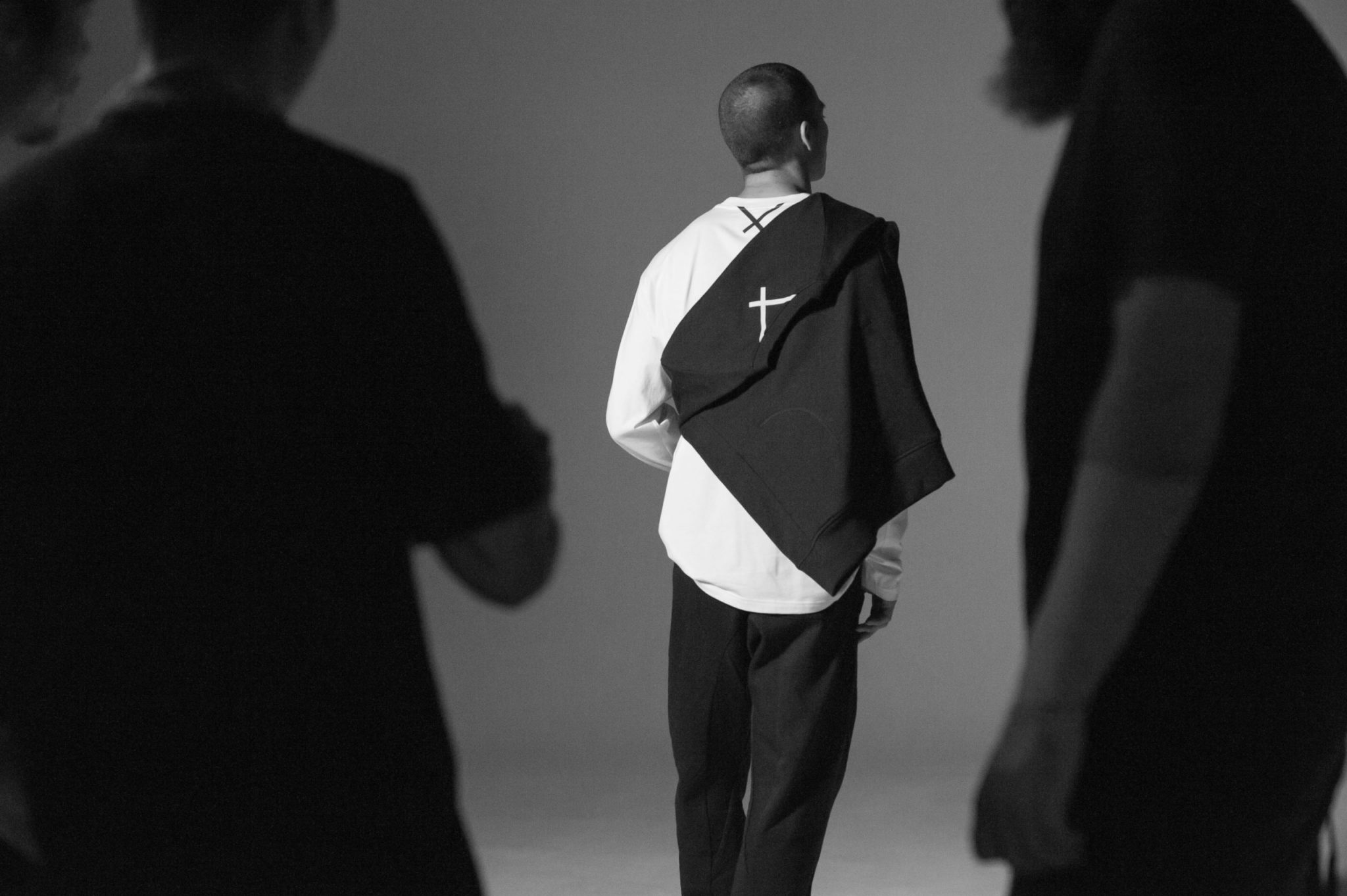

A behind-the-scenes glimpse of the XBYO lookbook shoot.

The tethered iPad monitor that allowed us to review photos in real time.

One of the final shots from the XBYO lookbook shoot.

The Faces of Yamayo

Yamayo Textile owes its success to the many skilled workers that help to produce and inspect the fabric as well as maintain the mill’s machines and operations. Many of them were gracious enough to pose for pictures, a small sample of which are included here.