Virtual pets are nothing new, and over the course of several decades, we’ve seen their most popular forms fluctuate in portability, accessibility and how we interact with them. Their latest digital incarnation in the form of mobile apps sees them back in our hands and with us 24/7 as they were with the first virtual pets over 20 years ago. But while they could easily be written off as novel trinkets or low-difficulty games, it’s impossible to ignore why they’ve stuck around for so long and why they’re still relevant to our lives today.

How It All Began

You could say it was the Game Boy of 1989 that entered the scene as the first ever portable distraction, a distant ancestor of the modern smartphone. A few years later in 1996, Japanese toy maker Bandai released the Tamagotchi, quickly making it one of the most sought-after toys of the time. Periodically reminding the owner to feed it, play with it and clean up its waste, it was considered the first-ever virtual or “digital” pet.

As addicting as those handheld gaming devices were, their experiences, except for the pre-Candy Crush e-crack known as Tetris, were largely finite: You could sink dozens of hours into a game only to reach the final level or boss and consider yourself ‘accomplished.’

But what made virtual pets different?

For starters, Tamagotchis were always on, demanding your attention in real-time. Assuming you were a diligent caregiver, they stayed happy and healthy for the remainder of their programmed lifespan. And if you found yourself grieving after they inevitably reached it, you could simply reset them and start again.

They were as the iconic virtual pet’s inventor Aki Maita had envisioned: a fulfillment of the Japanese people’s love for handheld gadgets and pets, especially given many apartments there forbid dogs and cats. To this end, they were as portable as they were clean and economically feasible.

They also “depended” on you.

Through a series of beeps, they could cry out with enough urgency to convince you to stop what you were doing and frantically rifle through your pockets, or leave the classroom to check your locker on a “bathroom break.” Sounding familiar?

Tamagotchis were banned in many North American and Japanese schools for being distracting.

Security Animals for Grownups

This is where the comparison ends as the iPhone is a highly evolved beast compared to that old jagged jumble of black pixels on a monochrome LCD. Because it’s not just the graphics or the size of the device that’s changed significantly: the relationship between you and your device has both deepened and inverted.

In short, you now depend on it.

A Tamagotchi would ‘notify’ you of its needs only every few hours or so and even those needs were numbered: it only needed to be fed, loved or cleaned. Once you’d done one of those three things, you could go back to your life for a few hours.

Regular events add variety to the experience and chances to collect unique items

As the modern security animal that accompanies us into adulthood, smartphones are not only remarkably similar to the Tamagotchis we once obsessively doted on, they’re much worse.

Each app we install has the potential be a demanding “pet” of its own, constantly begging for and splintering our attention with notifications every few minutes. Once you factor in social media, it’s no longer just a few app processes calling out to us for a tap or swipe, but potentially our entire network of living breathing colleagues, friends and family and the happenings in their lives demanding a reaction.

With this in mind, it might not seem so far-fetched to suggest that now is a great time for virtual pets to make a comeback.

Each pet type has its own personality and is based off a real breed such as the Turkish Angora pictured

The Next Generation of Virtual Pets

Based in Seoul, Hogyeong Kang is the CEO of Applepie Studio and the creator of virtual pet app Hellopet. Speaking with him through an interpreter, we found the needs filled by virtual pets have changed very little in two decades:

“Because people and users have their phones with them 24/7 and they’re able to have their phone on their person when they’re going to work, they have this opportunity to bring this pet with them.When you have a dog or cat, it just stays at home, and you can’t take it to your office. So the main focus became that it was a healing experience for many people. A lot of people are obviously very stressed with work and the like. But the benefit of having your phone with you is that you can have this interaction and conversation with the animal on your screen.”

Hogeyoeng at Applepie Studio in Seoul.

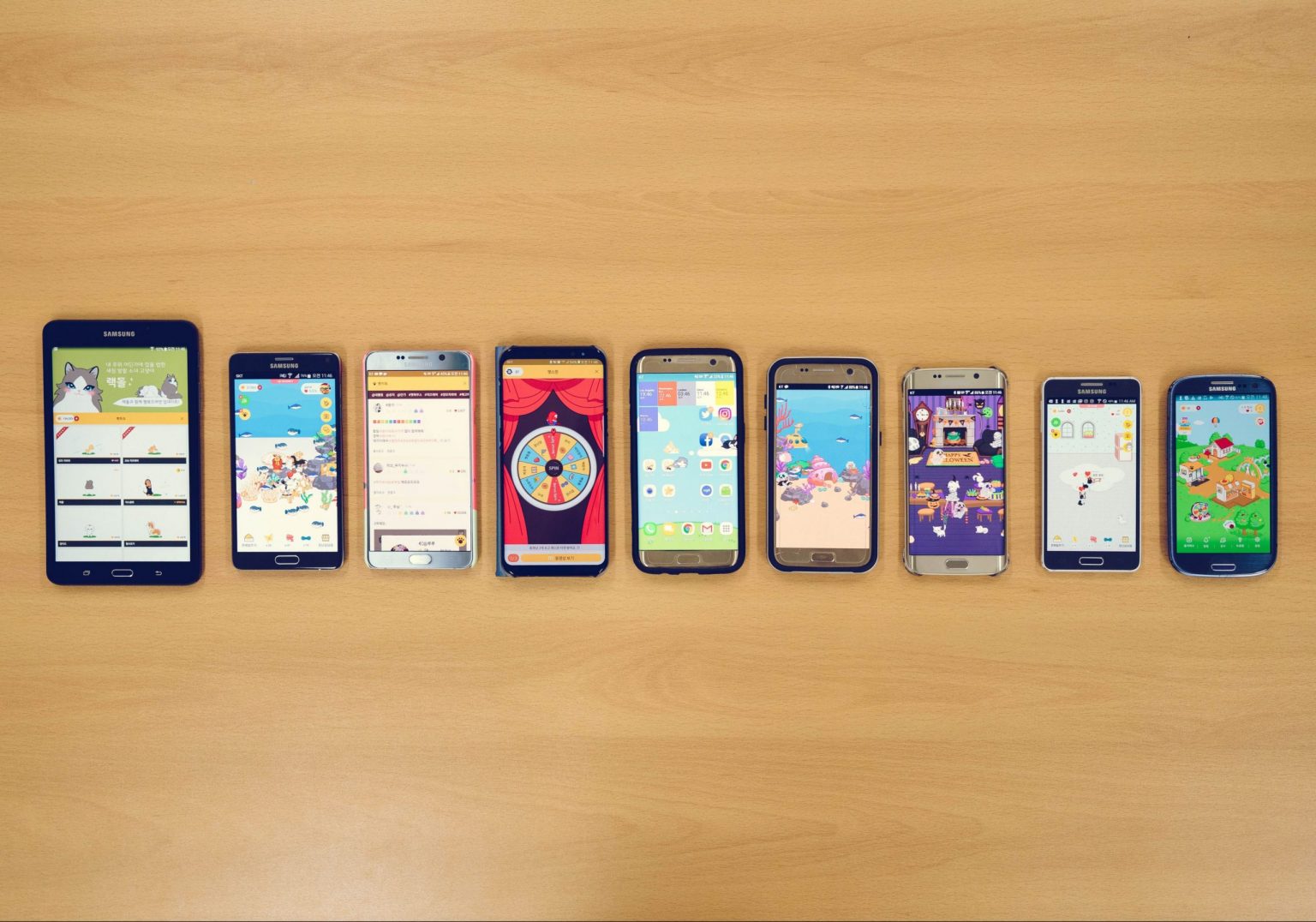

One thing to mention, when Hogyeong said “on your screen,” he meant on your home screen. One of Hellopets innovative features was to make use of the ‘overlay’ layer built into Android—the mobile OS that Hellopet debuted on. This meant that you could play with your virtual dog, cat (or macaque monkey) as they skittered over your clock, calendar and any apps you have scattered about. This effectively converted an Android phone into a more familiar virtual pet like the Tamagotchi.

But it’s much more now that AI and social technologies have come as far as they have.

Beyond simply acting as receivers of our care, Hellopet’s animals interact with the user in a way that’s similar to a digital assistant, albeit without the stiffness. Hogyeong explained how that aspect of the experience was crucial to Hellopet to the point pets had their personalities meticulously written with authentic and nuanced interactions to serve the app’s original Korean market. These were then localized by native speakers for the English, Chinese and Russian versions.

On the social side, Hellopet also has its own in-app social community called Pet Chat where users share memes, drawings or pictures of their real pets like they would Facebook.

To be fair, if you heard that experience described to you, your first reaction might resemble the one you’d use for unsolicited pop-ups on your web browser. If not, you might still write it off as yet another distraction to add to the list, one that’s profitable for a company like Applepie Studio.

But as we continually assess our changing relationship with technology and how updates on old models might affect that, it’s worth playing devil’s advocate and seeing the upside to a virtual pet app.

The variety of collectible pets includes chameleons, hamsters and even river dolphins

Different Breeds: Virtual Pets & Mobile Games

I started this story off with the Game Boy because if you’ve never had a virtual pet before, the comparison with games is all but inevitable and your skepticism of virtual pet apps would be warranted. The timing is extremely convenient for virtual pet apps—and potentially profitable. Like virtual pet apps, mobile games have piggybacked on the role of the smartphone in our lives now that it’s reached its peak.

Years before, someone who kept multiple gadgets would have carried some combination of a phone, an iPod, a digital point-and-shoot and maybe a handheld gaming device. If you were a student based in Asia, you might also carry around an electronic dictionary for language studies. It goes without saying the smartphone has gradually taken over the roles of all those dedicated devices—and absorbed their importance too: Losing a single phone is now the equivalent of losing multiple devices, and that’s why your phone is firmly glued to your person.

Many apps offer daily check-in rewards to incentivize regular usage.

This is one of the key reasons why the mobile games industry has been able to explode. No longer the exclusive pastime of stanky geeks huddled in their parent’s basement, games can be enjoyed by anyone capable of holding a smartphone and of being bored for ten minutes.

But in my books, virtual pets don’t prey on your smartphone addiction in the same way that other non-utility apps like games do. Here’s why.

Most current for-profit smartphone games are built with a “stamina” system. This means whether you’re building a farm, solving candy-coated puzzles or waging war on other players, how many actions you can make—that is, how much you can play a day is limited by some arbitrary unit representing energy.

The second game mechanic is that some actions aren’t instantaneous. I’m just making this up, but I’m sure there’s a bakery game where it takes you 1d 12h 30m to bake a solid gold loaf of rye. Don’t have the patience to wait for that? You’ll spend premium currency to speed up the process, which in this case could be called hearts, crystals or “bags of flour.”

For good measure, let’s say that in this game, you have to outsell competing bakeries that are also constantly trying to outsell you or burn down your shop. But let’s say you’ve become addicted to this game and you’ve used all your stamina for the day and your premium currency. Or maybe you want an instant advantage over your opponents. What do you do?

Pull out your credit card.

These boosts or top-ups are known as “micro-transactions,” which is a bit of misnomer because some of these value packages can cost upwards of $100 USD. This profit model is so popular, it’s since spread from smaller mobile developers to the big dogs of the video game industry such as EA and Blizzard.

By comparison, virtual pet apps like Hellopet and similarly popular cat-collecting game Nekoatsume, have cookies and goldfish as their respective premium currencies. But the important distinction here is that developers of mobile games use our sense of competition and completion to make these real-world purchases enticing (or all-but-necessary if they’re feeling greedy). With virtual pets, on the other hand, they typically only buy you vanity items: they don’t allow you the opportunity to fast-track your way to victory. The only “victory” to be had with virtual pets simply means a bigger collection of pets and toys.

In short, the premium items are just as they should be, a means to a premium—but not essential—experience.

Unlike many mobile games, the premium currency in Nekoatsume are used to buy purely decorative items.

So What’s Left?

At its most basic premise, virtual pets can be a momentary escape from the stresses of the modern world much like games. But, if profit and competition are non-issues for the average user on a typical virtual pet app, then all that’s left is their original intended function: an alternative to real pets.

According to Dr. Greg Fricchione, director of the Harvard-affiliated Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine, there are obvious psychological benefits to pet ownership, especially security and validation. In his words, “No matter what you do or say, your dog or cat accepts you and is attached to you.” And for your part, having a routine of caring for something can certainly be therapeutic.

A virtual pet by comparison isn’t too different, albeit it’s largely designed—programmed, in fact—to like you. And this unconditional affection is why I’d argue the virtual pet has continued to evolve and come back into our lives time again in new forms. They provide a low-stakes interactive alternative to the morass that is our social media-infused lives where the instant comfort of connecting to friends and family could also be offset by other symptoms of FOMO and a sense of inferiority when we only see everyone’s best moments.

As with the first Tamagotchis, the next generation of virtual pets still has a role to play in the lives of people who love animals, but can’t own real pets because of allergies or other personal situations. But they may also become the unlikely but fitting solution to lives increasingly alienated by technology. In short, becoming virtual pet owners might just give us back the sense of ownership we’re losing.

Notes: Virtual Pets Return to Form

- Handheld Collectible Rock invented by advertising executive Gary Dahl, Pet Rocks were smooth stones from Mexico’s Rosarito Beach.

- Sold as collectibles and marketed as “pets” with custom cardboard boxes complete with straw and air holes, as if for a real animal.

- By 1976, Dahl sold 1.5 million Pet Rocks for $4 each.

1996 — Tamagotchi

- Digital Virtual Pet Keychain created in Japan by Aki Maita. Tamagotchi is a portmanteau of the Japanese tamago for “egg” and the English “watch”. It was responsible for initiating the digital pet craze of the ‘90s and early 2000’s.

- “Grew” and required care in real-time.

- At its peak, 15 units were sold every minute in the U.S. and Canada. Capitalizing on millennial nostalgia, Bandai has just re-released it in its six original colors.

1997 — Digimon

- Digital virtual pet also created by Bandai. Digimon (short for “digital monster”) was intended as the masculine counterpart to the Tamagotchi, despite being popular for both genders.

- Digimon were distinct for being trained to evolve and fight, and were supported by franchising efforts like animation and video games.

- The franchise remains popular to this day, but obviously not as much as Pokémon, although it continues to compete with that franchise through animation and video games.

1998 — Hey You, Pikachu!

- Nintendo 64 Video Game. “HeyYou Pikachu!” emphasized caring for the iconic Pokemon rather than training it to fight. It was also one of the first 3D virtual pets.

- It was one of only two games to rely on the N64’s Voice Recognition Unit to communicate with the pet.

- The game was poorly received with some critics noting the voice unit was calibrated to accept only higher pitched child-like voices and not those of kidults.

1998 — Furby

- A toy robotic pet. The Furby was a toy robot developed by Dave Hampton, Caleb Chung and Richard C. Levy, the latter of which brought the toy to Tiger Electronics, which had previously created Giga Pets to compete with Tamagotchi in the U.S.

- Furbies came out of the box speaking a fictitious language called “Furbish,” but eventually “learned” English by replacing their Furbish phrases with pre-programmed English ones as they “grew.”

- During its first three years of production, over 40 million units were sold. The demand drove resale prices to over ten times their original retail value. For some reason, in late 2016, The Weinstein Company announced it would be producing a feature-length Furby film with Hasbro.

1999 — AIBO

- A toy robotic pet marketed as an “entertainment robot.” The first consumer model of Sony’s AIBO (Japanese for “pal” or “partner”) was released in 1999 with new annual models emerging until 2005. It was developed by engineer Dr. Toshida Doi, who enlisted his friend artist Hajime Sorayama to design the robotic dog’s body.

- Able to understand 100 voice commands, the AIBO did not necessarily obey them and would mimic a puppy before “growing up” into a mature dog.

- Sony announced it would discontinue the AIBO in 2006 to keep the company profitable, but in November 2017, Sony announced it would soon be releasing a new AIBO with an updated look and enhanced AI.

1999 — Seaman

- Video game released for the discontinued Dreamcast 64. Seaman was a bizarre virtual pet game where players raised a creature resembling a fish with the face of the game’s producer Yoot Saito. Like Tamagotchi and Hey, it required the player’s constant attention in real time to survive and also used voice recognition technology.

- The game has a negative or cult-like status because of its eccentricities, but it was also the third best-selling Dreamcast game of the time in Japan as of 2004.

1999 — Neopets

- A children’s website originally launched by Adam Powell and Donna Williams, the website introduced exploration elements beyond caring for pets and training them to fight such as building a virtual home and running a virtual shop. It was also notable for having two currency systems, with Neopoints earned by playing mini-games and Neocash that could be bought with real money.

- Neopets is consistently one of the stickiest sites for children’s entertainment. It is also notable for its use of immersive advertising (sponsored content directly integrated into the game’s universe).

Late ‘90s — Cabbage

- A canceled video game intended for the Nintendo 64 Disk Drive peripheral. Cabbage was developed by a team of Nintendo’s biggest talents including Shigeru Miyamoto, creator of iconic series like Mario and Zelda. As per its title, the game involved raising a pet “cabbage” that required real-time care.

- Intended features included the ability to “bring” the pet to other consoles by transferring it to a Game Boy. There were also plans to release extra content on low-cost discs that would develop the cabbage in different ways and that could be bought at convenience stores (the beginning of microtransactions).

- Though it was canceled, many aspects of Cabbage went on to influence other popular Nintendo titles including Animal Crossing and Nintendogs.

2005 — Nintendogs

- Video game for Nintendo DS. It used both voice recognition and the console’s touch screen to interact with the pet and teach it to do tricks. The game involved a point system to unlock more dogs and decorations for the player’s in-game house.

- Nintendogs used the NDS’s wireless networking capabilities to allow different players’ puppies to play together.

- As of March 31, 2015, all versions of Nintendogs combined had sold 23.96 million copies worldwide, making the series second the NDS best-sellers list behind New Super Mario Bros.

2010 — Kinectimals

- Video game for Microsoft’s Xbox 360 console. Kinectimals was used its motion-tracking Kinect technology to let players physically reach out to play with and “pet” the animals, all based on wildcats.

- Like the defunct Cabbage, Kinectimals also allowed players to transfer pets to and from handheld devices via the dedicated app for Windows phones.

- Kinectimals was well received, but like other virtual pet games for dedicated video game consoles, it now faces competition from newer or more portable virtual pet forms.

2010’s — The Next Generation

- As it stands, virtual pets have come full circle and returned to portable handheld devices in the form of apps on smartphones.The next generation of virtual pets will likely continue to be spread across different forms such as Nekoatsume for mobile apps, virtual reality-based video games like Fantasy Pets for the Oculus, or even new AI-enhanced robopets such as AIBO or robots specifically marketed for therapy such as Paro.