For someone facing a serious diagnosis, a comic book might be the last thing they would want to see, but it just might be what the doctor ordered—that is, if that doctor is Ryan Montoya. Both a practicing doctor and professional comic book artist, Ryan is a firm believer in the medium of “graphic medicine.” It’s a comic-based approach to storytelling related to the medical field, and their ability to break down walls between patients and medical professionals.

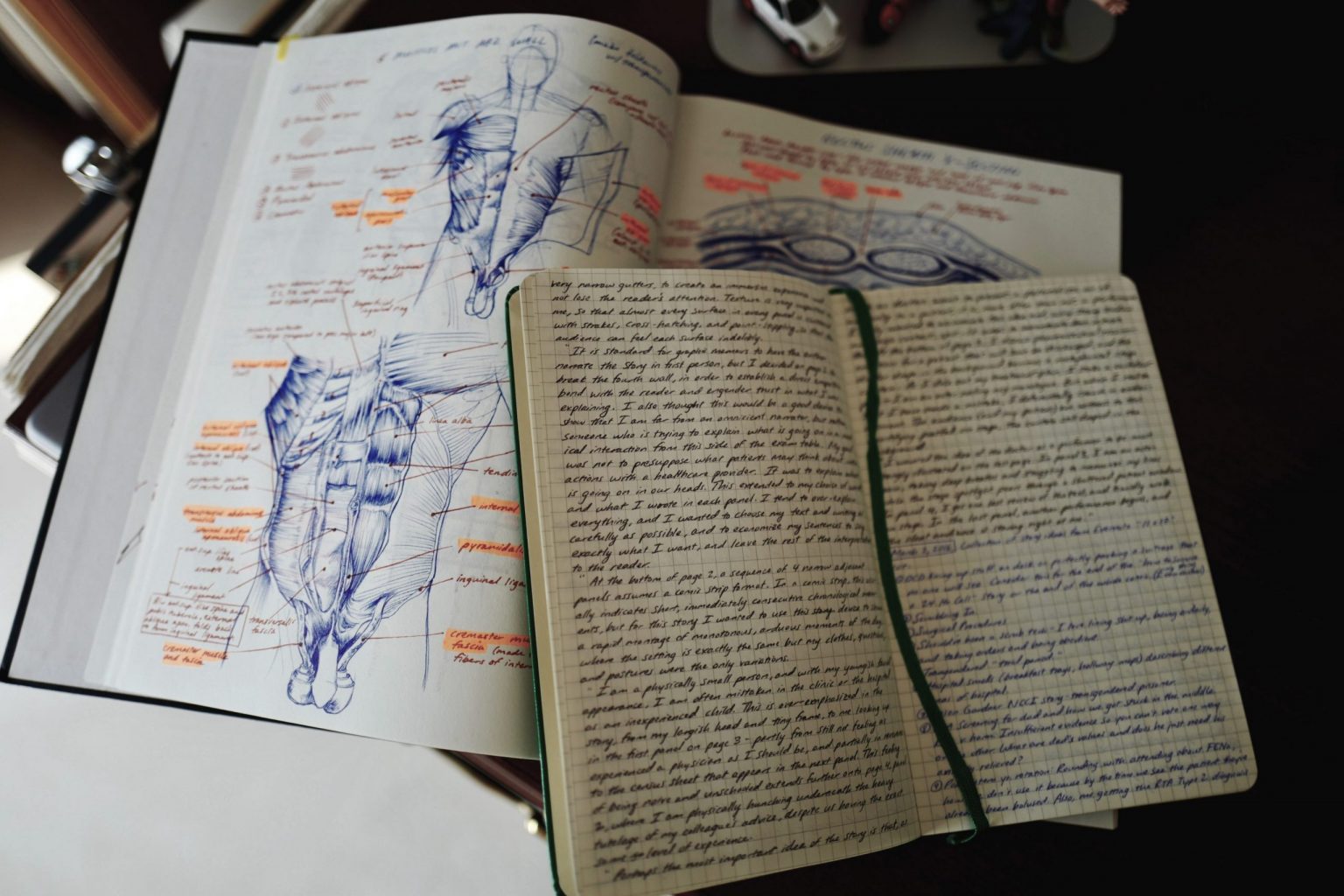

Pre-planning and anatomical sketches from Ryan Montoya’s notebooks.

“I think the focus on quality content first, where content or stories that are human, are never really going to go out of style. And whether or not we deliver it through voice narratives or through some kind of a different algorithm in the future, it doesn’t matter. We’ll find out whatever is the best avenue to tell that story in the first place.”

Streaks of color dominate the scene.

Speed lines depict supersonic motion.

The protagonist’s intent is clear.

As your eyes scan to the bottom page, a violent transfer of energy is captured in a moment as a swift punch lands a devastating blow on the jaw of a nefarious villain.

For those unfamiliar with the world of comics, this scenario—one straight out of our youth—is what we know best, a classic superhero narrative or one of the Sunday “funnies” in the newspaper. But for a growing crowd, there’s a much more layered and fascinating genre of comics that’s looking for respect.

A quote by author Jonathan Hennessey raised a great point about comics: “It always strikes me as supremely odd that high culture venerates the written word on the one hand and the fine visual arts on the other. Yet, somehow putting the two together is dismissed as juvenilia. Why is that? Why can’t these forms of art go together like music and dance?”

Comics deserve a new perception that isn’t overshadowed by its more popular entertainment-centric formats, and graphic medicine just might be the answer. In its simplest form, it’s medical subject matter told through comics, but don’t think for a second these are just the sterile illustrated cold-prevention tips you’d find in a pamphlet at the doctor’s office, not at Ryan Montoya’s at least.

Ryan is a practicing family doctor that trained in Massachusetts, focusing on opioid narcotic dependence. He’s also a professional comic book artist that’s been getting back into it, although he’d already worked in the industry for several years. He might be the hero to deconstruct existing prejudices against comics and thereby legitimize them for a very valuable purpose, even if people have trouble putting the two worlds together: “The combination of being a medical doctor and a comic book artist tends to throw people off,” he explains. “One of the most awkward questions I get, which is the most common question when you first meet someone is ‘What do you do?’” Depending who’s asking the question, Ryan either explains his entire admittedly lengthy story or simply states one profession or the other to save time, effort or awkwardness.

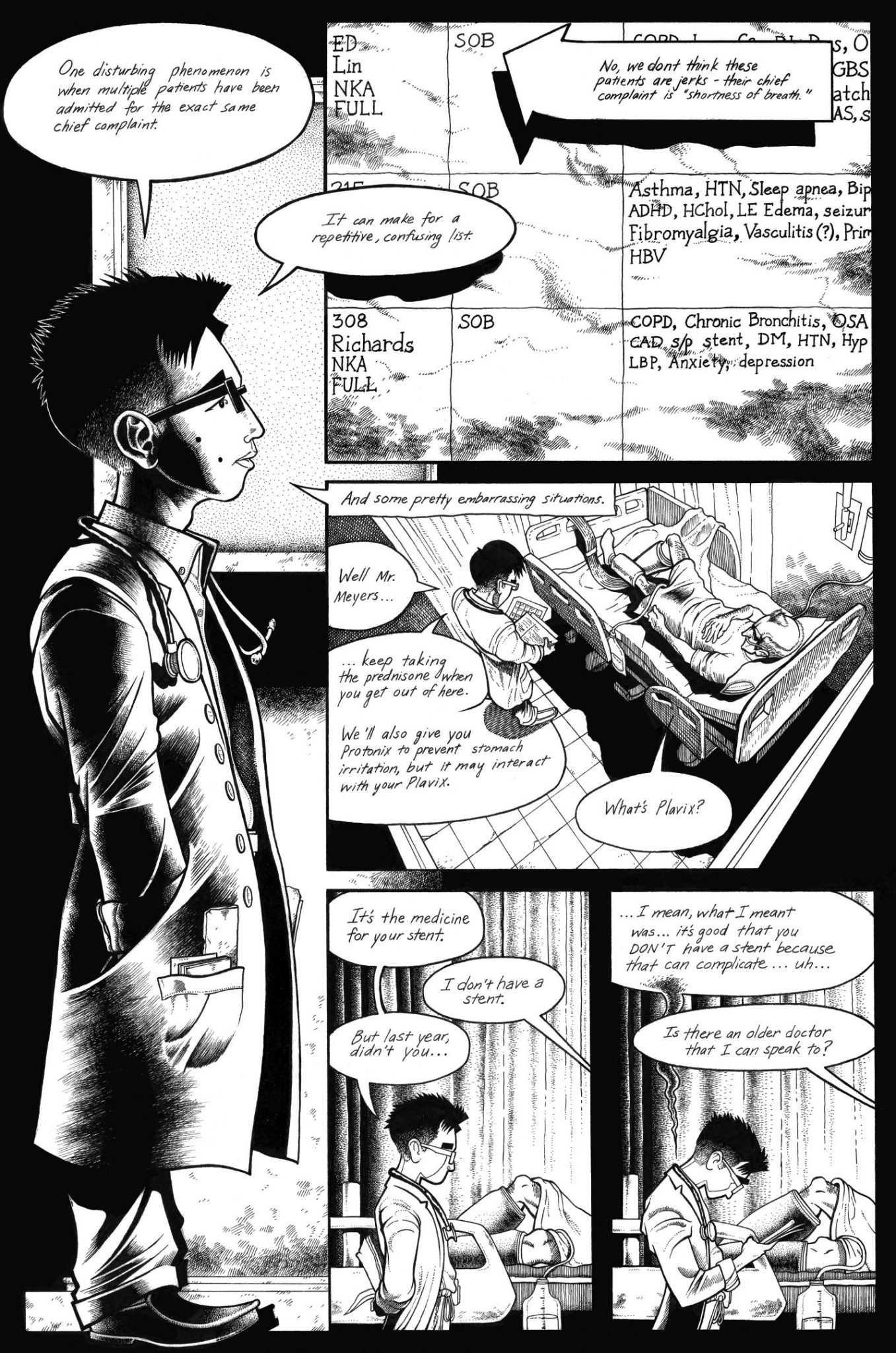

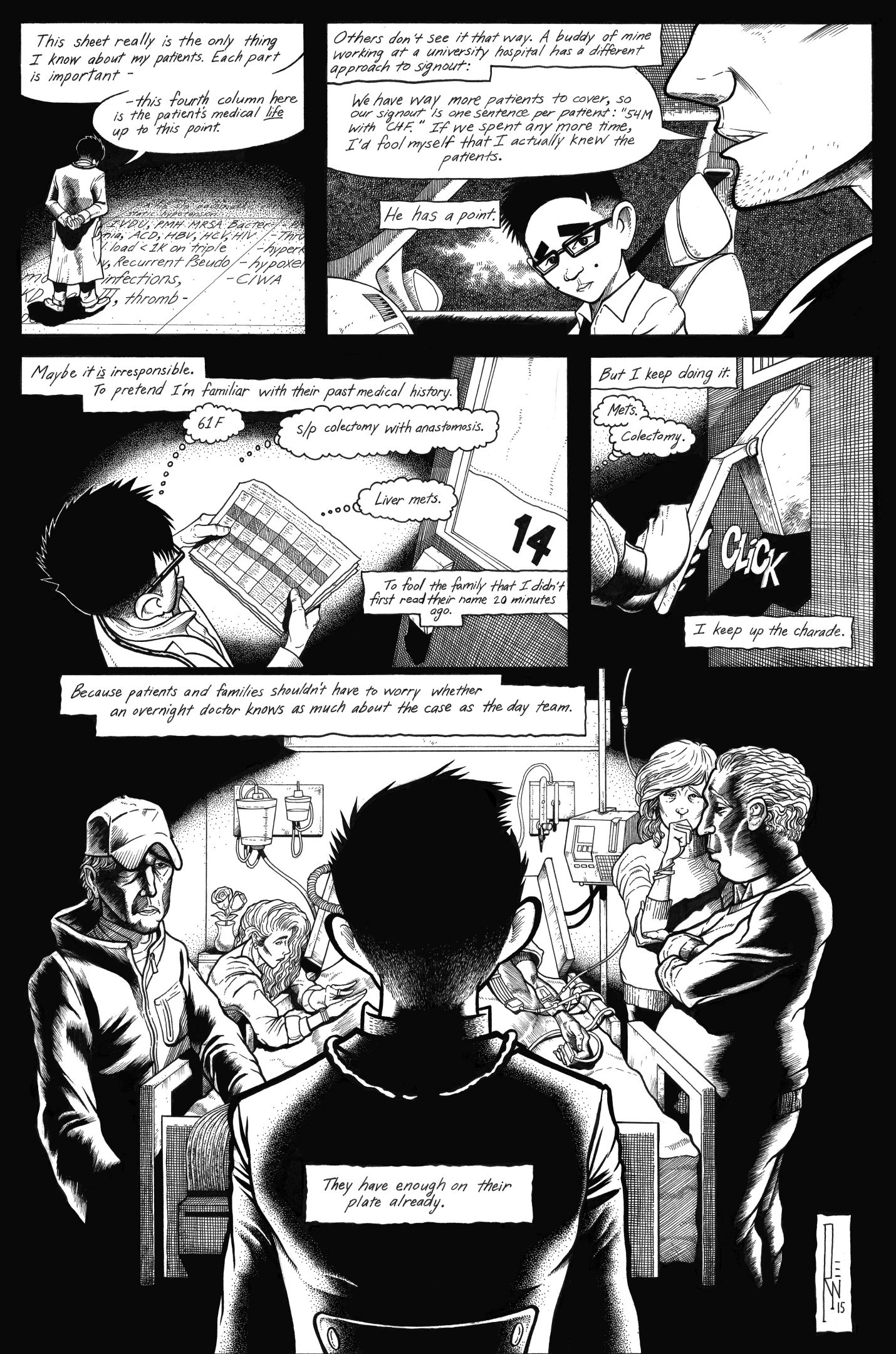

A page from Ryan’s Annals Graphic Medicine – Sign Out, featured in the publication, Annals of Internal Medicine. Published: Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):W141-W145 |

DOI: 10.7326/G15-0003 |© 2015 American College of Physician

Graphic Medicine is a relatively new genre of comics that was coined by Dr. Ian Williams in 2007 and was conceived as “the interaction between the medium of comics and the discourse of healthcare.” It came onto the scene after he recognized the potential of comics in the field of medicine.

That potential, Ryan finds, has unfortunately been limited by the mainstream market for American comics, which caters to the predominant stereotypical demographic made up of young, white heterosexual males. There is, however, a branch of comics that Ryan has always respected; the world of indie comics. “I think that the audiences have always been smarter and I think they’ve always had more to say,” he says, referring to the depth and quality that can be found in many independent and underground comics. “But because of because of this dichotomy between superhero and non-superhero it creates market forces that almost never favor independent comics.”

The lack of association between the two fields is understandable given where comics—specifically comic books—sit in the mainstream mindset. Today, they are still known for their vast imaginary worlds, intense emotions and epic battles. Although Marvel and DC and their pantheons of iconic super heroes and villains have explored deeper and more realistic topics to reflect their readership, their story arcs are still largely reducible to the age-old struggle between good and evil. For graphic medicine, on the other hand, there are rarely discernible heroes and villains, only patients, families and doctors, and only injury, illness and treatment.

Tapping the evocative strength of comic books while meaningfully informing the reader through graphic medicine can be challenging and it’s not just because of the status of comic books.

Medicine, according to Ryan, tends to be very dogmatic, which instantly puts it at odds with the creativity of comic books: “You go to medical school, you are taught how to do things. You may explore and kind of innovate in small ways, but to be honest, medical doctors are the mechanics of science. They are doing a lot of the grunt work. If the human body is a car, they’re the mechanics. Whereas science research, these are the guys who are innovating and coming up with new ways or new instruction manuals. So, it’s an inherently uncreative field, in my opinion.”

Overcoming or understanding that first hurdle leads us to the actual creation of art, but comic books might also limit the medium’s accessibility if they over-rely on an artist’s drawing abilities, which he finds is not necessarily the most important skill to have. “To me, the only price of entry to enter graphic medicine or to enter the comic book field, in general, is just to be a good storyteller. And that’s it,” he says. The importance applies regardless of who the teller is, even if they’re a doctor: “If you’re a good primary care physician, you can tell a story, and you can tell it at any level. You can tell it to another colleague in a matter of two sentences. You can tell it to a patient with less jargon in a matter of 10 minutes or an hour, or however long it takes to get that story across.”

The underground scene has chalked up some small victories, however, enough for fans to hope the genre gains a broader appeal down the line. Ryan cites the example of the Pulitzer Award-winning Maus by Art Spiegelman, one of the most well-regarded independent comics in history. It depicts the artist interviewing his parents about their experiences surviving the Holocaust. “Everyone who loved independent comics was like ‘yes, we’re finally legitimized! Like, this is it! We will no longer be considered the bastard child of comics and literature,’” he recalls, “…but we still kind of are.”

Graphic novels are still largely seen as more lofty artistic initiatives, and Ryan isn’t optimistic of any breakthroughs to recognition during this generation. Still, he believes people who love comics will continue to make them no matter what, but he also sees independent comics as fading like traditional publishing, despite enjoying a degree of stability after a long battle that’s been raging for decades.

Ryan’s Sign Out comic highlights the stressful procedure of sign-out in a medical environment.

“What happened in comics in the U.S. is they started growing up a little bit in the late ’70s. In 1978, there’s maybe the most well-regarded comic artist of all time named Will Eisner who invented what was called the ‘graphic novel.’”

For Eisner, the graphic novel was a pushback against how comics were seen at the time: as a lower and highly disposable art form with its artists valued accordingly. “So because of that, there’s always this context of comics being put in newspapers or in dailies, or in comic strips as kind of throwaway fare,” Ryan laments. “Get ’em done quickly, get cheap laughs and move onto the next serialization.”

Eisner’s introduction of the graphic novel or graphic narrative was helpful as a new marketing tool. Tired of doing comic strips, he wanted to do a long form story that was self-contained. He coined the term “graphic novel” to distinguish the work from comic books. For one, it removed the obvious angling of a Sunday comic and it also enabled other sub-genres to springboard towards greater credibility.

“A ‘graphic narrative’ is basically a comic book most likely about someone or something that’s real, a ‘graphic memoir’ is just a comic book about yourself, and ‘graphic medicine’ is just comic books about medicine,” he concedes. “And if I’m being like completely cynical, it’s a great marketing tool, and it’s just a great way for publishers to dig into a niche where they would never get any market traction if they were just saying ‘we’re pitching a new comic book.’”

While it might seem like an unavoidable practice of the business, the idea of pitching a graphic novel as a “graphic medicine novel” also gives a definable label for similar comics that have existed for a while, making them more marketable. “It’s a great way to kind of wrangle a lot of comics that have existed for decades that were about medicine, but now are just finding this umbrella term to reside inside,” says Ryan. “So basically, any comic books whether short or long form that have anything to do with medicine are considered graphic medicine.”

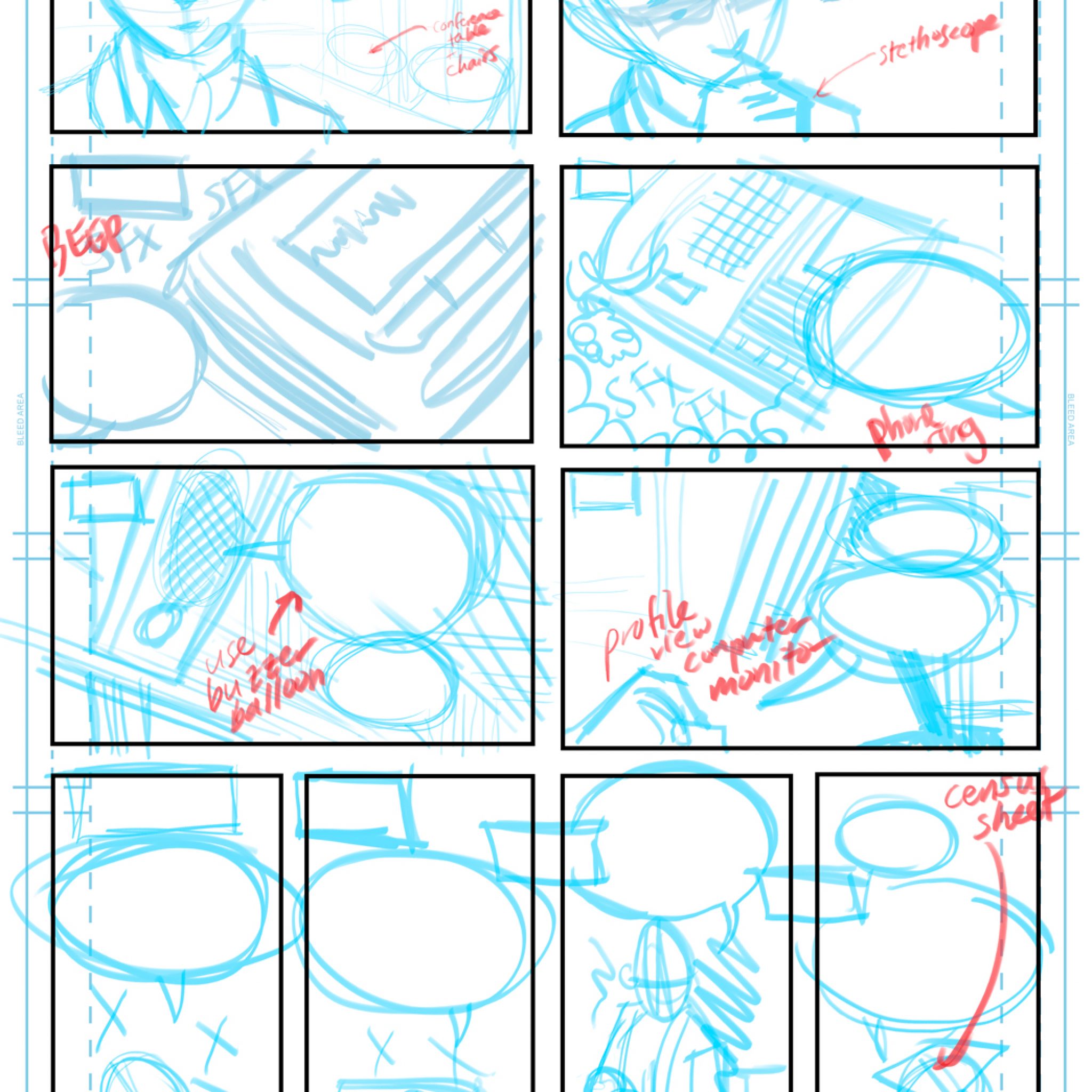

Early sketches.

The concept of storytelling with a graphic medicine novel isn’t confined to one perspective or method; it doesn’t need to simply be a first-person story of one’s illness or an instruction manual. Ryan describes graphic medicine as “a book or comic book form of an online support group.”

He cites the example of a few comics that illuminate or illustrate a relatable story to a patient with Lou Gehrig’s diseases. It’s here, he says, where the true value of graphic medicine and comics, in general, outshines any kind of instruction manual. “I think that what tends to be more compelling is a patient’s experience or being on one side of the medical provider’s table, and how scary or fun that can be.”

With the artist being able to manipulate the page and to create their definition of scale, perspective, and time, graphic medicine benefits greatly from the added depth. There are opportunities possible in comic books that simply aren’t available in literature or even movies. Ryan gives the examples of speech bubbles crowding around a central character, implying the dialog is suffocating them, or conversely, completely open panels devoid of those bubbles to denote quiet, contemplative scenes. “Sure, you can have movie scenes where the same things are happening,” he says. “But you really can’t express it visually the same way because you’re always bound by the same 16 by 9 ratio you have of a movie screen. You are not bound by that in comics.”

“Comics deserve a new perception that isn’t overshadowed by its more popular entertainment-centric formats and graphic medicine just might be the answer.”

And besides eliciting strong emotions in the reader with the unique visual qualities of the medium, medical comics books are powerful because they can be frank and simple to understand as well, something that is decidedly more important than overly technical or didactic instructions and advice from a doctor.

“There is this very real effect of every other thing that I say afterwards being kind of muffled out. It’s like the Muppets where you can’t even hear what is going on. It’s like mumbling noises. I’m saying all these technical words afterwards, and you do not hear a thing. And it’s because A, the terms afterwards are very hard to understand and B, you are still experiencing some other piece of information.”

The directness of comics can also facilitate how we convey difficult information such as giving a terminal diagnosis to a patient.

In both instances where a patient needs time to process what’s been said, Ryan believes graphic medicine and comic books offer a comfortable alternative where they permit them to physically slow down time and spend as much or as little time as they wish with the comic book: “That in and of itself is a value greater than if you just bring a tape recorder to a doctor’s visit, and you keep replaying the same words over and over again, and you have no clue what the doctor is talking about.”

The issue is particularly exacerbated in the case of specialists, who are often unable to properly inform patients. “The problem a lot of times with specialists—and I’m not saying every single one, but a lot of the ones I’ve worked with—is they have no fucking clue how to explain what is going on to a patient,” he puts it bluntly.

“You have certain types of vascular surgeons who work on only one type of blood vessel in the body of the hundreds of types of blood vessels, okay? When they are stuck in that field, how on Earth are you going to explain it to a patient? You know some super specialists can explain it to patients, but most cannot. And I think if you’re a good primary care doc you should be able to explain anything to everyone.”

His standards for communication reflect his goal with graphic medicine: he wants to humanize and improve the patient-doctor relationship. To start, he wants to balance out perceptions of the medium to create a better understanding of the doctor’s position: “I want with my comics to be almost exclusively an explanation, from my point of view, of what it was like specifically to train, how difficult it was, and how if you see a doctor at a certain point and you think you had the worst interaction ever, it was almost certainly as bad for the doctor as well but for completely different reasons.”

By depicting the struggles of both doctors and patients side-by-side, he also wants to deconstruct the traditionally paternalistic and enigmatic image of doctors that puts distance between them and the patients they serve—like “Magician’s Secrets Revealed“, as he puts it. In the process, he hopes his comics will make people uncomfortable by realizing how far from the real answer the doctor treating them might be.

For how visionary and noble its intentions are, as well as those of its indie brethren, it’s a very lopsided battle for graphic medicine in a world where spandex-clad superheroes have a seemingly unbreakable grip on the market. Part of this is due in fact to the assembly line style by which many American comics are produced: “You get a script from some writer. He may, or she may do breakdowns of what’s going on in the story, and then you translate it as an artist into some kind of thumbnail sketch. You go over dialogue and then usually if you’re just a penciler, you’ll do the pencils, someone else will do the inks. Someone else will do the color, and someone else will do the lettering. And you put it all together and package it, and you send it off.”

With smaller productions such as those for graphic novels done by one person, there isn’t the luxury of such specialization, and often, the artist has to choose one role in particular. Ryan compares the struggle to American filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson (Magnolia, There Will Be Blood), who writes and directs his own movies. And with a smaller production such as a graphic medicine novel, there isn’t such a luxury of having more help available. “He has the problem of whether he wants his writer’s side to take over, or whether he wants his director side to take over. I’d say that’s a problem not just in graphic medicine comics, but of any independent comic.”

Ultimately, however, a successful graphic medicine story doesn’t come down to just great writing or visuals. It comes down to fulfilling its given purpose, which is often guiding the reader through a series of emotions, even if they include confusion; sometimes a story’s impact depends on a reader not fully comprehending a topic. “Now if a graphic medicine novel is attempting to open up a bridge between a patient and provider or to explain what it’s like to have acute kidney failure and it does it well then, it’s done its job,” Ryan begins. “But if the intention of the author is to say ‘no, this is supposed to be confusing because fucking kidney physiology is so confusing and also doctors don’t know the answers,’ then if it’s done well, the reader should hit that wall. The reader should say ‘oh my god, this is just as confusing to me as it is for the medical provider,’ and I believe that if any literature, comic or movie is done well, it’s done to accomplish whatever goal the author had in the first place.”

These moments where a powerful message or feeling seemingly lifts off the page and makes an impact aren’t limited to the patients. Ryan frequently derives inspiration from other authors who have accomplished those goals he spoke of. He recalls a powerful moment where another author’s story would influence is own real-life medical practice. Harvey Pekar’s Our Cancer Year describes the anxiety a patient faces before undergoing an MRI scan, one that many of Ryan’s patients’ experience:

“Some of my patients would be terrified of going into an MRI machine again because they’re claustrophobic and they don’t like that sound. “The way he described it was like ‘imagine huge magnets attached to a whisk and it’s beating just around your head,’ and they’re like, ‘that’s exactly what it’s like! That’s why I’m freaking out! That’s why I need Ativan before I go in for my next MRI!’ And to me, that was a small example of kind of this transcendent moment with comics for me personally. That’s what resonated with me, finding comic artists who just absolutely nail what they wanted to get.”

The genre has so much potential for revolutionary storytelling, but stacked against more commercially-viable narratives, chances for graphic medicine to gain significant exposure will decidedly be an uphill battle. But Ryan is optimistic about the genre and doesn’t think it’s stopping any time soon.

“I don’t believe it’s reached its cap as long as there are stories to tell of from healthcare providers or from patients’ families perspectives. I mean, that’s a well that I believe will never run dry unless people stop getting sick.”