High Times, —

once cannabis’ go-to magazine, is looking to maintain relevancy

Post Feature

Reading Time:

Minutes

On a cold Saturday last March, dozens of young men in sweatshirts and graphic tees came to Salem, Massachusetts, with wads of cash to see the first solo exhibition by Bob Snodgrass. The 73-year-old Snodgrass, who arrived wearing his signature tie-dye fisherman’s hat and lavender Lennon sunglasses, is widely considered the godfather of glass pipes and a delegate from a bygone era of stoner culture: a time of sharing joints, eating homemade pot brownies — and reading High Times magazine.

For decades, Snodgrass’ intricately crafted bongs were regularly featured in High Times. Just a few years ago, a Snodgrass exhibit would have been catnip for the publication. But it wasn’t until the show wound down, after a group of about 20 men bought their pipes and finished smoking around a communal table, that Ab Hanna, a High Times staff writer, casually stopped by.

Hanna joined the magazine two years ago, in the midst of a tumultuous era for High Times and weed journalism at large. Family owned and operated out of New York for decades, the High Times company was purchased in 2017 by private equity firm Oreva Capital for $42 million. The marijuana industry is in the rush of a legalization boom, and everyone from Barneys to Martha Stewart is lining up to get a hit. That includes the media.

In the last half decade, a fresh crop of cannabis magazines has flushed the market. Glossies like Broccoli and Kitchen Toke, which often embrace vaping and edibles over joints and bongs, are tapping into the wellness and lifestyle space, all the while distancing themselves from the old stereotypes of stoner culture — stereotypes that High Times has long embodied and embraced.

For the first time in its history, High Times magazine now has serious national competition in the marijuana space. To keep up, the company has to walk a thin line between appealing to a large, new — and increasingly female — audience without alienating its longtime readership. In its attempt to do so, High Times has hit some bumps. Over the past two years, more than half of the editorial staff, including veteran editors, was laid off or left, and company revenue has shrunk.

The irony for High Times is that in an era of weed acceptance and even legalization, the flagship marijuana publication finds itself in a more precarious position than ever.

For several months after the Snodgrass exhibition, I checked the High Times website to see what Hanna had written about it, but I never saw anything. Later, Hanna told me that glass art, once a mainstay of the publication, had become too niche. “It’s something I’d like to cover but… I pay attention to the data and the numbers,” he said. “And when I cover glass art, the audience doesn’t really respond to it.”

For decades, the High Times office in New York was, well, exactly how you imagined the High Times office would be. “The art director would do lines of coke in the art room, and people would be smoking in every corner… Talk about fog,” Steve Hager, a longtime editor, told the Nation in 2013. After Tom Forçade, the magazine’s founder, died in 1978, legend has it mourners went up to the World Trade Center roof and smoked a joint rolled with his ashes.

Left: High Times Editor in Chief Mike Gianakos. Photography: Chris Maggio

Right before the Oreva acquisition, the company moved its headquarters to Los Angeles, leaving just a small satellite office in New York, where the magazine is still run. The Manhattan branch now occupies a glass-walled corner in a co-working space called Alley in Chelsea. Before I visited, a spokesperson tempered my expectations: “Don’t be surprised that when you get in there, there isn’t weed everywhere.”

Cardboard boxes filled with the most recent magazine issue were scattered around the office. Though veteran editor Danny Danko told me that the company was making efforts to diversify the magazine’s content — “We’ve gone from art glass consumption devices and seed companies… to a lot more vape pens” — the cover that month was classic High Times: a potted marijuana plant still wired and tagged, like it had just emerged from a black market nursery. Danko’s desk was also proof that not everything had changed. It featured a few bongs — one in the shape of a snowman — and a can of Febreze.

Founded in 1974, the first cover of High Times featured the portrait of a woman wearing a sun hat, her lips parted in curious pleasure as she considers a single mushroom held up between her ring finger and thumb. Forçade, a pot activist, founded the magazine in a Greenwich Village basement and fashioned it after Playboy. He wanted to prove that weed itself could be sexy, and to this day, each issue features a centerfold close-up shot of a bud strain in psychedelic colors. “The reason he started the magazine was not to make money, but basically to give a middle finger to the man,” says Bobby Black, a journalist who worked at the magazine between 1994 and 2015. “It was irreverent. It was bold.”

Within just a few years, the magazine became a cultural touchstone, moving 500,000 monthly copies. After a misguided — and embarrassing — foray into cocaine coverage in the 1980s, High Times rebounded in the ’90s under editor Steve Hager, who ushered in an era of experimentation and investigative stories. “It sold like hotcakes because every issue had stories about deep politics and little-known counterculture history,” Hager wrote me in an email.

The early years of the internet proved fruitful for High Times. The magazine rushed to launch its website in 1995, after staff saw that the magazine’s rival, Cannabis Canada, was already online. “Finally! Somewhere you can relax, light a phattie, and enjoy the atmosphere,” read the site’s welcome line. Visitors could pick up merchandise from Planet Hemp, a High Times–owned store, and vote on their favorite pot-themed cartoons. “We’ve got all the space we need!” the site read. “So who got the weed?!”

But the company began to fray in the early 2000s. John Mailer Buffalo, Norman Mailer’s son, came on as the executive editor amid the first of many editorial firings and turnovers. Buffalo tried to pivot the magazine, unsuccessfully, toward a broader readership. “It was a big mistake,” says Steve Bloom, a former editor. “The readership didn’t like it, and it’s never really come back from that time.”

The website also began to struggle and soon became little more than a repository of dated magazine stories. Even by the early 2010s, the staff still had not quite yet remastered the internet. They teased the first page of a magazine article online, hoping it would entice readers to buy the magazine off the stands, and they were late to delivering more service-oriented content.

After the passing of the magazine’s longtime chairman and legal counsel in 2016, “the company went into a complete downward spiral,” Bloom says.

David Kohl, a tech and media adviser who had previously worked at more corporate establishments, such as Viacom and Nokia, was hired as the president and CEO in 2015. Former employees say the culture of the magazine shifted dramatically, and the tight-knit familial atmosphere disintegrated. Meetings became closed-door. There was a crackdown on staff who liked to sneak into the stairwell to smoke pot during work hours. “[Kohl] was focused on bringing in other suits. He wanted to bring in money,” Black says. “It became a ‘this is a company, this is a brand, and if you don’t like it, there’s the door’ kind of thing.”

Kohl was fired after six months and sued the High Times company for $6 million in damages. In court documents, Kohl alleged he was terminated for trying “to alter the culture of unprofessionalism.” The lawsuit is still pending. Kohl did not return requests for comment.

For High Times, that might not be so easy. As editor in chief Mike Gianakos put it to me: “We really are about pot and pot smokers.” Verena von Pfetten, co-founder of Gossamer, which aims to appeal to the occasional or casual pot consumer, says that High Times has a well-defined identity. “High Times was an idea of a publication that focused really single-mindedly on the plant and cannabis and the industry,” von Pfetten says. “They are speaking to someone who is very, very well versed and passionate and focused on the plant and the industry itself.”

The new cannabis consumer isn’t necessarily a weed aficionado. Publications such as Gossamer and Broccoli are setting their sights on the young, casual marijuana consumer who considers lifestyle first, cannabis second. Or as Gossamer sums it up in its website’s tagline: “For people who also smoke weed.”

“I was certainly never a reader of High Times,” says Anja Charbonneau, the founder and editor-in-chief of Broccoli, which launched in 2017 and has a print circulation of around 30,000. “There was immediately a lot of creativity on the product and retail side, and yet you still have the same magazine that is super, super industry-focused and for people that are a 24/7 weed person.”

“High Times always came from this place [of] ‘We’ve done this the longest. We’ve done this the best,’” says Jen Bernstein, the magazine’s former managing editor. “There was a little bit of ego involved too.” That hubris may have blinded the publication to broader cultural changes.

For decades, High Times was a platform for legalization activism. But when recreational weed finally did become legal in some states, big money and Wall Street financiers came right on its heels. The monied transformation of the weed market — expected to reach $16 billion this year — and the cultural changes that came with it seemingly caught the magazine off-guard.

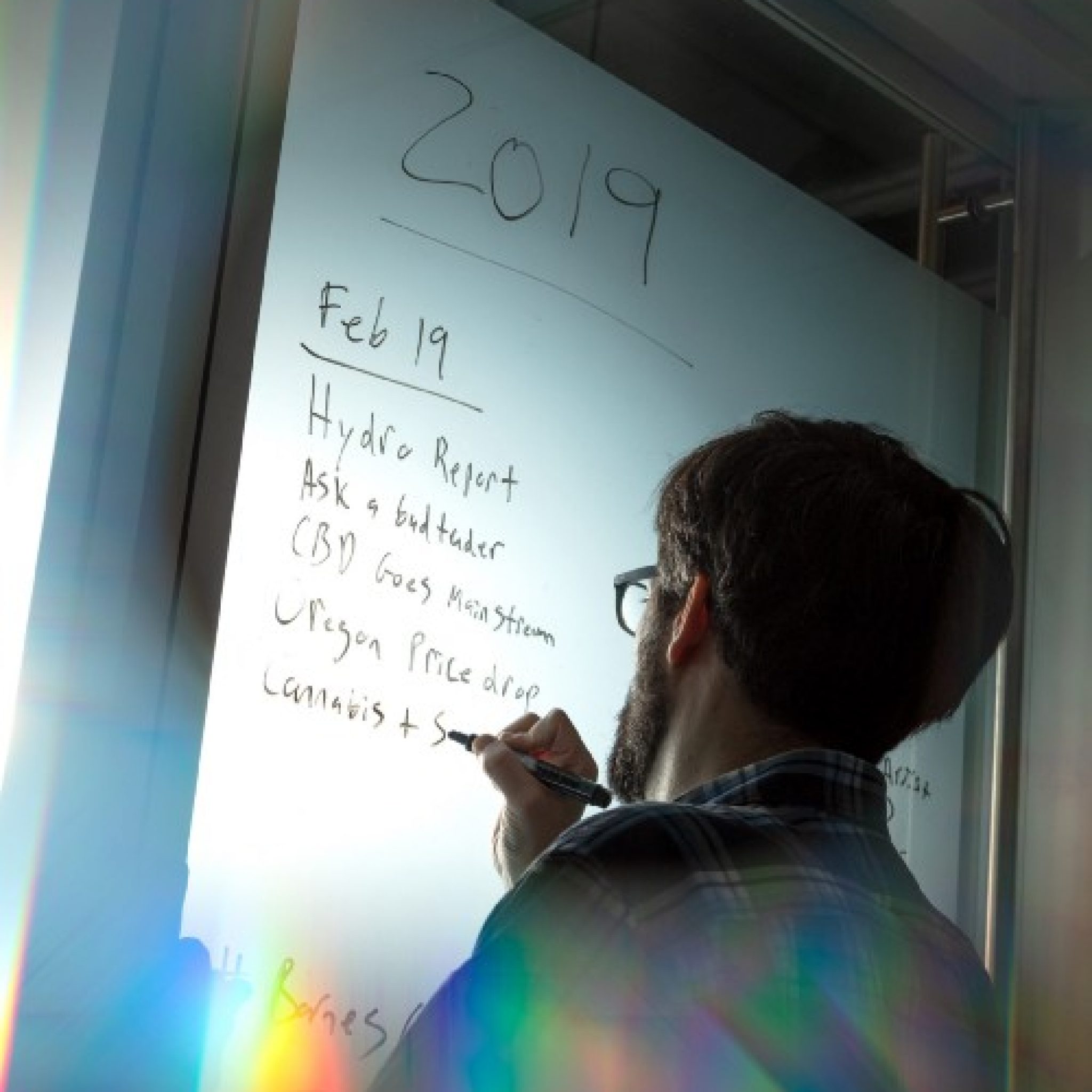

And you can see it in High Times’ editorial voice. A recent issue of Gossamer, for instance, featured essays about Babybel cheese and egg slicers. Meanwhile, High Times is still reporting on hydroponics and the state of cannabis extracts.

And the magazine has lagged elsewhere as well. In a wider media industry finally trying to improve gender diversity, the High Times staff has historically been male-dominated, which explains why its online readership is 74 percent male. That’s in contrast to Broccoli, where a majority of the readers are women, according to Charbonneau, the magazine’s founder. She says that the magazine’s visually pleasing features, such as a profile of a female candlemaker in Mexico City or an artist’s paintings of Hawaiian women, are bringing women into the market. Though current gender breakdowns of marijuana consumption in the United States are difficult to pinpoint, a recent survey by the Cannabis Consumers Coalition found that a “majority of respondents were women by over a 15% margin.”

Then there’s the aesthetic shift. Where the High Times visuals were once defined by slime-green fonts and Ice Cube in a cloud of smoke, modern weed culture can also include a pastel-tinged photo shoot of a cat in a beret with pink macarons for a piece on catnip dispensaries.

High Times hasn’t quite adapted. The magazine’s Instagram account — which has an impressive 2.4 million followers compared to, say, Gossamer’s 16,000 — is as stonery as ever, featuring closely cropped bud shots and weed memes. For Valentine’s Day, the account posted an unfiltered photo of a giant joint-smoking teddy bear with a plastic bag of marijuana nugs and a bong between its legs, captioned “Will you be my Valentine?”

Like countless other modern media companies seeking an advantage in a cutthroat landscape, High Times is leaning into its events business. The first annual High Times 100 gala was held last spring in a four-level nightclub in downtown Los Angeles, where the waitstaff served wine while attendees perused tables displaying vape pens. Well-suited men pulled joints from their inner coat pockets and lit up. The glitzy awards ceremony, which honors the most influential individuals in the industry, was an attempt to prove that the publication could keep up with the changing times. The evening “wasn’t necessarily what you’d expect from a so-called stoner event,” wrote Madison Margolin in L.A. Weekly. “But who’s calling it a stoner event anyway?”

Events have become a business focus for High Times since the Oreva Capital takeover — and for good reason: According to SEC filings, in 2016, High Times as a company made 68 percent of its revenues just from the Cannabis Cup, a global trade show, festival, and bud competition that started in 1988 in order to rate seed strains. A successful Cannabis Cup today can bring in 25,000 people, and there are multiple Cups each year — the company plans to throw 21 Cannabis Cups and festivals in 2019. High Times also runs Spannabis, an industry trade show in Europe, and recently established a new gala called Women of Weed.

Oreva has also fueled a slate of investments: High Times has acquired Dope magazine, Culture magazine, and Green Rush Daily. The company has also launched High Times TV, a video channel on its website. “Let me tell you, we’re just started,” Adam Levin, founder of Oreva and publisher and CEO of High Times, told me.

Levin told employees at the time of the acquisition that the expansion was part of an effort to take High Times from a “magazine to a multiplatform entertainment company.”

But behind the bluster, the company seems to be in some financial turmoil. Despite the acquisitions and High Times’ strong social media presence, the publication’s website draws only 4 million monthly visitors — compare that to Rolling Stone’s website, for example, with 23 million visitors. The company incurred net losses of more than $40 million from 2015 to the beginning of 2018. In the first three months of 2018, the company generated $2.7 million less in revenue than over the course of the same period in 2017. “[2018] was a tough year with the Cannabis Cups. It was tough to get regulated events done,” says Levin, pointing out that the company held no Cannabis Cups in the first three months of the year.

“There’s so much debt going on,” says Sean Black, a Cannabis Cup director who stepped down from the company last month. High Times plans to go public and is selling shares for $11 through a Regulation A+ IPO, an alternative type of offering that allows companies to crowdfund from the general public and not just certified investors. High Times needs to raise $17.2 million to get on the Nasdaq and has extended the deadline several times in an attempt to meet that number.

“I know that’s something High Times has been publicly struggling with — with mergers and debts,” says Charbonneau, the Broccoli editor. “I know I don’t want to build my company that way, because it’s not working.”

In recent years, there’s been high turnover at the magazine. About a dozen people were either fired or have left since 2017, including the head of content, the edibles editor, and the former editor in chief. A masthead from December 2016 lists 18 editorial staff members — the February 2019 issue lists just eight. Levin told me that since he acquired the magazine, only two people have been laid off, but several others were fired for various reasons.

“Once Oreva Capital came in and Adam [Levin] bought the company, they did a clean sweep of most of the creative,” says Katie Brown, a graphic designer who was fired in 2017. She says there was no budget to hire models or rental gear for the ambitious video shoots the new management wanted. “They would promise these sponsors all these grandiose packages, and we’d deliver them nothing, and we’d have to deal with the backlash.”

One editor who was let go says she didn’t have money to pay her photographers. Mary Jane Gibson, a lifestyle editor who left last year, says the management wanted the company to become a “leaner machine” and that “they were getting rid of full-time staff positions.”

Meanwhile, management was pushing for more content in an effort to broaden readership. “I was posting 12 to 15 stories a day online, not including magazine content,” says Emily Cegielski, a former director of digital media, who also left last year. Cegielski said the audience grew from its fringe base of stoners and college students to more mainstream weed users. “You could see the shift. It used to be mostly young men looking at our website, and there was a lot more women and older demographics, people looking for CBD.”

Many former employees lament the corporatization that’s taken place under Oreva. Since the takeover, the company has grown from 17 employees to 70, with most of those roles added in events and sales. “Everyone felt this impending doom of the corporate monster waiting for High Times, and now that’s what they are,” says a video producer who was laid off in 2017 and requested anonymity to avoid a potential lawsuit. “It’s a shame, because all these people I was with honestly were the authentic cannabis people, the real High Times.”

“Has the company tried to get rid of that stoner mentality and have adults at the table? Absolutely,” Levin says. “But this is still a family type of environment.”

Though these days, the magazine relies heavily on freelance writers, Gianakos maintains that the magazine is secure and points out that page count hasn’t shrunk. “We’re told it’s an important part of the company. It’s the flagship enterprise that we have, and sort of a calling card that we have,” he says. “At events and sales, the magazine is what people know as High Times first and foremost.” Despite the cuts, Gianakos told me that the magazine is “still operating at the same way we had been.”

Levin insists that High Times magazine will continue to grow alongside the industry, and that cannabis-infused wellness is a part of that growth. “We have a long way to go to produce the content I hope we’re producing, but we also want to stay true to our fans and community that we serve and to that hardcore user, that rabid user,” Levin says. He told me they were also hiring for High Times magazine, though the only editorial openings on the company’s website were for a multimedia editor for Dope and a media internship. When I asked what High Times jobs were open, Levin said, “If we find bright, talented people, we’ll make room for them.”

In the meantime, Gianakos says he’s prioritizing diversity in readership, staff, and freelancers to include more women and minorities. Out of the 21 staff listed on the masthead, only four are women, though Gianakos says he works with a number of female freelancers, including two currently working on a CBD story and a profile of Mila Jansen, the Hash Queen of Amsterdam.

He isn’t concerned about missing the wellness trend. To Levin, High Times taps into a niche area of the cannabis scene that nascent magazines like Gossamer can’t. “It’s the experience and the knowledge and the expertise that you would get from a publication that has been doing it for years,” he says.

But the magazine is trying to branch out. Recent features have included the best strains to smoke before sex, a chat with Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna, and a “Best of Instagram” roundup. Ads still show women in bikinis or vape pens as phallic objects, but Danko, the senior cultivation editor, says their ads now have “less skin” than before.

But the magazine isn’t abandoning its core readership. I asked Danko about an interview he and Gianakos conducted with Josh Kesselman, founder of a vegan rolling paper company, in the April issue. Kesselman is photographed wearing a onesie and lighting up a huge blunt on his couch. I wanted to know whether High Times thinks there’s space in today’s weed media landscape for this sort of content, which can feel like a throwback to an earlier, bro-ier era. “We’d be remiss not to shine a light on all that’s going on within the community and the industry,” Danko said. “I don’t think stoner culture is going away.”