There’s so much “stuff” in this world, physical and digital.

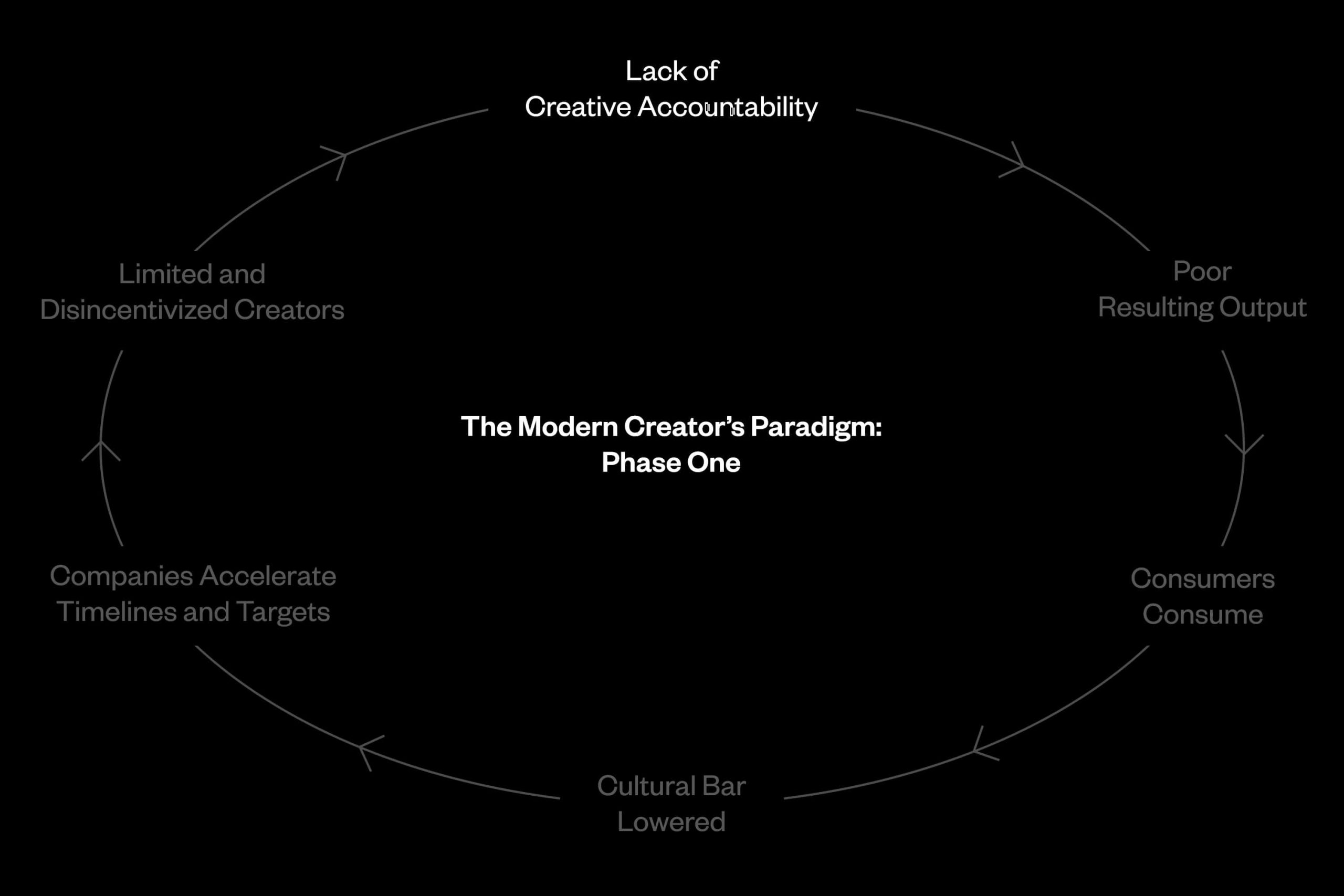

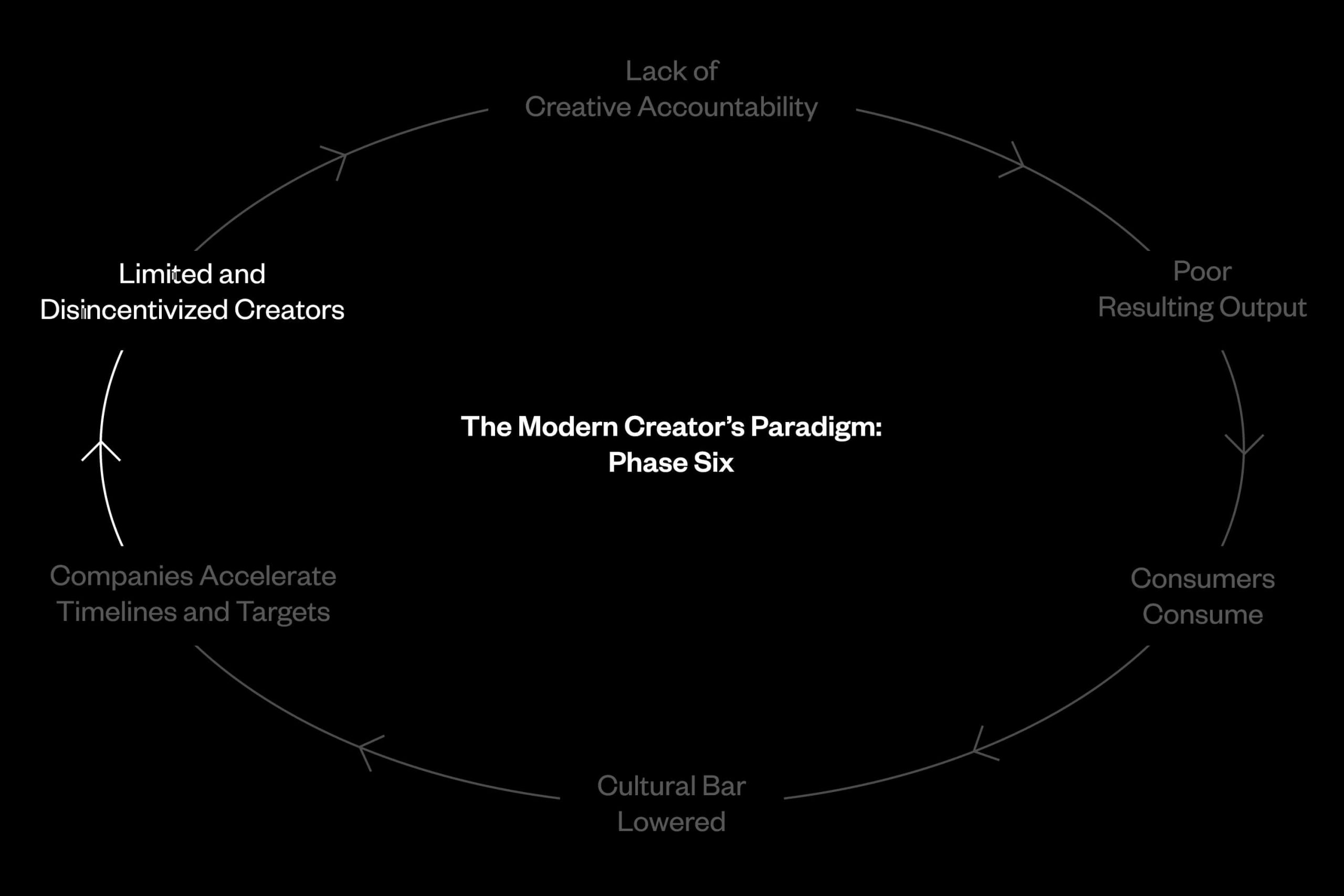

Media, consumers, and creators have unwittingly begun dancing a dangerous looping tango.

Rather than challenge each other to create new ideas and form new connections, all of the players in the business of media (which these days means everyone) have accepted the roles of producing and consuming “stuff.”

This is unsustainable and drastically diminishes the art of creativity.

Saying consumers play an equal part in this terrible dance is a loaded statement, but one that is worth unpacking.

The average production and consumption relationship results in environmental destruction, the faltering of grassroots initiatives, and the uncritical acceptance of existing practices.

All of these outcomes together have created a culture that is focused on the short-term—happy to live and die within the span of a generation, or worse, a single season. What is needed is a return to an infinite cultural mindset.

There is a clear overproduction of things (intangible and tangible) that have been created uncritically, unquestioningly, without needing to meet any type of standard other than existing.

New output is produced everyday due to the accessibility of tools for creation. Despite the existence of ever greater quantities of “stuff,” the output that might be of value gets lost.

We have grown accustomed to shutting off our critical thinking faculties. Critical thinking done by consumers and creators is necessary in order to locate the genuinely provocative, exciting work.

As a consumer, critical thinking means making sense of the things before you by making interpretations and analyzing through the frame of seeking a better quality of living. As a creator, critical thinking means making stronger connections with audiences.

Critical thinking in action by consumers and creators leads to output being respected and valued accurately, which pushes culture forward towards the infinite cultural mindset.

Panelists on a MAEKAN Session about criticism spoke about how society’s shift towards social media has lead to the disappearance of meaningful discourse surrounding new work and ideas.

While the dismantling of traditional gatekeepers has lead to a more democratic landscape, it has also lead to more surface-level conversations about work and tepid assessments of everything put before us.

We want to engage in harder conversations and assess the downward looping spiral we’re stuck in critically. This article sets out to establish clearly where we are now and hopefully find a solution to the modern creator’s paradigm.

Lack of Creative Accountability

We define creative accountability as holding all things created and released into this world to an exacting standard of having clear purpose and a reason for existence. Creative accountability ceases and we stop examining the making process, no longer require meaning from objects, and forget to bring value to consumers and culture. Creative accountability goes missing when critical thought falls out of fashion.

How did we reach this point? Within the last ten years, social media has become the dominant distribution vehicle and space for dialogue. The verbiage of “following” someone and being a “follower” carries with it positive connotations in the context of brand building. When you follow a person or brand, you do so out of personal, and most likely positive, interest.

You join a legion of other followers who are expressing this same personal interest. All of these people are communicating their individual sense of self through the content they’re consuming. This social construct—that everyone following an account is expressing an interest that is a part of their publicly portrayed identity—means that dissenting opinions are squashed.

Challenging statements and questions are not welcome because the suggestion that something is amiss with the content being shared throws into question all of that account’s followers taste and identity.

This problem is compounded by media entities within industries neglecting to hold creators accountable.

Media has unquestioningly supported the voices of individual creators by buying their influence with money or access. In order to keep the press trips, swag, and ad dollars coming in, creators keep telling the same positive (read: shallow) narratives.

Media, in order to keep exerting influence on niche audiences through individual creators, have no incentive to demand those creators to meet any type of standard, as they come pre-packaged with an enrapt following.

Esteemed trend forecaster and critic Lidewij Edelkoort summed up the current state of media in her 2015 Anti-Fashion Manifesto, writing, “The genial humour and knowledge of some of the best fashion journalists at international newspapers is rapidly replaced by uninteresting generalizations by a younger generation, articles that are opinion pages instead of critical assessments from a professional point of view. The Facebook culture of ‘likes’ has engendered a writing culture of liking, where new proposals are welcomed like lifesavers…”

“The genial humour and knowledge of some of the best fashion journalists at international newspapers is rapidly replaced by uninteresting generalizations by a younger generation, articles that are opinion pages instead of critical assessments from a professional point of view. The Facebook culture of ‘likes’ has engendered a writing culture of liking, where new proposals are welcomed like lifesavers…”

—Lidewij Edelkoort, 2015 Anti-Fashion Manifesto

The Instagram account @insta_repeat satirically mocks the preponderance of formulaic photos on the platform. The eerie similarity in photos from different accounts haven’t prevented those creators from building followings numbering in the hundreds of thousands.

Without creative accountability, any type of visual output or new ideas that find some measure of success are copied and reproduced endlessly with very few people daring to suggest that some more consideration is necessary.

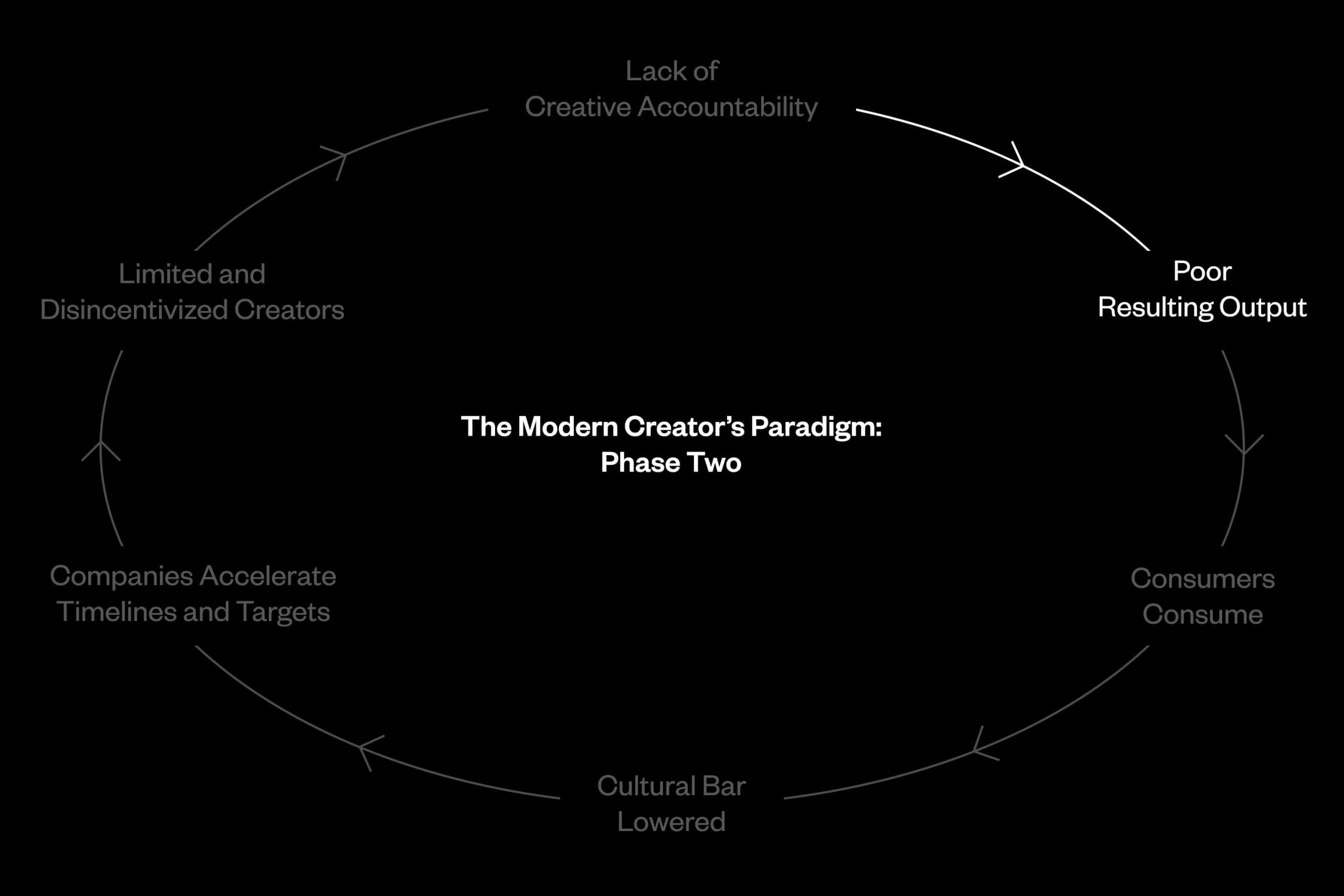

Poor Resulting Output

When there is no creative accountability, low quality output becomes the new baseline and is continually validated by the output. The democratization of tools, access, and distribution has created a world of overwhelming output that merely satisfies the most recent, lowest standard.

From the worlds of high fashion to direct-to-consumer branding, from restaurant websites to meme accounts, everything starts to look and sound much the same: quickly produced, with little deliberation, and fitting in neatly with everything around it.

Overall process democratization has enabled many people to ideate, create, and publish their visions in a matter of seconds, minutes, or hours. Many of the people making and showing their work today are able to because of relatively affordable and accessible tools—a basic smartphone and an Internet connection are all that’s needed to make something and show it to the world. However, without creative accountability, the new work that’s generated rarely gets the critique necessary for it to develop into something refined and of higher value.

At the same time, luxury brands and well-established companies see society’s lower standards for objects as an opportunity to generate sales. Rather than engage in creative accountability to elevate output, they produce “premium mediocre” goods to take advantage of the situation.

All of us are now regularly viewing, digesting, and buying average to below-average content; in contrast, things of remarkably greater quality surprise us rather than strike us as being the norm.

Eugene Rabkin, writer and founder of stylezeitgeist.com wrote on this subject, “the underlying point of the factors outlined above is that premium mediocre feels good, even if this feeling is fleeting and illusory. We’ve all fallen for it. As a matter of fact, fashion probably wants us to feel that way, so next week we can go out and buy premium mediocre again.”

As creators, we are unconsciously conditioned to produce what we are “able to get away with,” and as consumers we increasingly blindly accept the product of that mentality.

“…the underlying point of the factors outlined above is that premium mediocre feels good, even if this feeling is fleeting and illusory. We’ve all fallen for it. As a matter of fact, fashion probably wants us to feel that way, so next week we can go out and buy premium mediocre again.”

—Eugene Rabkin

Consumers Consume

This is a natural part of the cycle. Consumption doesn’t stop. New creators start making fresh work everyday with varying degrees of knowledge around the history of whatever they’re making.

New consumers start buying these goods with varying levels of research into the items and their origins. The constant tracking of purchases and media consumption seems to signal that things are working—people continue to buy, interact with and like things.

Consumption is an unchanging part of this cycle (short of serious global natural disaster, nuclear war, alien invasion etc.), but the way in which consumption occurs is affected by all the other parts of this cycle.

Today’s end customer benefits from access to marketplaces galore. E-commerce options and secondary markets show that consumers and creators have prioritized convenience and cost over genuine desire and interest, leading to a frictionless but ultimately soulless experience.

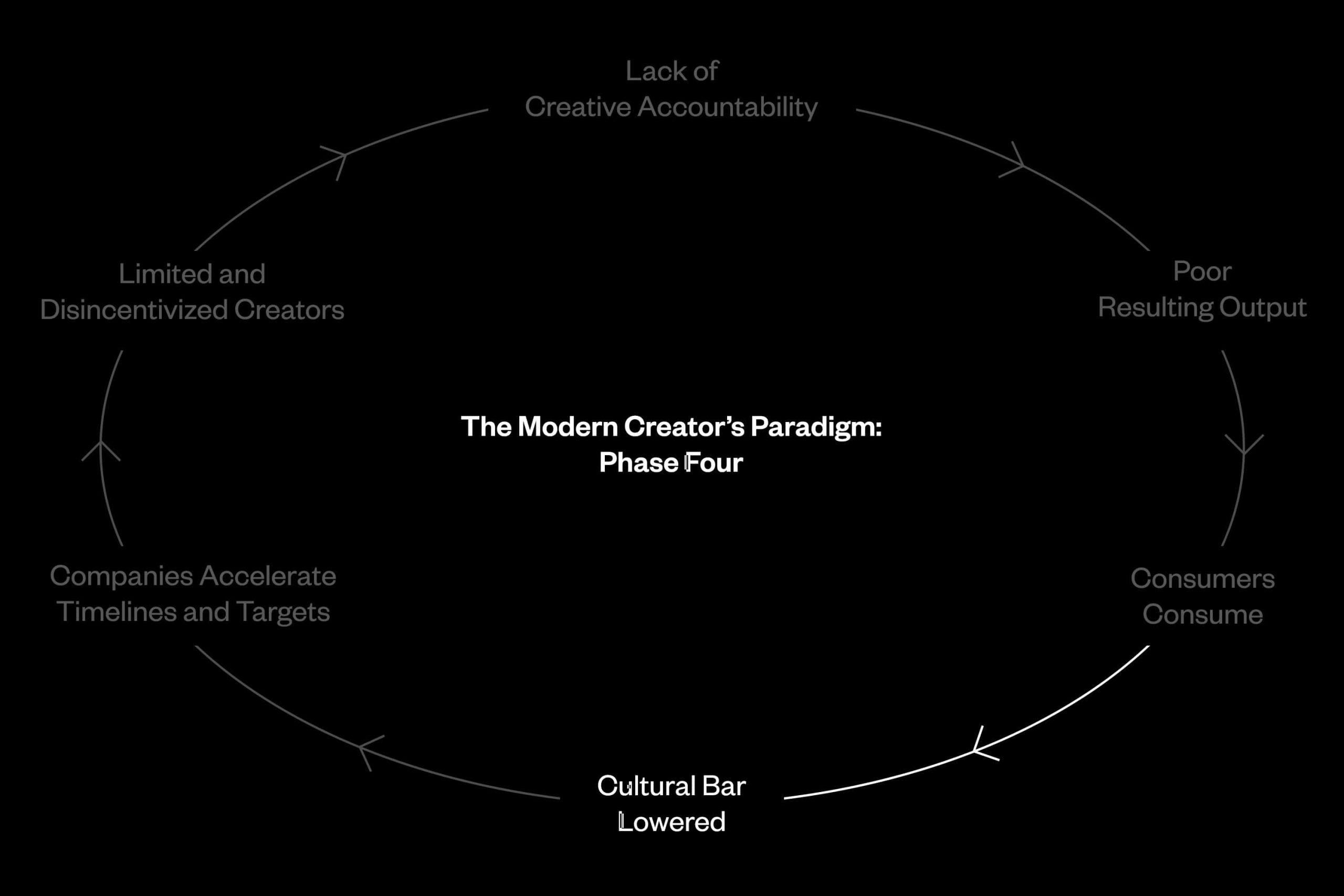

Cultural Bar Lowered

The continued consumption of poor output keeps the momentum of creation and production going. Society’s perception of quality is dulled and fewer opportunities are given to innovative, avant-garde ideas and objects. In media, the best content tends to be behind paywalls. In fashion, direct-to-consumer brands may deliver greater value.

In the general arena, anything of greater quality faces the challenge of standing out amongst all of the poor output continually consumed today. The abundance of attention-sucking output in the form of ads, click-bait, and, the worst of them all, salacious fake news junks up the landscape.

Toby Shorin, in his report on “The Diminishing Marginal Value of Aesthetics” put it this way, “…universal asynchronous accessibility and low distribution cost means that an aesthetic can never die. Somewhere right now, someone is discovering vaporwave for the first time, and can contribute to its longevity by participating in a lively subreddit…The main event, however, is a dampening on the overall effectiveness of aesthetic strategies. The combination of ubiquitous exposure and the obliteration of predictable context desensitizes consumers to aesthetic novelty. Just as aesthetics can no longer truly die, it is now difficult to create an aesthetic that will be experienced as truly new.”

“The combination of ubiquitous exposure and the obliteration of predictable context desensitizes consumers to aesthetic novelty. Just as aesthetics can no longer truly die, it is now difficult to create an aesthetic that will be experienced as truly new.”

—Toby Shorin, “The Diminishing Marginal Value of Aesthetics”

Shorin uses his longform thinking platform Subpixel Space to critically consider culture and media. Instagram account @diet_prada does the same by actively highlighting brands and designers who are copying the work of others.

The Fashion Law by Julie Zerbo also holds companies accountable by providing a perspective on fashion rooted in legal expertise. While these are good examples of enforcing creative accountability and preventing the cultural bar from being lowered further, their very existence shows the prevalence of thoughtless, regurgitated designs and concepts.

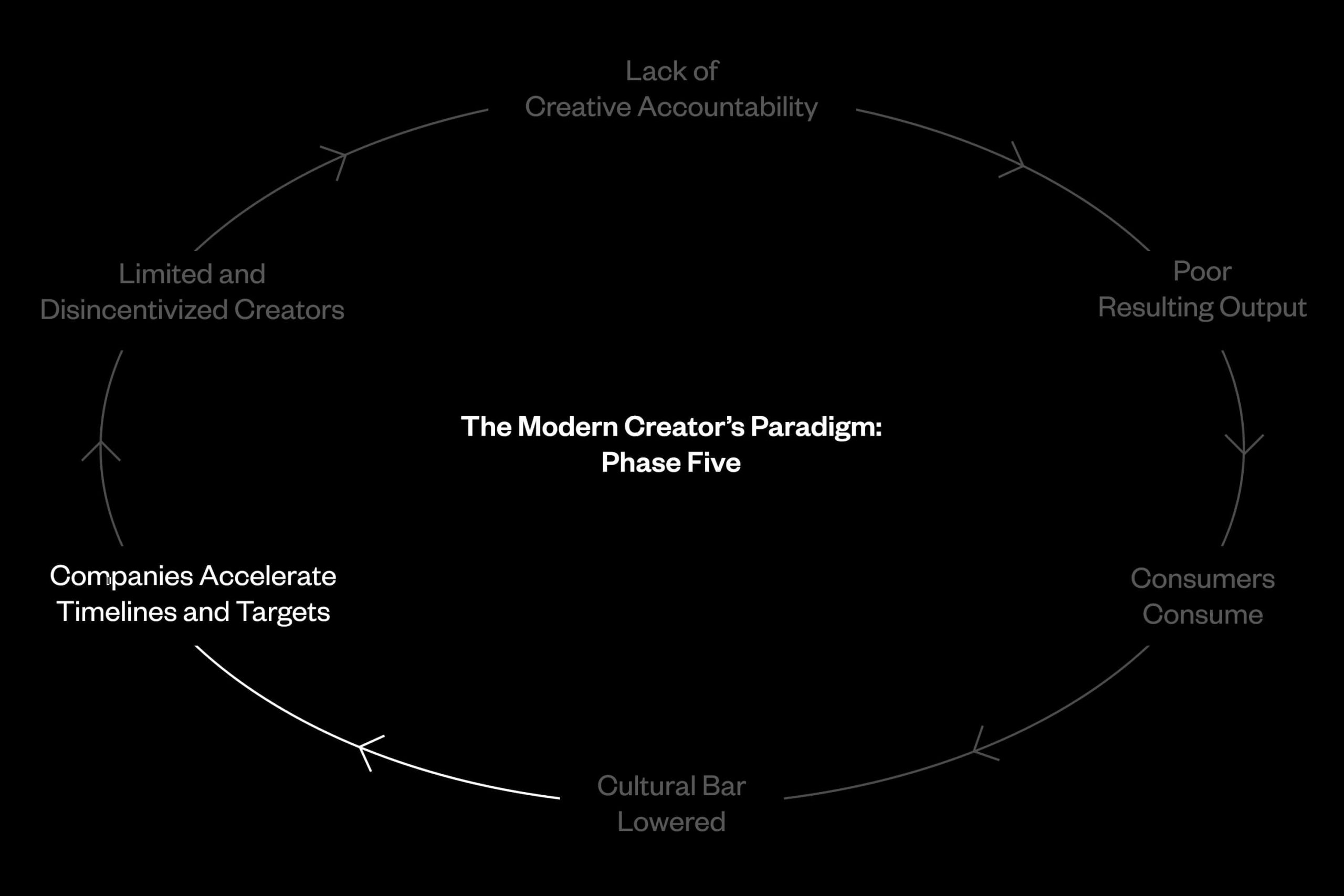

Companies Accelerate Timelines and Targets

Companies and brands optimize their systems for product creation and distribution. They are geared towards mass quantity and variation in order to remain the focus of attention over long periods of time.

Images pulled from Pinterest are posted to social media purportedly to inspire. Five or six collections a year are debuted with in-between lines like Cruise/Resort and Pre-Fall mixed in. Fast fashion’s soulless and optimized supply chain allows products to go from 2D image to tagged product on store shelves in three to four weeks.

In 2011, former Lanvin designer Alber Elbaz told British Vogue: “You start to understand why some designers do strange things, why some designers talk to themselves, you have to find a way of dealing with it all.”

“Today, designers are expected to produce work that is bigger, better, faster and – these days – cheaper. A singer can quit once he or she has made ten great songs, a director can finish once he or she has made five amazing films, a writer just needs to write three great books. Now let’s look at designers – they produce six to eight shows a year, most designers have a 20-year-long career, so I need to create about 250 collections in that time. Not even Danielle Steel could write 250 books.”

—Alber Elbaz

Limited and Disincentivized Creators

As creators attempting to make meaningful work while financially sustaining themselves, all of the other parts of this loop are discouraging.

There is now less space for creators interested in refined concepts, critical thinking, and creative accountability in the form of valid critiquing and more intelligent incentive structures. In the end, the best work of individual creators is neither properly seen or understood. Creatives feel pressured to turn out high-quality work in unsustainable timelines and environments.

Plagiarism is a particularly troubling problem that’s arisen. Susan Scafidi, founder and director of the Fashion Law Institute at Fordham Law School, stated in an article on the Business of Fashion that, “often customers don’t even know that they’re buying copies, because they have never seen the emerging designers whose work has been stolen.”

The landscape does not reward forward thinkers and so the forward thinkers burn out, switch vocations, or resign themselves to producing work mechanically.

Ultimately, plagiarism plagues the overall ecosystem because the lack of recognition for original creators coupled with the blatant disregard for their work and lack of strong legal systems to enforce them (fashion is notoriously loose in terms of how it recognizes ideas and copyright) means the whole system loses out in the end. If ideas were celebrated in a more transparent way, this would force top creators to always up the ante, benefiting everyone in the process.

Our time and dollars are finite. Brands and companies of varying agendas are trying to claim all of it. Innovative and honest content often lacks the marketing budget to win over our attention even though its truth and authenticity may bring significantly more value and insight.

The Hidden Cost of Community

“Community” is becoming the cliché of our times. It is the word around which businesses conceive their repositioning—create the community and then sell it your output. Ironically, in the past, businesses typically did the opposite: build a product, then build a community around the product.

For strong products and platforms, communities would build themselves. This was the case for the Jordan 1 and as well as for Instagram. The masters were Apple, because their original premise was to build tools to empower a community. Contemporary brands want to make the same magic happen but still rely on the wrong systems to supercharge the process. Money is not a good incentive for building durable, self-sustaining communities.

Our sense of “community” is also diluted since the word is used to describe any group of people that consumes, shares, and identifies with a brand, person, or entity as opposed to a group of people that gained membership to something through active participation.

Think wearing a Thrasher tee versus being able to ollie up a curb. Material participation isn’t an insignificant part of a community, but it’s the final phase of a lengthy engaged process rather than being the be all, end all.

Bypassing the process of making connections with other people to form a network of relationships by entering at the product level commodifies a community and makes it foundation-less.

Writer Casey Taylor put it best in an article on Deadspin where he broke down the current state of sneaker culture (a culture focused around a tangible product but wasn’t meant to be defined by it).

“The sneaker and streetwear culture has always been one of exclusivity, and markets of exclusivity have always favored those with means. But in this community, the means were traditionally unconventional. You made friends with the employees at the boutique, or had a friend of a friend who knows the owner of a shop or works at Nike. Now that the means conventionalized by tech ‘disruption,’ the market is playing out the way every other market ever has, with wealth begetting wealth and those without being left behind. A culture lives and dies with the passion it inspires in its participants, and the passion is draining from the most devoted.”

So what can we do?

Putting the brakes on this downward spiraling loop starts with reviving creative accountability. When we question and demand more qualitatively from all the “stuff,” we heighten the quality of output and we rebuild the relationship between creators and consumers with purpose.

Ultimately, creative accountability does this:

● Challenges creators to have a vision

● Creates a respectful relationship between creators and their audiences

● Incentivizes creators to make bolder work

● Lifts the cultural bar

● Inspires consumers to think critically and analyze output thoughtfully

● Nurtures relationships built on meaning and purpose

● Encourages positive participation rather than mindless consumption

Breaking free of the paradigm is difficult, mentally challenging, uncertain, and probably financially unrewarding in the short to medium run. Asking yourself, “why does this exist?” and “what is the purpose of this?” doesn’t necessarily lead to direct, illuminating answers.

Any solution needs vision, knowledge, commitment, and an understanding of our constantly shifting culture—not simple ingredients! Initiatives such as Booooooom’s Feedback Club, that welcome critique and analysis are examples that allow creators to better understand their work internally and externally. An open dialog, which will most likely need to occur outside of a social media setting, are methods to stress test our ideas.

The goal is not to put back in place traditional gatekeepers that hoard control and power by declaring what’s good and what’s bad dictatorially. The goal is for each of us to spend our attention, thought process, time, and money with care. We all are our culture’s gatekeepers. When we aim to fortify culture by using critical thought and analysis, we are rewarded with a landscape deserving of our efforts.

Critical thought and analysis, a dose of skepticism, and creative accountability lifts good ideas and refines them. Those actions stress test ideas for longevity, sustainability, and your attention. The ones that don’t pass the filter are laid to rest.