Eric Lau is a London based music producer focused on making music that connects people and has a positive impact on society. He looks intentionally for ways that his music and his skills can inspire and encourage others, whether it’s through mixing albums, producing original work, or teaching young people. His desire to shift society towards goodness as much as possible can be traced back to how he got started making music.

Shortly before entering university, Eric lost his closest friend at the time to suicide. With the loss came the realization that life is short and that it is of the utmost importance to pursue the things that might bring happiness. While grieving, Eric became more open to trying new things and meeting new people. Back then, he discovered that music was both healing and a way for him to express himself. Since getting set down this path over ten years ago, he has pursued it with determination and intent.

Eric Lau is the kind of person and artist who may not be a household name, but for the people who know him, they’re big fans. He has worked closely with DJ Jazzy Jeff, most recently working with Jazzy Jeff on his new album M3. He has also worked with De La Soul, James Poyser, Dego and performed with Robert Glasper, Erykah Badu, and ?uestlove among others. This is by no means an exhaustive list of people.

When Eric’s first album New Territories came out in 2008 it received critical acclaim and was widely covered by the media, throwing him into the light. In the ten years since that album, while Eric has continued to put out his own EPs, singles, and another studio album, he has studiously been avoiding attention out of the desire for people to evaluate him based solely on his music. He preferred as much anonymity as possible so that his ethnicity wouldn’t prejudice listeners one way or another.

Recently, Eric has decided that he wants to be more visible out of a recognition that a larger platform can help him positively impact more people. For people with cultural backgrounds like Eric, seeing him succeed in music production makes real the possibility of doing similar. It’s because of the value he sees in magnifying his voice and self-expression that led to the conversation we had with Eric while he was in Hong Kong.

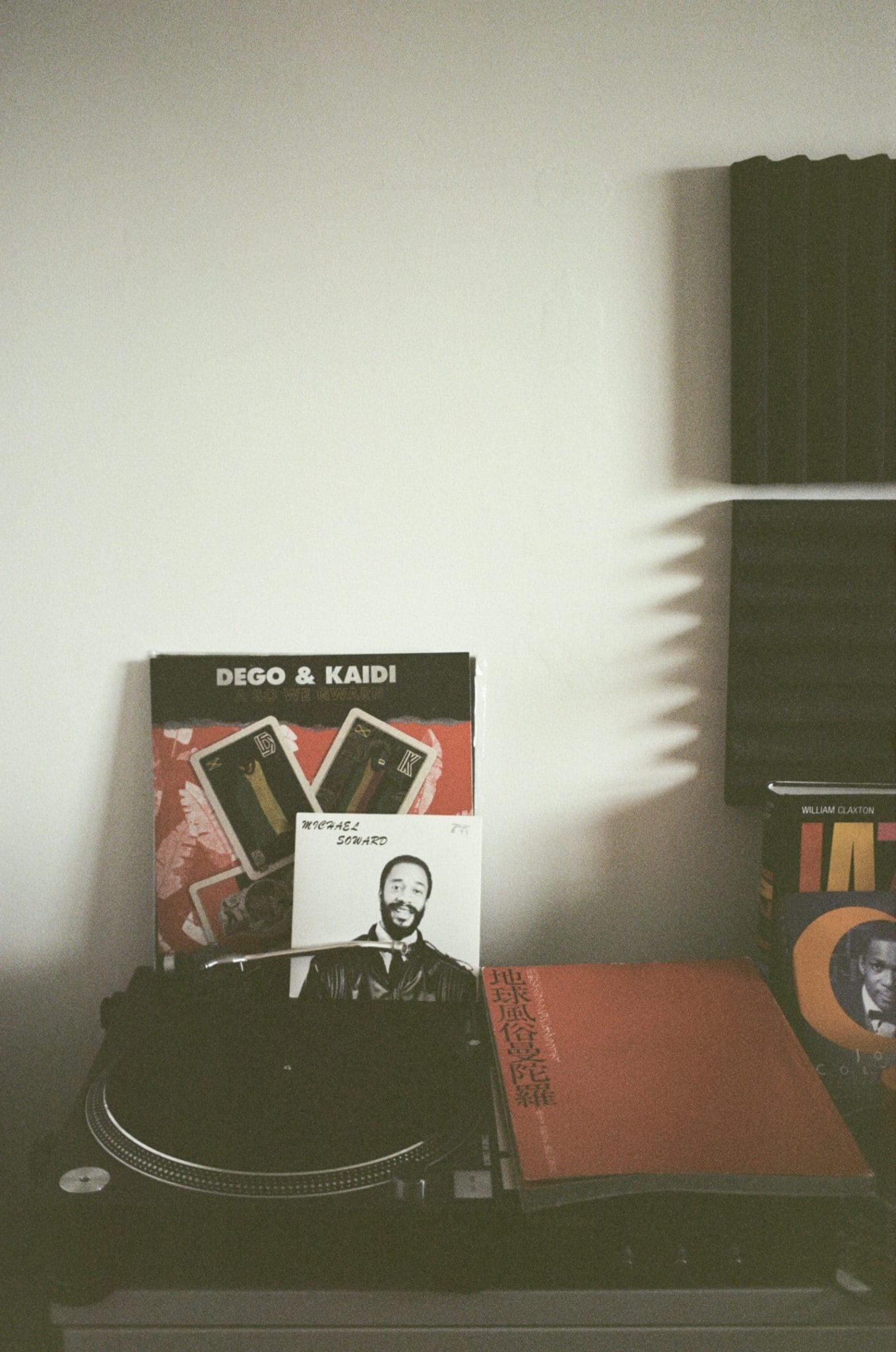

Eric in his home studio in London.

Eric Lau: Who am I? That’s a big question. I am a man in Chinese form. I was born in the UK and my parents are from Hong Kong. That kind of sums up who I am. I’m in the music profession. I am a music producer, mainly a mix engineer. I get booked to DJ, but I’d never call myself a DJ. And I’m an educator, so I do a lot of teaching and workshops with young people from all walks of life. That kind of sums up what I do. But, you know, I’m a brother, a son, a friend, a mentor, all of that as well. I just want people to have insight into what my life is like, I guess, in some way, and from a Chinese perspective as well, being in the West and all that.

Charis Poon: I wanted to start by asking how you got into it because you originally started by studying business.

Eric: Yes, that’s correct.

Charis: Ten plus years ago you had a different idea of how life would turn out then things panned out differently from your expectations.

Eric: Absolutely. After high school, we call it sixth form college in the UK so before university—I was 17, 18 at that time—unfortunately, I lost my closest friend at that time to suicide. And it really flipped my world upside down at that point. So when I went to start university in London—I was living in Cambridge before I moved to London—I was going through bereavement and at that time I was really open, open to try things, open to meet people, etcetera. London is obviously a great place for that. It’s a melting pot of different cultures and all walks of life. Music is strong there. I chose to do a business marketing degree because I didn’t know what to do in my life. It is a very safe thing to do, but, you know, gradually I met some really good friends and they were into music. One of my friends wanted to rap and make beats, but he didn’t have the patience to make beats. He bought some software and was like, “I can’t use this. Here you have it. Go try it.“ I tried using it and I have the kind of patience and the kind of programmer’s mind to learn software. I got into it and it was really good fun.

Charis: Can I ask about the aftermath of losing your friend and how you feel your mindset changed before and after that? It is interesting to me that you would say afterwards, while grieving, you felt open to many things and different people. It shows something about your personality, because other people would maybe close themselves off to everything or be more guarded as a result of something like that happening.

Eric: My childhood, being from Hong Kong, being Chinese, and then living in a little town called Ely above Cambridge—which is a really prestigious, white, academic epicenter of the UK—I was a minority by far in that regard. The school I went to, I went to a private school, a school called King’s School Ely and the kind of systems in place there are very old boy’s club mentality. I was like, “What the hell?” I didn’t understand this kind of culture. I went to a public school before that, so going to that was a big change. My parents were working in a fish and chip shop every day from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. at night, whereas everyone else at that school was quite affluent from being farmers or just old wealth. So that was a shock to the system. I never really fit in there. So when I came to London and after my friend’s passing, it was all hitting me at once. I didn’t want to live life like I did in Cambridge at school. I didn’t want that type of life. I never felt comfortable in it. That’s why I was so much more open to explore things that made me happy.I was like, “Oh, life is to live. Life is short.”In honor of my friend I want to make the most of it. He was a big inspiration for me to go this route. Unfortunately, my cousin and my auntie within a couple of years of that, as well, both committed suicide on top of that. So it made me just question everything. That’s why I was like, “You know what, I have to try different things.” Firstly, to kind of heal myself and to kind of have a platform to express myself in some way. And music came and I haven’t looked back.

Elphick Wo: Were you ever listening to music before during that time?

Eric: Absolutely. During the teenage years was more what your friends listened to. We didn’t have the internet then. So whatever your friends listened to, you listened to too. We were all into like, you know, Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and indie stuff, the 60s, the Beatles and all that kind of stuff, and Radiohead. That music’s all good and I really respect it, but I didn’t realize how depressing some of it was until my friend put me onto some funk and jazz and soul. I was like, “Ah, this is really uplifting, this is really empowering. Alright! Okay, cool.” We all knew about the big hip-hop stuff like Dr. Dre or Nas at the time, and I thought it was a band that did all that. And then I realized, “Oh my god, they actually took a bit of that old record and made a whole piece of music out of it.” I didn’t know that.

Charis: Did you just discover that on your own?

Eric: Just with friends as well. My sister was kind of getting into all the acid jazz music at that time, like Brand New Heavies and Jamiroquai, that’s kind of very London-centric. Then Erykah came. My sister bought Baduizm. I was like, “Hmm what’s this?” She bought it off a whim as well. She was like, “It looks really interesting,” so she bought it. I listened to it and was like, “Wow, this is crazy. This is really uplifting. It’s empowering. There are messages in there.”

Charis: This is before you started making anything yourself. So did you draw on that when you started learning the software your friend gave you?

Eric: A little bit. So that was some of the music education that I had: my sister and friends. My good friend, Julian, he’s got really good taste in music. He put me onto Donald Byrd and Roy Ayers and stuff like that, Curtis Mayfield, when we were 16, 15.

Elphick: That’s early.

Charis: That’s very good taste in music for 15, 16.

Eric: And then when I went to high school I played in a basketball team and there was a crew of us and they were really into hip-hop so they kind of schooled me on hip-hop quite a lot. And then when I went to college, first year I met my friend Hits and he was one of the best scratch DJs on the campus and he schooled me on the golden era of hip-hop. Which I knew the surface of, like Pharcyde or Gang Starr, but I didn’t know the record, the records, or who did what. And he kind of showed me all of that. He taught me how to chop a sample properly and how to juggle a record and all that kind of stuff. That mixed with, at the time, the Neptunes were killing it. The Neptunes were everywhere. So they were a big inspiration at that point as well as I was trying to make Neptunes sounding beats and Swiss Beatz and Just Blaze.

Elphick: I kind of want to hear those old projects from when you first started.

Eric: I’ve got them somewhere!

Dego and Kaidi Tatham are both influential figures in Eric’s life.

“I was just trying to learn. It was all new, all fresh, all exciting, an adolescent kind of approach to it. So I wasn’t even thinking that, I just wanted to do and share. That’s all I had.”

— Eric on his reaction to his early remixes quickly becoming popular online

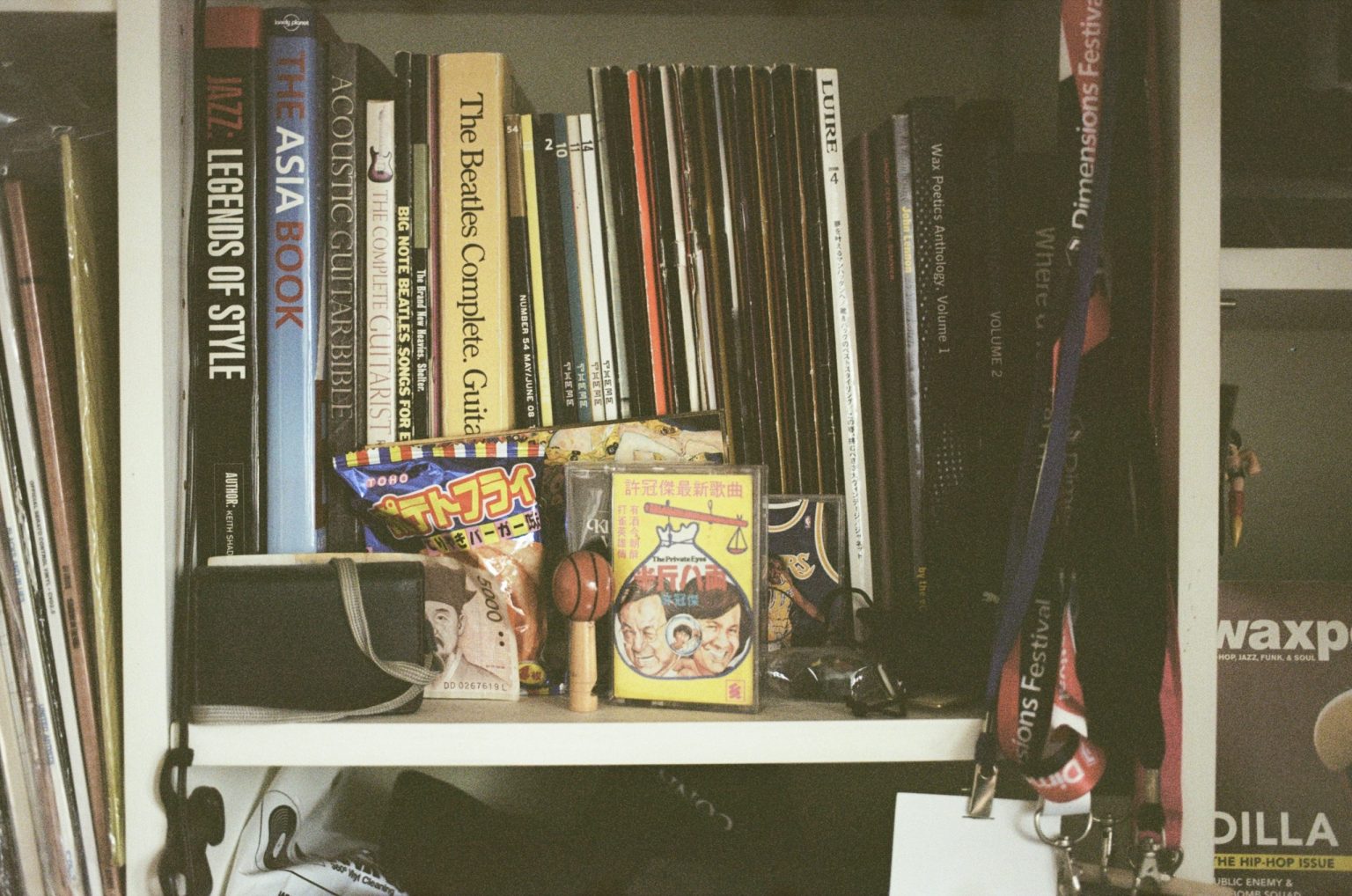

半斤八兩 The Private Eyes is a 1976 Hong Kong comedic film and an example of the kind of Chinese humor Eric thinks is underrated.

Charis: So when you started, I don’t make music so Elph might know this better, but when you start do you try to imitate something that you like?

Eric: Yeah. At the very beginning I didn’t know anything. I was using Hip Hop eJay. Then I moved on to Fruity Loops because you could put your own sounds in and, to be honest, I didn’t even know what a snare drum or a kick drum or high hat was. I didn’t know the names of those things. I had no concept of a drum kit. I had never seen one before in my life. So I hear the music and I see these things and I’m just trying to put it together. I made loads of weird music in the beginning and then after I learned, okay, this is how you use the software, then I kind of started trying to copy different pieces of music to see if I could do it and see what was going on. And then came into myself a little bit more.

Charis: Growing up did you ever learn an instrument?

Eric: No, not really.

Charis: Just curious because a lot of Chinese kids have some piano, some violin. So you’re actually starting from scratch.

Eric: Yeah. Nothing really. We had music class at school but it was all classical music and citation and I was not interested.

Elphick: When did J Dilla come into the picture?

Eric: After studying all the people I mentioned before, the Neptunes and all those guys and then going into DJ Premier and Pete Rock. Then came Dilla. I realized he’d done Pharcyde “Runnin’” which I’d heard years ago and A Tribe Called Quest stuff. This is the same guy! Okay now, I look more and more into him. I found that I could do Premier or Just Blaze. Well, not do them, I had the ability to imitate them. But Dilla, I was like, “What is he doing there? I don’t understand. What is he doing there?” Still to this day I’m learning from his music. That’s the genius of him.

Charis: In terms of timeline. When is this about? Still in college?

Eric: Still in college, third year.

Charis: At that time were you still thinking of it as, “This is a really fun hobby, it gives me joy.”

Eric: Yeah, hobby. Complete hobby. There’s no ambitions to do this as a career.

Charis: So what changed?

Eric: What changed was when I graduated I did an internship at BBE Records. J Dilla Welcome 2 Detroit, Pete Rock PeteStrumentals, loads of great reissues, DJ Spinna, Madlib. At that time they were doing a lot of great things for our UK based label because Pete Adarkwah, the owner, he gave people a license just to do whatever they wanted and that was quite rare at that time. So I was kind of doing an internship there just for the summer and one of my duties was to go to all the record stores and check on the stock. So I’d go round all the record stores and try to introduce myself to people. No one was very friendly to me at all, to be honest. I would kind of ask, “I make music. Can I give you my CD to listen to for some feedback?” No one really, apart from one person, one person. Sef from Deal Real Records and he’s like, “Yeah sure, play it! Play it now.” He let me play it on the system in the store. And he’s like, “Ah, this is really good. What do you want to do with it?” I said, “I don’t know. I’m just making music.” He’s like, “Well, you know, we help people.” You know, not like manage people in a way, but see what opportunities there are for you. So they gave me support in that. They introduced me to loads of people and I kept on getting good feedback and I was like, “Alright, okay, this could be a thing.” That was one of the turning points.

Elphick: Did you ever tell your parents at that time that you started to make more music, more involved in the process?

Eric: Yes.

Elphick: What did they think?

Eric: “You’re crazy.” They were very concerned. Very concerned, because I’d just done a business degree. I had no musical education. So for them they thought, “Oh is this just a phase?” Understandably. I would question the same thing if my child had never done music at all and then suddenly, graduated with a business degree and then wants to do music. I would question that. So I get it. So yeah, there was a little bit of a battle at that point, but we got through it and it’s brought us a lot closer now actually.

Charis: You kind of skipped over how or why you applied to the internship.

Eric: Oh, because I love the music.

Charis: But post graduation, or maybe there’s something different culturally, I feel like there would have been, for me at least there would have been, family or personal pressure to get a full time job that was future-proof.

Eric: Oh right, it was only for a summer though. It wasn’t that long. I was just a big fan of the music and my friend, who I went to university with, was already doing an internship there. So she was like, “Yeah, I can put in a good word for you,” and that’s how it happened. So I was like, I want to see how this all works and then, obviously, you’re right I had to get a job. So I got a job in a sneaker store and worked full time there to pay my way.

Charis: You must have had good feedback already leading up to that point from someone, from friends, from people around you, in order to have the courage to just approach strangers and say, “Hey, do you want to play this?”

Eric: So on the university campus I was making music with some people there, just people that I met. There was a music course there. I kind of dabbled a bit with those guys. This is the early days of sharing music, independent music, or bedroom kind of music online. There was a website, the original kind of SoundCloud, and it was called SoundClick.

Elphick: I have no idea. I’m too young. I only know MySpace. Was it before MySpace?

Eric: Before MySpace. And it was a forum and you could have a profile and there were different genres. So I remember doing this remix, a Nas remix and I put it up there. And I did this Mobb Deep remix and I put it up there. And they gradually just started climbing the charts in “The Most Played.” They got to number one and I was like, “Alright! Alright, okay.” People leaving comments and stuff.

Charis: Was it surprising to you?

Eric: Yes. Very surprising.

Charis: Did you have a feeling that you knew, like, “I’m actually talented. I know I’m good?”

Eric: I was just trying to learn. It was all new, all fresh, all exciting, an adolescent kind of approach to it. So I wasn’t even thinking that, I just wanted to do and share. That’s all I had.

“The hype machine can swallow up the best of us. I’ve seen it. I’ve seen myself get caught up in caring about what other people think when it doesn’t really matter. What matters is what the music does for society, really, and thankfully I’ve learned that.”

— Eric on staying grounded after New Territories was released and received critical acclaim

Elphick: Did you ever use an alias during that time?

Eric: I thought about that, but I think “Eric Lau” is an alias, really. Because my Chinese name I leave for my family only.

Elphick: What about after you gave your music to Sef? After that did they pave your way to make more music, plan it out for you?

Eric: They helped with introductions to people and getting my name around. I got my first paid job, production job, kind of being there. I did an internship there so I was working in the record store as well, so I’d meet people. And it was like the hub. Everyone passed through there. Kanye, Mos, Pharoahe, and, you know, whoever, John Legend. So I was meeting cool people and getting to know them, and they would be like, “Oh, you need to check out my boy Eric.” So you have opportunities like that. That kind of gave me a bit more confidence and it was all very exciting. It was pure hype all the time. So I got caught up in that whirlwind a bit.

Elphick: Did you ever get to show your music to the people you just mentioned?

Eric: Mos. Yasiin at that time. Ghostface. Ghostface was like, “Yo, I want some of those tracks.” It never came through. But, my first job came from this artist, this duo called Hill Street Soul. It’s a British soul act, a singer and a producer. They were relatively doing well at the time when they gave me my first paid job. They used three of my productions on their album and I was like, “Oh my god, I’ve got some money from making music.” I couldn’t believe it.

Elphick: Were you just providing the beats and having someone else to mix it down?

Eric: Yeah. So very early stages.

Charis: Is there someone from this stage who was a kind of business mentor to you? Because with creative work there’s kind of two sides right. There are people who teach you about making the art, like your craft, and then there are people who teach you about how to actually make money from what you’re doing.

Eric: Unfortunately, no. No, I didn’t have that at that point. I didn’t have any of the resources that we have now online either, like Bandcamp is incredible. Or just being able to distribute your own music to Spotify and iTunes so easily. The infrastructure wasn’t there then.

Charis: So how did you figure things out? Like every time something happened, you’d think about it on your own, like, “What do I do in this situation?”

Eric: I mean I had a few elders tell me things, but what they were telling me was going over my head.

Elphick: Did they ever pressure you to sign a record deal?

Eric: No. Generally, that was the way. So after a while my management signed a couple of other artists and they just didn’t have as much time for me. So I was like, “Well, I need to get things going.” So I went on my own and hustled a bit more, just worked on my craft a bit more and recorded some demos. The story is my friend, Andrew Meza, hes from L.A., and he was doing this kind of college radio station which turned into a kind of website, kind of music collective called BTS Radio—Beneath the Surface Radio. And he asked me for a guest mix and this is MySpace days. He was one of the first people to play music from Flying Lotus and Hudson Mohawke and Samiyam, all that stuff, kind of Soulection before Soulection. I did the mix and I saw that he worked for Ubiquity Records. I was a big fan of theirs at that time. Michael McFadin owns it now. I saw that he worked for them. I was like, “Oh, I’m a big fan. Could I give you my demos to pass on?” And he was like, “I didn’t ask you because I thought you were already signed.” I’m like, “No.” So he passed on my demos to Andrew Jervis who was the main A&R at the time. And he really enjoyed the demos. A few weeks later they gave me a deal. That was it. And that was all before I turned 25 and I set a deadline for myself for 25 to actually get a deal. So that was a big turning point for me.

Elphick: During that demo phase did you already have artists singing on your tracks?

Eric: Rahel and Tawiah, Tosin and Sarina. We cut like five, six songs and that was passed on.

Charis: That became New Territories.

Eric: Yeah, and that became that.

Charis: So you were ready. You had a thing and you were just waiting for someone or looking for someone to take it up.

Eric: Yeah, kind of, yeah. Well, you know, I was just doing it regardless. I wasn’t thinking about industry or anything. I was just making music and this opportunity came. You know, in hindsight looking back I was nowhere near technically ready, but I think what Andrew Jervis and those guys liked was the vibe and the sentiment of the music which is the most important thing for me. It’s a dual meaning. New Territories in terms of Hong Kong where I’m from and new territories for the group of people doing this type of music.

Charis: Ubiquity still has press releases from New Territories online that you can find. There was a music magazine that reviewed your album and compared you to J Dilla. Did you read the reviews?

Eric: Yeah, I think at that stage, that’s way… I mean no one can be compared to Dilla, really, to be honest.

Charis: I’m just wondering if that had an effect on you, releasing an album, getting all this critical acclaim, suddenly people are talking about you when they might not have been before.

Eric: Yeah, it definitely contributes to your ego 100 percent. Thank god I had met some really good elders to keep me in check,because that hype machine can swallow up the best of us, to be honest. I’ve seen it. I’ve seen myself get caught up in caring about what other people think when it doesn’t really matter. What matters is what the music does for society, really, and thankfully I’ve learned that.It’s nice to get praise and it gives you a bit of confidence, but that’s about it, you can’t really take more than that.

Charis: But is this you in 2018 looking back and saying that?

Eric: No, because like, with J Dilla especially, I don’t think anyone has touched on that level, because he’s the innovator of modern production, so to speak. I think the epitome of modern music production is J Dilla. My aim was actually just to make a record that was like Slum Village, but with singers. That was my aim. So for someone to kind of make that comparison it makes sense in that way. Execution wise I was nowhere close there. I was just like a baby. I didn’t know what was going on.

Charis: It’s interesting because you said that earlier as well. You said that technically you were nowhere near ready for producing that. It’s interesting to hear you be able to see that growth so clearly. Is that how you felt in the moment as well?

Eric: Yeah, because I knew what I wanted it to sound like in my head, but execution wise it wasn’t coming through like I saw it and I just did the best I could at that time and I met my deadline. I’m the type of personality, if there’s a deadline I meet it.

Charis: Even if it’s self-imposed?

Eric: They put a deadline there. I didn’t want to let them down, I wanted to be professional. And that’s how you grow, you create, you trap it, you share it, you learn from it, and then the next one you refine. You get better and better.

When they were teenagers, Eric’s good friend Julian introduced him to Curtis Mayfield.

“Again I go back to the sentiment and the vibe of the music is key. Because if that resonates with people it doesn’t matter about the sound quality of it or classical technique of something. If you feel it, you feel it.”

— Eric on what he thinks draws people to his music

Charis: The only reason I would ask this next question is because you’ve already suggested that at that point you might not have been technically fully ready, so looking back at the different points that kind of gave you a bump in your career, how much of it do you think is a bit of timing, a bit of luck, a bit of someone else lending a hand when you weren’t even deserving of it.

Eric: I think it’s a combination of all of that. Again I go back to the sentiment and the vibe of the music being key. Because if that resonates with people it doesn’t matter about the sound quality of it or classical technique of something. If you feel it, you feel it. You know there’s some Dilla stuff which is likea crusty cassette, you know, really bad quality, but the vibe is so good you just want to listen to it over and over again. That’s the beauty of that. The essence of a piece of music, you know, can transcend the medium so to speak.

Charis: You said you think the most important thing is that music shapes society?

Eric: How the music can have a positive impact on society.

Charis: Do you see your music doing that?

Eric: I would like to say that it has affected some people in a positive way and that’s my aim—to impact people in that way.

Charis: Is there some example you can think of? Maybe people that you’ve interacted with.

Eric: I’ve had people tell me that they want to play one of my songs at their funeral. I’ve had people get married to my music. I’ve had people tell me they’ve conceived their first child to my music.

Charis: That’s a strange thing to tell someone.

Eric: Yeah, right. Uh huh.

Elphick: That must be an interesting feeling.

Eric: It’s crazy. It’s overwhelming. As the journey goes on you realize that you are not your music. You are not your art. That’s how I see it. It comes through us. You collaborate with people and once it’s shared it’s everyone’s. So it’s not really mine. It comes from somewhere else and it goes somewhere else.

Elphick: You worked with the singers in New Territories. Are there any significant events that happened between those small projects up until One of Many? In your music life or just what inspired you that led up to One of Many?

Eric: Just growth, maturity, spiritual growth. You know, Quadrivium was a… no actually, before that, just to give you a timeline. When you asked about the hype thing, you know, interviews and quotes, being compared to so-and-so, one key thing that kept me humble, well actually two key things. Firstly, my mother kept me humble. She doesn’t care if I’m working with so-and-so or being compared to so-and-so, it doesn’t matter. It’s like, “Are you alright, firstly?” Secondly, I was doing a lot of teaching. Teaching young people, teaching kids from all different backgrounds. So from young offenders to autistic young people to young mothers’ groups. Normal kids in after school programs, anything you can think of, and they don’t care who you are. Can you gain their respect in three hours and teach them how to make a piece of music? You learn a lot about yourself and how to communicate with other people and build a rapport. And that humbled me for the music industry, completely. So that’s part of the journey and that’s a very significant thing. And secondly, meeting elders in the music game. I met Dego. If you don’t know about Dego, one of the most pioneering producers in modern times, was the main part of 4hero, and the West London sound and now, 2000BLACK. I met him when Dilla passed away. We both played at the tribute, the first one in London. I gave him a CD, like I do, because I am a fan of his. Weeks later I got a text from him saying, “Who the fuck is Eric Lau?” Typical Dego response. And then after that we got to know each other a bit more and he’s been in the game over twenty-five years, so he’s taught me how to carry myself. His cavalier approach has taught me not to care about what anyone thinks and just how to conduct yourself as a minority in the West as well. You know, how to take pride in your culture and how to stand up strong and tall. So he was a big factor within my growth. Also his good friend Mr. Mensah, who to me is one of the greatest people on this planet. Sometimes we think, “Is he real?” Because he’s so loving and generous, always consistently righteous in everything that he does. He never says a negative word about anything. He’s like the Internet. You can ask him anything. He knows it. I don’t know how.

Elphick: What does Mr. Mensah do?

Eric: I don’t know. I’ve known him for 10 years and I don’t know what he does. He’s a musician, but I don’t know what he does. He’s one of the great musicians as well. He’s very low key. He guided me on the spiritual path of who I am, why I’m here, how to conduct yourself, how to handle certain environments, and he’s just helped me on so many levels, musically, as a mentor. Everything. So he’s a key critical person in my life. Owe so much to him. And Kaidi. Kaidi Tatham, he’s like my big little brother. He’s a genius. I don’t say that lightly. There’s not many people I call geniuses musically and he is. To me, he is music on tap. He can fit into any situation and make it better. And I’ve just learned so much musically from him. He always challenges me, always teaches me something new, and it’s such a pleasure to work with him every time.

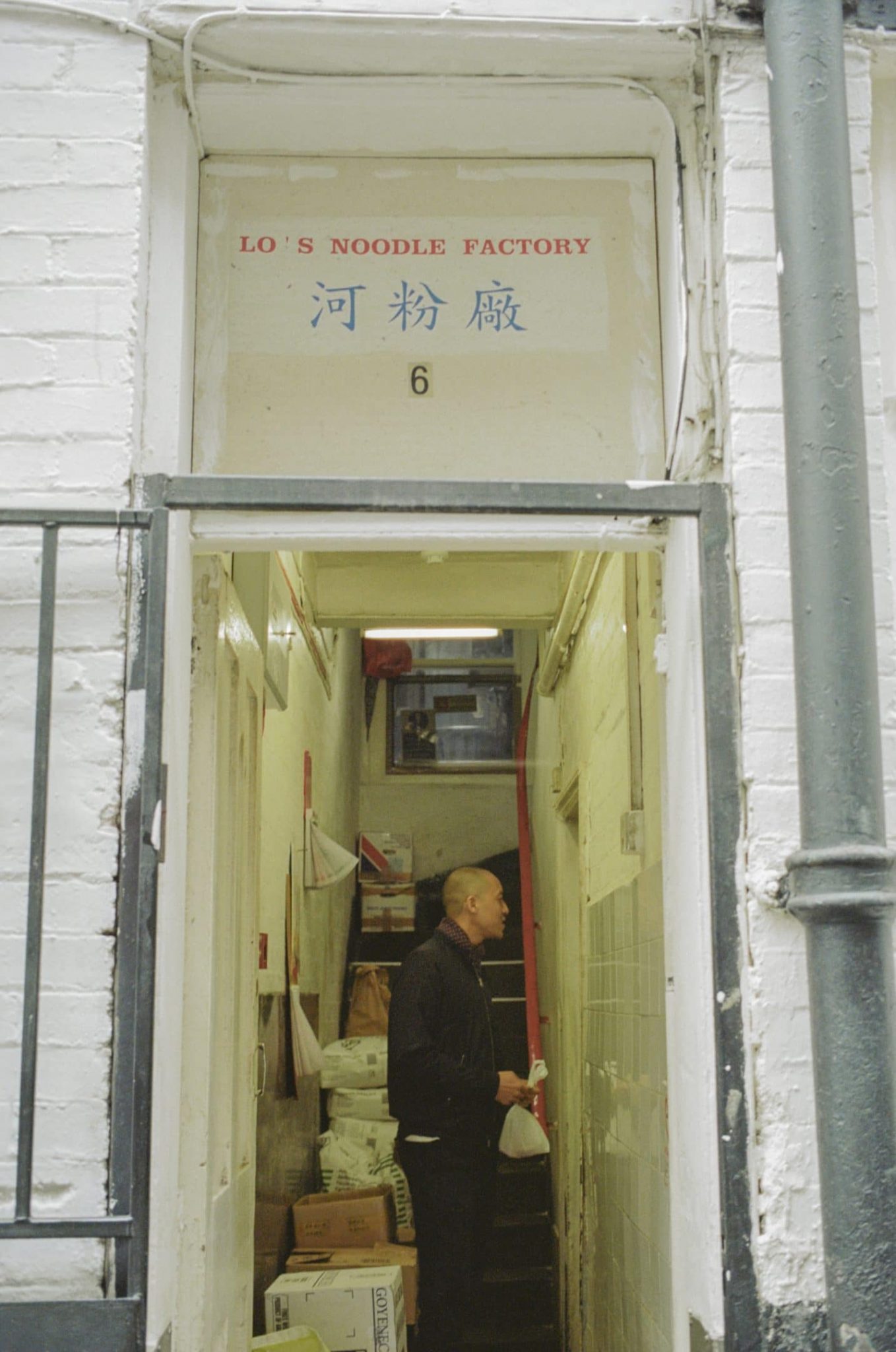

Eric in London’s Chinatown picking up some afternoon tea.

Elphick: Working with this type of artists, often they are musically very fluent, they’re coming from a very solid foundation of music as a language. Is there any way you felt like you need to keep up with that or is there anything that you need to do to match with that level and how do you kind of close that gap?

Eric: It’s learning how to use your strengths and weaknesses, really. So Dego summed it for me as a producer. If you know someone that’s better than you that can do that, then ask them to do it for you. Why do you have to play everything? You don’t have to. If you can direct and get whatever it is you can out of that person for the good of the music, then if you let your ego go then you can achieve great things. I never felt uncomfortable with those guys. I was in awe of them, seeing them play, but once they invited me into their sessions, you know, they would do something crazy, playing crazy progressions and timings and they’d be like, “Yo, Eric’s here, it’s your turn.” And it wasn’t like a pressure thing, it was like, do you whatever you can do.

Charis: This is coincidental, but I was reading a book today that had almost the exact quote. It’s a writer writing a book and he gets the advice, if you want to learn something find the person who does that thing the best and ask them to teach you. So it’s a little bit different.

Eric: Yeah, exactly that! They are the best in Europe 100 percent and some of the best in the world. So I couldn’t be in a better environment, to be honest. So that was a big part. You know, they would challenge me to do something in a different time signature. I’ve never done that before. Or play more keyboard. I’m not a keys player, but I’ll try some stuff and they’ll be like, “Yo, yeah, just piece it together slowly. It’s cool, just do your thing.” And then the tracks that we did, Dego chose to use them. I was like, “Wow!” He put that faith in me, he rarely does that for people, welcomes people in like that, so I felt very honored to be there, for sure.

Charis: You talked a little bit about spirituality and ways to conduct yourself. Is there some kind of guiding principle that you have when approaching relationships and music projects, something that lets you know this is the right path to be on or this is not the thing for me right now?

Eric: That’s a good question. One of the things Mr. Mensah taught me—I thought my sensitivity growing up was a weakness, was soft—he taught me that that’s my greatest gift, trust that. So when you apply that to music or in terms of decision making in music or anything creative or just energies of people, if you feel like it’s not quite right, then it’s not quite right. Trust that, trust that 100 percent. And I really do now. And it has only led me to goodness. So that was one of the great lessons I learned. I’m hypersensitive to everything, but once you develop and train yourself you know how to operate. When you can apply that to a musical environment or with relationships, it really helps. It really helps.

Elphick: Let’s go back to the timeline a little bit. This is great, these are great detours. So what was the reception of the second album? Let’s talk about your journey, the lead up, what changes were there in the second album.

Eric: I’m trying to remember.

Elphick: What year was that?

Eric: That’s five years ago. 2013. Five years already. The sentiment of One of Many, after kind of just doing a lot more research and becoming a bit more aware and meeting more musicians on this journey and artists in general—I’m just one of many people trying, as I said, to lift the vibrations of this planet in some way. Through art or through our interactions with others in general. I’m just one of many people and many of us, living things in the universe, we make one. So that’s the concept of the record. I wrote a little kind of mission statement of that and then I sent it to everyone involved so they kind of got that and then we created. And again I had a deadline. It was a tight one. We had many challenges, but we we managed to reach it. And the feedback was great. It was released on Kilawatt which is just one person, Simon Daley. He believed in me and I have a lot of gratitude towards his support, because I didn’t have any other outlet and he supported me, he funded the project, believed in me. It’s just one person, you know, it’s not a big label. We put it out there and the kind of press that we got was on par with, you know, people like Robert Glasper, when he dropped Black Radio. So all the blogs, all the websites, because we released at similar times, it was all us everywhere. So that’s with our money we put into it and that’s Blue Note. This is just one person. So at the time I was very proud.

Elphick: Did you time it? Did you know Robert Glasper was doing that?

Eric: No, no. So that shows me, if you put good quality out there and you get the right people to understand that, they’ll support you and that’s what happened.

Elphick: I’ve always been looking up to your path. Just checking the boxes, I felt like seeing how you became was very aligned with my calling. So it is a blessing to know that there is a Hong Kong Chinese producer who can make it in that world, can inspire the next generation of people that’s trying to do music.

Eric: Yes. That’s the aim. I’m not saying that doing music is for everyone or doing art or anything. It’s not a case of that. It’s more to see a Chinese face in a different context opens up the possibility for others to do something that they might want to do, that they think is not stereotypical and that’s very important. The older I have gotten the more I realize that’s really important and for you to kind of step forward in that with a bit more confidence, that’s exactly why I’m trying to be more visible and to be able to use these platforms like this to truly express myself. Because there aren’t that many Chinese Hong Kong people, you know, doing what we do.

Charis: Previously do you think you were trying to be less visible?

Eric: Absolutely. I was trying to not be visible at all. I didn’t even want people to know what I look like, to be honest.

Charis: And why is that?

Eric: It was an ego thing. I wanted people to take me on my music. Solely. Which is still the case in some regards, because if you’re not feeling my music that’s fine. I don’t want you to, if you’re Chinese and you see me that I’m Chinese and then you’re like, “Oh yeah, he’s really good!” Nah, if you’re not feeling it then you’re not feeling it, or if you’re feeling it then you’re feeling it. It shouldn’t matter what I look like. Or the reverse way, “Oh, he’s Chinese I’m not going to listen to this.” I don’t want that.

Charis: You don’t want people to conflate the kind of music you create and who you are as a person.

Eric: But now, I understand how important it is to be visible. As I said, because there are very few people, Chinese people, in this realm, and I realize I have an opportunity to speak and use this platform. And when I hear stories like from yourself and others, I would like to do that more and more.

Elphick: I feel like in recent years there’s definitely a big movement in Asian artists being highlighted. I don’t know if you know anything about 88 Rising and all those platforms that highlight Asian artists; what do you think of those?

Eric: Controversial. I think theres a fine line when it comes to hip-hop culture and black culture where you’re inspired by what they do, you’re inspired by the art and you embrace it and you can express yourself within the art in your way and find your voice in that. I am a Chinese man. I’m not trying to be anything else. And a lot of modern international hip-hop music sometimes, whether it’s from China or wherever in the world, I feel the way they present themselves, what they talk about, everything, I don’t believe it sometimes. I’m like, “You don’t talk to your mother like that. Are you really going to sit around the dinner table and be like that?” So what is that culture? That’s like a warped perception of what black culture is and they’re trying to present it that way and then to kind of profit off it, I don’t know man, I’m not really sure about that. Just being real. Real talk,

Charis: The way you have presented your decision in terms of being more visible, my understanding is that you have consciously made this decision because of representation, because of wanting to inspire other young people who might look up to you and not because you’re looking for individual fame or the glorification of your name. This is my understanding. But 88 Rising, I don’t believe that they have this perception of wanting to become more visible in order to give young Chinese people something to look up to.

Elphick: It’s all for the hype. I feel like everything they do is formulaic from America, what’s paved the way and they know works. So they are specifically finding artists that can be molded and shaped into that image.

Eric: Yeah, and it’s a warped perception. It’s not like they’re getting the black American producers and writers and engineers to go to China and to produce Chinese artists; that would be a different story. It’s them kind of assimilating the culture, really, into what they perceive it as, and to kind of gain from that. I can’t make a full judgment on this, because I don’t really know that music so I’m happy there’s a platform like 88 Rising—I really like the name actually, it’s really cool. I like the name. I don’t know, but what I’ve seen very briefly hasn’t encouraged me to look more, I’m afraid. As a Chinese man I’m like, “Oh god,” rather than, “Oh what’s this? Oh this is cool!” I’m not saying that; I want to say that.

Charis: On the other hand I do sometimes feel torn, because I feel like there should be room for Chinese hip-hop musicians to be bad at music.

Eric: That’s fine.

Charis: I do think there should be room for good and bad Chinese artists and that we don’t have to have the people who are globally recognized be amazing, but yet that is, the other part of me feels that way.

Eric: Yeah, I feel you.

Charis: I want the most visible Asian artist to be the best because there aren’t that many of them and because everyone is looking at these certain people.

Eric: I feel you. That’s what I’m saying. When I hear of these things I’m happy that people are expressing themselves and making music and there’s communities and movements and people are really active. That’s great. That’s important. And that adolescence is fine sometimes, but if it’s the only representation then that’s to the detriment to both sides, to Chinese culture and to black American music culture, because that’s where it’s from, is detrimental to both of them if it’s only that so there needs to be more.

Charis: To ask you again about you personally, you told us earlier this week that you’re planning to spend more time in Asia.

Eric: Absolutely.

Charis: Do you want to talk a little bit about that decision?

Eric: I just feel like I’m at a stage of my life where quality of life means a lot to me. I live in the village in Sai Kung and it’s very peaceful. All of my family has been there for hundreds of years. I kind of feel way more connected there. There’s a lot of nature around, family around. The main thing is that. Secondly, it’s because I feel like I would like to take back what I have learned from the West and pass on knowledge here and to learn from here as well. So I want to have more exchanges. I’d like to do work in universities or more workshops in music schools and get to know the musicians and artists from China, especially Hong Kong, and the rest of Asia. You know, I like to contribute and help in some way possible, in whatever way there is.

Charis: Is there anything that you feel like isn’t possible here that is possible for you in the UK?

Eric: Like musicians and artists because of the history of music in London and America. It’s been going on for hundreds of years in this realm of music, black music, and that’s my field. So I’ve met communities that really understand and have open-mindedness about music in China. Incredible people. But, in terms of that, I’m looking for that here, so I don’t think I’ll ever feel like I left anything behind because the world is so small now. I’m used to flying everywhere to work with people so that’s not going to be a problem.

Elphick: Coming to Asia, do you already see any changes that you can do that incorporate Chinese elements into your music or is there some sort of direction that’s completely different than what you’re doing in the States or the UK?

Eric: I feel like the energy of my music, the emphasis, and the intention behind music hasn’t changed since I started. So that framework, that frame, you can put anything in that frame. So whether it’s Chinese or Brazilian or African or whatever, it can work. Yeah, it’s definitely possible. You know I have got so much to learn about Chinese culture and Chinese music culture. It’s something that I would like to explore and to hopefully frame and share in a different way.

“To see a Chinese face in a different context opens up the possibility for others to do something that they might want to do, that they think is not stereotypical, and that’s very important. The older I have gotten the more I realise that it’s important for you to step forward in that with a bit more confidence.”

— Eric on his decision to be more visible and expand his platform in order to hopefully inspire more people

Elphick: I want to ask a little bit more about the Jazzy Jeff retreat. What did you gain out of it? And what are the stories behind that album Chasing Goosebumps?

Eric: James Poyser, legendary producer, keyboard player who actually produced Erykah Badu’s Baduizm, which is one of the main albums that kind of, you know, changed things for me when I was really young. We had dialogue from New Territories, because Ubiquity sent my album to him and he gave me good feedback. I said, “Oh you inspired me, you and Dilla especially.” He played my music to Jazzy Jeff. Jazzy Jeff hits me up on Twitter immediately like, “Yo, love your music, man. I’m in London in three weeks, you know, let’s link.” And then we met up. He was with his wife, Lynette, and the kids, the twins, and we just talked about life, music, basketball, until 3, 4 a.m. and then he invited me to his, for these PLAYlist Sessions. So the PLAYlist Retreat is something that Jeff does every August, where he hand picks and invites around a hundred DJs, producers, artists. There’s like seminars, talks, and everyone kind of gets to know each other and share their experiences bad and good. He just wants to build more of a community so that we can bypass, you know, the old models of industry. And he’s doing that, he really is. The PLAYlist Sessions is another wing of that where he invites music makers and we come together and we just make music. So Chasing Goosebumps, he had the idea to do an album in seven days and to livestream it and release it on the seventh day. And it was one of those situations, as you said, you’re in a room full of the greatest musicians on the planet. How can you contribute? So I kind of fell into the engineer, traditional music producer role, where I wasn’t necessarily playing loads of keyboard or stuff. I maybe had the starting point or maybe I’ll keep the vibe going or just record everything properly and get the sound right. So I gradually found my role and it’s been one of the greatest musical experiences I’ve ever had and I’m learning from them all the time. That’s my kind of Jeff relationship and he’s took me in. Yeah, he’s just a very generous, wise, loving man, one of the greatest people I know. Much respect to Jeff, much love.

Elphick: It is very inspiring to see, like, “Oh, you don’t need a record label to do this.” And just having that many resources and people to create something very fresh. Would you guys do it again?

Eric: This is just the start. We’re doing many more things. Jeff has had a few little kind of conversations with us about trying to change the model of how it all works and I mean, I can’t reveal anything yet, but it’s coming. And it could potentially mean that we come together to make music more often and to have more flows of albums coming out, like back in the day where you had Motown or whoever. Have a core group of people continuously working, that’s the aim really. How do we do that where everyone is treated fairly and is going to have, how do I put it, in terms of the business, it’s sustainable and fair for everyone.

Charis: If we can bring it to the present, what can you talk about that you are working on right now?

Eric: So I’m just mixing Masego’s album, young artist from Virginia, really talented. So his album is coming out in the summer. I mixed another artist called Emmavie’s album just now. She’s an incredible vocalist, producer, arranger from London. I’m doing a second volume of Examples. Examples is an instrumental project, so volume two of that. Then after that I’m doing my full length album, my third full length album, and that’s coming out, maybe, next year. That’s what’s happening. And Jeff’s album just came out! So, you know, I recorded all of that and did the production on that with Jeff. So that just came out, M3, which is the third installment of the magnificent series. And Kaidi’s album, I helped mix Kaidi Tatham’s album that’s coming out in a couple of months. So there’s a lot.

Elphick: Amazing, we look forward to hearing all of them when they come out.

Charis: If we can forecast ahead, like not even in terms of projects that you know are currently existing, but looking to the next five to seven years what do you hope to accomplish.

Eric: Wow. I want to produce some babies. That’s what I want to do.

Charis: We’re going to end the tape right there.

Eric: I want a family, for real.

Elphick: You’ve been saying there for a minute.

Eric: I want to have a family, main thing. I mean I’m setting up my label, so my next album’s going to be on my own label. I want to mix more records for people. I want to do more stuff with the PLAYlists and make great albums with them. I don’t know, that’s it really. I kind of go with the flow, really, to be honest. But having my own label will allow me to release music more quickly. I want to be able to… I haven’t got enough music out there, to be honest.

Charis: Are you going to bring other people onto your label?

Eric: Yeah, definitely.

Charis: I’ve got a light-hearted question. What is something not music related, not career related that you think doesn’t get enough notice? It could be food; it could be a place in Hong Kong. Something totally underrated.

Eric: I think Chinese humor. I think it’s something that I have really missed in my community in London and in America. I don’t have many Chinese friends within those communities; I’m the only person. So when I come back and speak Cantonese and talk to people and hear the Cantonese humor, I haven’t had that feeling for a long time and it’s such a different type of humor and I think it’s very underrated. One of my earliest memories from Hong Kong films, cinema, is 半斤八兩 The Private Eyes. And I watched that a couple of years ago and it’s still amazing to this day. It’s hilarious. One of the funniest films I’ve ever watched, so I think Chinese humor is very underrated.

Charis: I know you are someone who’s been teaching for a long time and working with young people and excited about artists who are just finding themselves. Who is someone you are excited about?

Eric: I mean Masego. He’s super tight; he hasn’t even started yet. People don’t realize the depth of his talent in terms of musicality. He plays everything. People know him for playing sax, right, and singing but his keyboard playing. I was telling him today on the phone, there was a point where we’re at Jeff’s and he was just playing us things he’s been working on and there’s a piano piece he probably recorded with his iPhone. It sounded like a 1940s, 1950s jazz player and me and Kaidi were like, “Is that you?” and Kaidi was like, “No, no, that’s not you.” Masego was like, “Yes, that’s me.” Kaidi couldn’t believe him. So Masego, he’s even more talented than the music that he produces now. Other young artists—Amir, Jazzy Jeff’s son, is 18-years old and he’s already done, like, three projects and he already knows how to engineer his own vocals and he’s super intelligent, super talented. Gwen Bunn, she went to Berklee, she can play jazz level piano, but she’ll produce “Collard Greens” for ScHoolboy Q and then she’ll do something with Phonte and them, and then she’ll work with 9th, and then she’ll work with us. She’s just incredible in that. There’s so many. It’s really healthy right now, music, the young generation, I’ve got to say. There’s loads of great young musicians in London as well. There’s too many right now to name.

Charis: This has been great to hear. It’s good to hear you get excited about people.

Eric: Oh yes. So much. I’m just a fan of music.

Tracklist — Visit Eric’s Bandcamp for more music and information.

FW150

Can I Get a Witness

Open Up

Dreams

The Best Good

Old Beat 2

Old Beat 3

RAHW

Circles

Love Vamp

The Sun Beyond

Masamba

Re_Lax

Flute Time

4 De La

Good Evening

Many

Here feat. Rahel

Where To Go Now

One

Closer

Rise Up

Guide You

Not Alone

Divine

For You