The office of Takuma Inoue’s interior design firm is located on the fifth floor of a building in the Gion district of Kyoto facing the Kamo river. This building, y gion, has been Takuma’s ongoing project for the past two years and is the base from which he hopes to nurture art in Kyoto to be “locally grown, internationally known.” He looks to bring together the traditional and cutting edge in fresh ways that will draw global attention. Takuma and I talk while seated across from each other at the communal table that occupies 40% of his office. To our right is an uninterrupted view of the traditional machiya townhouses across the river. While the district where y gion is located has a long history, the room we’re sitting in and the entire five-story building is of an unmistakably contemporary design—Takuma began renovations on y gion, a former hostess club, two years ago.

In 2012, Takuma started his interior design firm Everedge at the age of twenty-seven. The owners of the y gion building approached Takuma a year after he opened for business asking whether he’d be interested in spearheading their renovation project, but they wound up not agreeing with his pitch. Takuma recalls, “After three years, they asked me again because the building was still empty and nobody was doing anything. So I came up with the concept of a multicultural platform.” Now, besides running Everedge, Takuma concentrates his time and energy on being y gion’s creative director.

While the location of y gion is right by the river in the heart of downtown Kyoto, this neighborhood has an unresolved history that has rendered it relatively quiet since the bubble burst in Japan in 1992. The street y gion is on seems especially deserted when compared to the nearby Hanami-Kōji Lane that every season is packed with tourists hoping for a glimpse of a geisha and taking selfies in their rented kimonos. During Japan’s economic boom, this part of Gion, sandwiched between two major roads, was filled with hostess clubs, bars, and discos. When the economic growth halted, people stopped spending money on night life, including the former hostess club called Snack that lay vacant for seven years before it was transformed into y gion.

The Gion district in Kyoto.

The y gion building in the Gion district.

The y gion noren curtain.

The walls, ceilings, and floors of y gion are mainly composed of concrete finished to a degree that looks intentionally polished, but still imperfect enough to still feel industrial. The lighting throughout is warm, transforming the otherwise grey rooms into appealing, comfortable spaces. Each space in y gion is flexible, as easily converted into a retail location, a bar or restaurant, or a gallery. Large balconies and floor to ceiling sliding glass doors open up the indoor spaces and incorporate Kyoto’s beauty into the building’s design. The rooftop bar, which hosts chu-hai bar Sour in the summer, is exactly the kind of place where a group of friends would want to hang out. To me, the exterior of y gion hints at contemporary art museums; the sheer unbroken concrete surfaces, undecorated windows, and the use of natural light remind me of the Benesse Art Site on Naoshima island. Visitors enter the building through an entrance that is two stories high and has a long light brown noren curtain hanging from the top. The contrasts in materials and color—concrete and wood, grey and brown—echoes the kind of intersectional events Takuma organizes.

While Everedge is thriving, Takuma was looking for ownership over his own projects. “I’m still an interior designer and I love doing what I love. But when you do interior design we give a lot of ideas and then when the project is finished, I hand over the project. Maybe in two, three years when they’re successful they’ll give us a new project, but to me I wanted to have my own ideas.”

He felt like he was putting a great deal of time into crafting thoughtful interiors for restaurants, hotels, and living spaces that would wind up under other people’s jurisdiction. He was in charge of the initial launch of a place and then detached from the actual use of a location over time—how people inhabit it, what events are hosted, and what kind of culture is nurtured.

“If you mix cultures like art and music people who are not interested in art become interested, because they came for the other thing and accidentally find something more interesting. If I don’t provide those spaces that express not one, but two or three creative realms, it doesn’t expand.”

Takuma browsing the artwork of Yukihiro Tada that was on display at y gion during the 遊体離脱 exhibition.

For Takuma, it was especially important to be a creative director of a building in his hometown, which he feels is still missing a meaningful art environment. “I think people are having difficulty expressing themselves. It’s kind of like they have a mentality of building an art life over a long period of time, which means they don’t know how to brand themselves. I wanted to start this creative directorship for the younger artists or the artists who have a problem expanding their work to the world.” Takuma has high expectations of himself as it pertains to his responsibilities. “I think there’s a difference between being a creative director and being a producer. In the past in Japan the producer was the one who ran the world. To me, producing is connecting this designer to this owner or this restaurant to the other restaurant, just connecting. There is no creativity in it. I think ‘creative director’ means to direct, you know, from the word itself. So when you connect two people or try to create “mixed culture” you need to have your own idea or your own concept to connect people.”

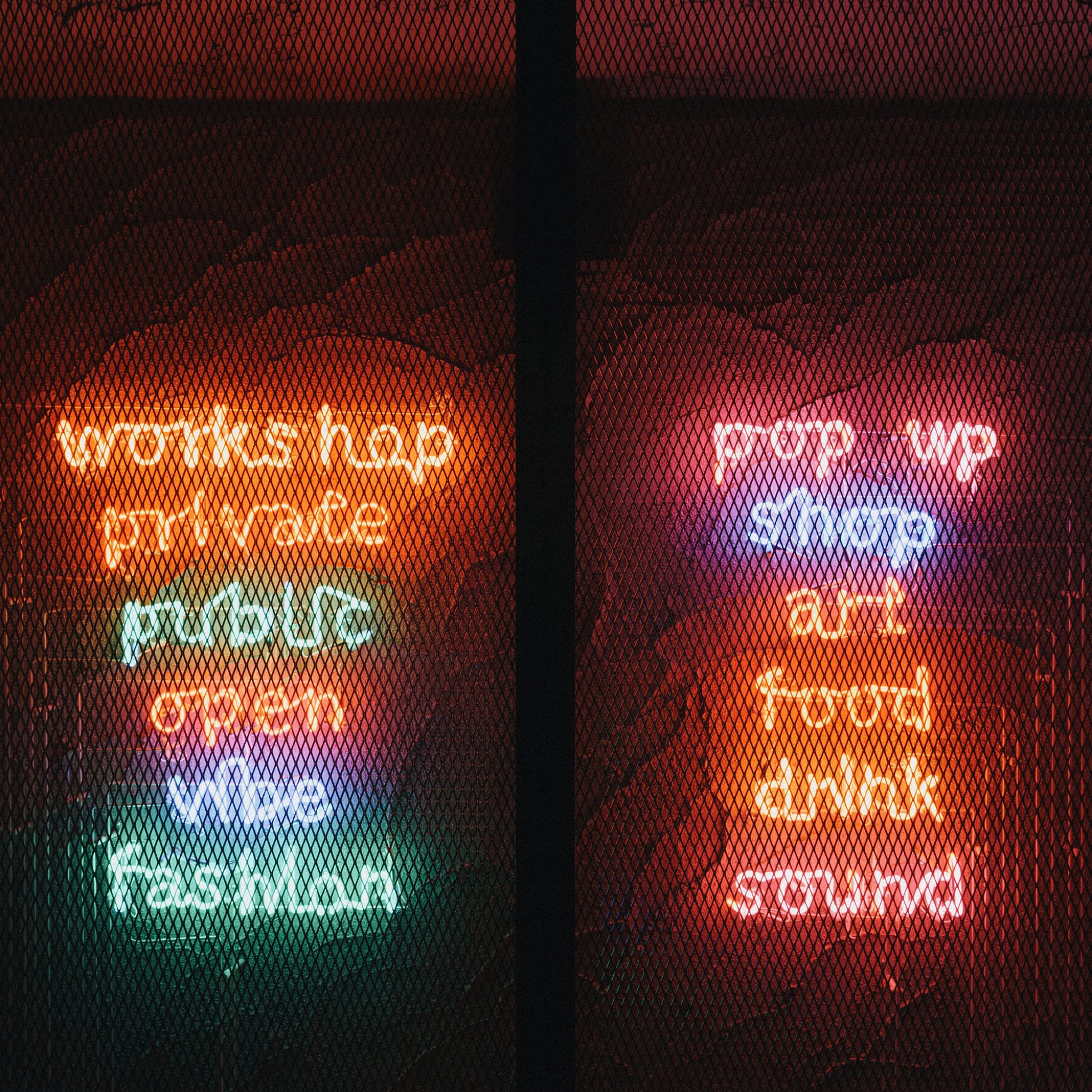

The term “mixed culture” requires a little more elaboration. Takuma goes on to say, “We create events that are “mixed culture.” We have food and art, art and music, art and sound. ‘Mixed culture’ is our concept. Let’s say someone is interested in food and comes for the food; maybe one out of ten people becomes more interested in the art and that for me is expansion of the culture.”

Part of y gion’s core mission is to connect disparate creative concepts in a way that appeals to all kinds of people while supporting artists. Takuma continues to explain how y gion is doing something different by describing the cultural climate in Kyoto. “The problem in second cities is if you want to do something in music you start from the underground, but the underground scene just stays underground. If a hundred people come, it’s always the same one hundred people. It doesn’t expand. And I think, ‘Why is that?’”

Onigiri prepared by Shokudou Ogawa at a pop-up event.

Seared tuna prepared by Shokudou Ogawa.

Head chef of the extremely difficult to book restaurant Shokudou Ogawa.

An event attendee taking a close look at the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto.

Beatmaker Phennel Koliander spinning tunes.

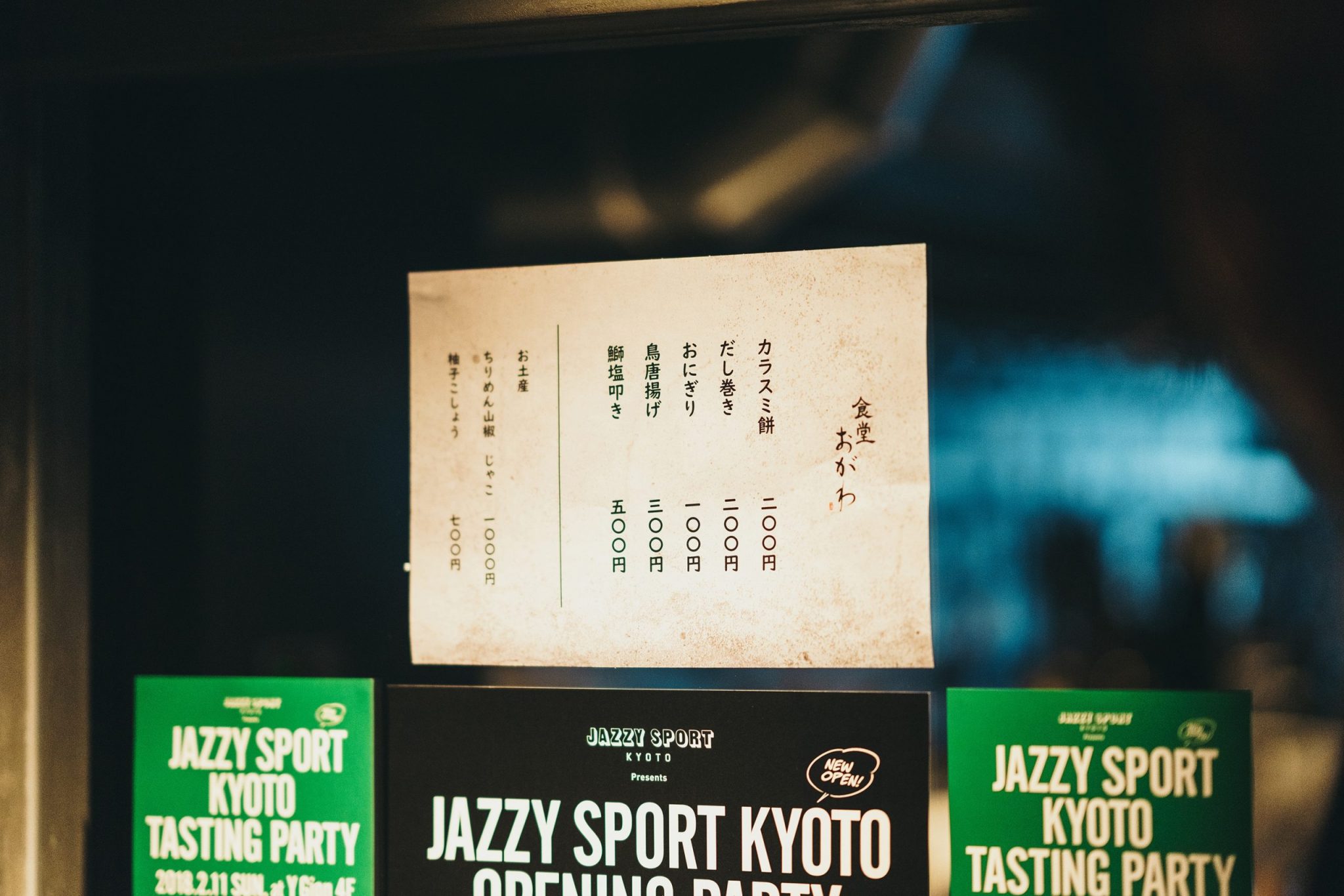

Menu for the Shokudou Ogawa event with flyers posted underneath advertising the opening party of Jazzy Sport Kyoto.

Takuma lived in New York from the age of sixteen to twenty-three. His time in the States changed the way he thinks. “I saw a lot of art coming from the street, like Andy Warhol and Keith Haring. Those people tried to make it on the street level and then in clubs and galleries. At some point of their lives they gain patrons so they are able to expand their art and creativity. But in Japan, first of all, people don’t buy that much art and also, we don’t have that scene.” While Takuma frequently praises Kyoto, he also sees something lacking in the way the locals perceive art and culture. “For me the difference is that, whenever something cool is happening I can say that it’s cool without somebody else telling me. I think in Kyoto or Japan, it’s more of, ‘Oh, because somebody is saying it’s cool, it’s cool.’” Changing the attitudes of Japanese people to embrace “mixed culture” is one of his goals for y gion.

“If you mix cultures like art and music people who are not interested in art become interested, because they came for the other thing and accidentally find something more interesting. If I don’t provide those spaces that express not one, but two or three creative realms, it doesn’t expand.” For example, one event Takuma held at y gion was a pop-up of the restaurant Shokudou Ogawa sponsored by Shuhari Sake. The gallery space on the same floor of the building was holding an exhibition of the photographer and architect Hiroshi Sugimoto. The photos on display were Sugimoto’s Seascapes, large black and white photos of the horizon line of seas around the world. In addition to the food and exhibit, a rotating line-up of three local DJs played a mix of 90s hip-hop. Takuma makes sure that each part of an event held at y gion is strong on its own. The music isn’t an after thought and the food isn’t provided just because refreshments are necessary.

“If you respect local ideas that are going on in your local city that’s the global mindset, because people want to see that.”

The rooftop bar of y gion that hosts Sour Garden in the summer.

One instance of external validation to Takuma that his concept for y gion is working came from Robert Del Naja of the British music group Massive Attack. According to Takuma, Robert Del Naja spent $3,000 purchasing art at a collaborative gallery event featuring Kyoto-based artists Bakibaki, known for bold, geometric motifs, and Daijiro Hama, famous for his experiments with inky portraiture. Takuma tells me this story not to name drop, but to explain how this occurrence was proof of concept and how valuable that proof is for him to show local artists. “For y gion, when we did the event, we gave them proof that the art could sell and that time I felt really good because I could show artists that even in Kyoto, you can still sell art. I think that’s the highlight of the event that we did. And I can say it shows artists that they can be confident going out into the world.”

Takuma’s focus on having Kyoto-based artists use y gion as a launching pad is linked to how much the phrase “locally grown, internationally known” resonates with him. (He has been using it as the tagline for y gion.) Takuma answers my question about what he thinks the future of Kyoto looks like, “I think second cities that keep their authenticity or original ideas are going to be successful rather than big cities.” Second cities are the second or third largest cities of a country. Australia’s second city is Melbourne and Canada’s second city is Montreal. “You don’t need to be in a big city to have the latest information and in big cities it’s all the same brands, like Hermes and Louis Vuitton. Everywhere you go it’s the same product.” Takuma believes each second city has something no other city has. If people in those places continue to support their local artists and mix the culture inherent in their city, those things will have far-reaching appeal. “If you respect local ideas that are going on in your local city that’s the global mindset, because people want to see that.”

Part of the reason why Japan is interesting to the world is its rich history. Takuma sees both sides of the coin. On one hand, he says,“In the States, because they don’t have a history they can create new stuff.” He thinks its easier in America to innovate in industries such as entertainment, because there is less history to refer to. “At the same time, you are yourself because of the history. You need to respect history to expand or have new ideas, because if you forget where you come from you never know where you’re going.” It’s possible to be respectful of history while moving culture forward, but the Japanese government doesn’t always agree. “At some point you need to break boundaries and breaking boundaries to the government is not an option. To me, new creative ideas are really the driving force to have a new event or new ideas. The government structure needs to change, but it’s not happening.”

Takuma is not alone at y gion breaking boundaries and bringing his vision to life. He actively looks for people, artists, and brands who want to break boundaries in the same way he does. “Usually big department stores have to make money right away so you have to bring tenants that are popping but, as I said before, I want to do something that will last long. To do that you need to be really careful in selecting brands that have the same mentality as you.” Recently, y gion’s first tenant moved in: Jazzy Sport, a music collective, record store, and music label from Tokyo. Jazzy Sport being established in y gion is a significant milestone on the way towards Takuma accomplishing the goals he has set for himself.

He has a clear picture of what happens next. His humanistic goals are ordered from the people closest to y gion outwards. First, y gion becomes fully occupied with tenants whose mindsets are authentic in their desire to mix culture and bring people together as opposed to make money. Second, the building is constantly busy with visitors who understand what y gion is trying to do. Third, the artists y gion features achieve global recognition. Takuma declares, “That’s the moment I could say that this was successful.”

Y gion at night.