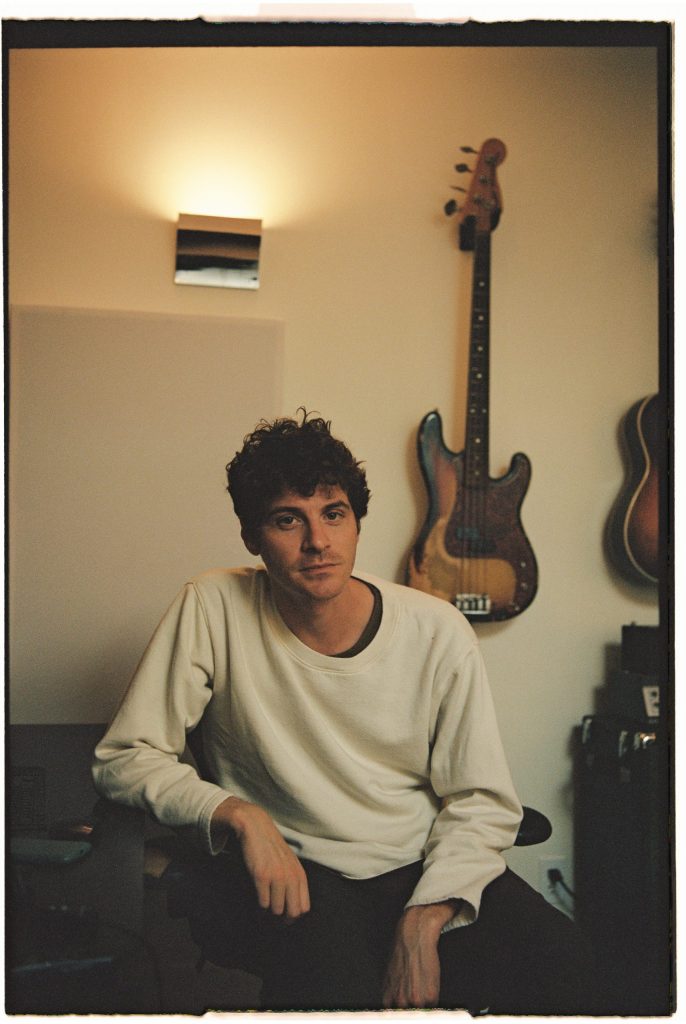

Emile Mosseri, the film composer and musician, leans back in his desk chair and reflects on the last two years. “It was a bit trippy. It was surreal,” he tells me, though not for the reasons you’re thinking. Not entirely. Just before the pandemic, Mosseri had a rush of life events: the first feature film he scored, Joe Talbot’s Last Black Man in San Francisco, had been released to high praise. He got married. He moved into the house we’re sitting in now. And then two other films he had scored were screened over two hectic days at January 2020’s Sundance Film Festival. “We were all there, just giving each other COVID, blissfully ignorant,” he jokes.

One of those films, Miranda July’s eccentric heist film Kajillionaire, would go on to broad critical acclaim. The other, Isaac Lee’s contemplative Minari, would, of course, go further, and take Mosseri along for one hell of a ride: it would be rapturously received, become a surprise awards season darling, and earn Mosseri an Academy Award nomination for Original Score. Soon, Mosseri was rushed headlong into campaigning, doing socially distanced press and panels with Trent Reznor over Zoom. Suddenly, there he was on Steven Soderbergh’s Union Station Oscars production. So, yeah – trippy and surreal.

If you’ve seen any of the films he’s worked on, you’ve heard precisely what drew Talbot, July, and Lee to Mosseri’s music: thrilling emotional clarity and tactile warmth. Contemplative, curious shapes sketched on vintage pianos or old guitars. Melodies that warble and shiver like a theremin careening through a mountain pass. Swelling emotion dressed as small, personal poignancy or big, universal wonder, and sometimes both at the same time. Gorgeously sculpted pop songs like Last Black Man’s “If You’re Going to San Francisco,” Kajillionaire’s “Mr. Lonely,” and Minari’s “Rain Song.”

Those pop instincts, along with Mosseri’s smoky coil of voice, are vestiges of his other musical identity: when I first met him in 2010, he was in the early innings of a long run as the bass player for The Dig, a Brooklyn-based indie rock band he started with childhood friends David Baldwin and Eric Eiser. Through The Dig, Mosseri would come into the orbit of artistic polymath Terence Nance: Nance directed a video for the band, and, in return, Mosseri composed music for several of Nance’s projects. In 2018, when Nance created his kaleidoscopic HBO series Random Acts of Flyness, he hired Mosseri to be one of the show’s five composers. That work drew the attention of Joe Talbot, who was looking for a composer for his first feature, Last Black Man in San Francisco.

I met with Mosseri in the converted garage studio of his LA home where he did nearly all of his 2021’s Oscar Zoom campaign. He also recorded – into his iPhone no less – much of the music that ended up on the final cut of Minari here. More recently he’s completed a collaborative two-part album that he wrote remotely with avant garde musical artist Caitlyn Aurelia Smith, a solo record, and scores for two more film projects. One of those films, Jesse Eisenberg’s directorial debut When You Finish Saving the World, took Mosseri right back to Sundance in January.

We listened to some of his latest work and talked about his busy last few years, how he chooses his collaborators, and where his career has been and where it’s headed. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What was it like having Minari take off the way it did?

Emile: It was cool. Just going through that at the same time that Isaac and Steven [Yeung] and Christina [Oh] were all going through the same thing and processing it with them was nice, you know? We’d all gotten together here in Koreatown after Sundance and had dinner to celebrate the movie in February right before the pandemic. And then we hadn’t actually all been in the same place again until the Oscars. That was the first time in 15 months that we had seen each other. So it was just surreal being all together. But it’s an experience I’m really grateful for.

Were you disappointed that the film didn’t get a full theatrical release because of the pandemic?

Emile: It sounds selfish or weird to even talk in those terms – about movies not being in theaters because people are losing their lives and losing their jobs and losing their livelihoods. Whether or not a movie is in theaters or on a laptop is not important. But you experience things based on your own expectations and experience. I come from a background of playing in bands, playing shows, as you know, and there’s something immediate about that. And although it’s not the same, the theatrical release of a film is the closest thing you have in the film world to being in a room and sharing a communal experience with other audience members.

It’s obviously not the same thing – unless you’re some kind of a psycho, you don’t go to the movies 30 nights in a row to see your movie, looking at everybody like, “What’d ya think?” – but there is something to be said for that experience. You get to have one or two experiences like that in the theater with people, which we got at Sundance, but we didn’t get it when the movie came out. Also, I recorded an orchestra and mixed it in surround sound, and then 99% of people that saw the movie were hearing the score through little tinny speakers. So most of the actual music isn’t coming through. That was sort of a hard pill to swallow. But, again, these are champagne problems.

It was really nice that the movie was celebrated and resonated the way it did despite that, and maybe in some way as a result of it too. I feel like any movie connects with people based on the zeitgeist and where the world is at. And I think Isaac made a movie that was very powerful and real. It’s not escapism. But in a way it was a feel good movie, too. It came out when it did and people connected to it for that reason, in part. And it came out at a time when fewer movies were coming out so there was more space for it, because it was really an underdog movie.

Do you miss being on tour?

Emile: Oh yeah. Dearly. I miss it tremendously. I don’t miss the lifestyle: I don’t miss sleeping in the van, or sharing a bed with David, or eating shitty food. And I don’t miss the two hours between sound check and the gig when you have to sneak off to have dinner, usually someplace cold and unfamiliar. And I don’t – I know this list is getting long [laughs] – but I don’t miss that stuff. But I do miss, very badly, the feeling of playing shows and the feeling of being with your friends those few minutes before you go on stage, and people are pressed up against the stage, and there’s a feeling in the air, like, “Okay, let’s do this.” That little pocket of time, those five minutes before, I miss that the most, I think.

How do you contrast your work composing scores with your more traditional songwriting experiences? How is it different working with filmmakers versus other musicians?

Emile: It’s more connected than I would’ve anticipated. For the film scores, it helps when the directors live in LA because they sit on this couch that you’re sitting on and we try stuff out. There’s experimentation. I can write a bunch of music in the spirit of their film and throw stuff up against the picture in different, unexpected ways and see what works. It’s like going fishing and seeing what you can catch. That’s really fun – even though they’re visual artists and I’m a musician, it seems very much like a collaboration.

So, it’s like songwriting, but of course there are differences. Playing music and writing songs with guys you grew up with – that’s a whole other animal. And working with Caitlin was really exciting, though that was a digital experience. It was also kind of a lifeline during the pandemic. I like that it wasn’t in service of a film. We made a two-part record, and it was sort of a vibe replenisher and creative life force during the pandemic. She was a new friend. We had become friends a few weeks before she left LA and collaborating musically was a way to continue our friendship and conversation.

I’m also curious about the transition from working with lifelong collaborators in David Baldwin and Eric Eiser to now working with different collaborators on every project. Has that been jarring?

Emile: It has been creatively rejuvenating, but both things have their benefits. There’s something really special about growing up with other artists and writing music with them for that long. Whenever I write music, I still wonder what they’re gonna think of it. It’s just built in. They’re the two people that I’m the most concerned about liking my music.

But there’s also something nice about working with new artists, whether it be Caitlin or, or Miranda or Joe, or Isaac, where it’s project based, so you’re going in with a fresh slate. It can be simpler in a way. It’s nice to have something new thrown at you. But working on films, it’s in service of this other artist’s vision too. Writing a score is not like making a solo album. I write every note, but I’m still writing it in reaction to somebody else’s story and in service of somebody else’s vision. And it can take time to get calibrated, whereas with Eric and David, we’ve been calibrated our whole lives. And I still work with them in different ways. They’re making brilliant music. They’re making some of the best music that’s being made now.

How do you come to a picture knowing you’re trying to communicate that other artist’s vision but also balance bringing your own voice to the project?

Emile: I think the trick is choosing projects where people dig what you do. Then if you get that part of it right, 90% of it just works itself out.

Ultimately, the goal is to have a lot of myself in the scores obviously, and that there be a thread through them. The goal is to have them all feel like they came from the same place, but maybe wearing different hats or dressed differently to serve the films they’re attached to. But I think the short answer would be just choosing projects where people come to you for your musical instincts. If they come to you for your musical sensibility and musical instincts, then you just have to follow those instincts. That’s what got you the job to begin with.

There is something to be said for some friction too. That can be really rewarding. I feel like it’s helped me grow, especially with Last Black Man in San Francisco with Joe. He pushed me out of my comfort zone musically in a way that I thought was really hugely beneficial to the film and just as beneficial to me as a composer in general.

— Emile Mosseri

Have the last few years been more creatively demanding than your years in The Dig? It seems like a real acceleration.

Emile: The thing about films is you’re required to produce a large amount of music usually in a short amount of time. So that’s a catalyst that’s built in. But it can also be misleading too: Homecoming, Kajillionaire and Minari we’re all released — boom, boom, boom — in the same year, but were worked on at very different times. And I think we wrote a lot of songs with The Dig that were never released. What you see as a consumer is just the tip of the iceberg versus what any artist chooses to share with the world.

I actually think about this a lot. You want it to be meaningful when you release something. I’d love to be the kind of artist that releases a lot of music, and all of a certain quality. You try to strike the balance of being thoughtful about what you release and how much you can release, but not being so precious that you’re choking off something that could be great and out there in the world, connecting with people. I think the trick is, whether it’s collaborating with other musical artists or visual artists, being selective about the projects you sign up for. Because either one – making a record or scoring a film — takes a tremendous amount of work and a tremendous chunk of your life.

It occurs to me that scoring a film is one of those jobs where you can’t do it unless you’ve done it before. How did you even begin to start doing this?

Emile: You have to kind of just be full of shit [laughs]. You have to just say you can do something and then figure out how to do it. That’s what I did with Last Black Man — I told them I could do this thing I really didn’t know how to do.

Random Acts of Flyness was huge. It was the reason why I was able to get Last Black Man, and the reason why I was able to do it at all. Terence, the show’s creator, he’s brilliant. I was one of five composers that worked on Random Acts of Flyness – there was Jon Bap, Nick Hakim, and Terence’s brother Nelson and Terence himself as composers. He’s such a great artist, but he’s a master curator, too. He’s really great at strategically using his resources to execute his vision.

And on Random Acts of Flyness, I had to figure out how to do a lot of different types of music. That show is so wide-spanning – it’s so sonically and visually adventurous and psychedelic. It’s also vignette-based. So I had to do a marching band version of Bitch Better Have My Money, and I also had to do a horror movie score for this sketch “The Demon of Jealousy”, and I had to compose for a string quartet. It was kind of a masterclass for being part of this world.

And I had worked with Terence in different ways since 2013. He’s the reason I was able to break into film scoring. He’d hired me to write some additional music for his first film after Flying Lotus scored it. That film, An Oversimplification of Her Beauty, is a masterpiece. And then he made a music video for The Dig. And then I scored some short films that he produced over the years.

He also was the first person I worked with that really pushed people in a good way. He pushed them to do better and better work. There’d be multiple revisions on something. He’s just a certain caliber of artist that I wasn’t used to working with and it expanded my creative brain and I’m really grateful to him for that.

And, Joe’s also like that. Detail-oriented, specific, and challenging to please. I tell him that it can be nightmarsh at times, but at the end of the day, it’s something that you’re grateful for because you grow as a result. Also it’s not actually a nightmare – It’s only really a nightmare if the director’s notes are making the thing worse. And in the case of Terence or Joe, their notes are improving the product.

It sounds like you’ve had such wonderful creative partnerships. It strikes me that you never really had a period where you had to just take a job to do it.

Emile: Well, in a way, I did take a lot of jobs. The ten years before Last Black Man, I was on the road and making records with The Dig, but I was also pursuing this: pursuing scoring, taking a lot of jobs, short films, writing music for commercials – writing bad music for commercials – and writing music for whatever films I could get my hands on. But the jump from Random Acts to Last Black Man was a big jump and made it seem like The Last Black Man in San Francisco was my first film. But I scored a lot of films before that, just not films that most people saw.

It’s a double-edged sword: on one hand, it’s nice to be the new guy, but then it’s also not exactly the truth. And I feel this actually more with The Dig. The idea that The Dig somehow didn’t exist [because I’m now a composer] is the thing that’s more complicated for me because The Dig did exist and we wrote a lot of music and played a lot of shows to a lot of people. It was something that we’re all tremendously proud of, and it connected with a lot of people. We didn’t hit it huge, but we built something over years and years that was substantial. So then to come out with a film score and have people write about it in a way that sounds like it’s the first thing I ever did is complicated. I’m grateful for it. I don’t take it for granted and I’m hugely honored and grateful to be in that conversation, but it also can feel a little dismissive if it’s written about in a way where it’s like I never did anything else. It’s like a whole life of writing and playing music can sort of feel dismissed.

What was your original entree into writing and playing music?

Emile: David and I met when we were ten years old and we played in multiple bands. We played in a Rage Against the Machine cover band and then that turned into a Dave Matthews cover band (laughs). We took that hard pivot, you know? We were in a band called Jackie and the Band. We had all kinds of terrible band names. We were the Jay Arthur Band. We were Honey Nut Roasted at one point. And then we met Eric when we were 15. So Eric, David and I have been making music together for 20 years.

I was playing drums at first and then I got a bass so that I could be in a band with David because they needed a bass player. And it’s funny, I played bass in bands for 25 years because that band needed a bass player at that time, and they were one of the only bands in town.

I also had a piano in the house and was sort of self-taught. And I was into film scoring as a teenager. I was obsessed with Edward Scissorhands and The Godfather and Being John Malkovich – I loved that Carter Burwell score. And I learned those sorts of songs, but I wasn’t classically trained and I didn’t take piano lessons, which I regret. I spent so many years of my life perfecting the art of the perfect bass solo, which is completely useless crap. I haven’t been able to bust one out in a long time [laughs]. I would much rather be a more accomplished pianist than be able to play a slap bass solo that I thought would make your head spin at the time. But nobody’s heads are spinning [laughs].

Now I compose mostly on piano, and in the last three years I did start to feel like I’m a better pianist than I am a bassist or guitarist. I’ve spent so much more time with the instrument now, and it sort of opened up to me over the years. And you start to embrace your limitations and realize that sort of defines you.

I’m learning to try not to clean up too much of my piano playing on the scores. I record a lot of the scores on the piano with the iPhone microphone. And Minari was recorded almost entirely on the iPhone. Sometimes I would use this mic and an iPhone and split them out. The fact that that score got recognized by the Academy and institutions like that – it was thrown together in such a scrappy way! They would be horrified.

You’ve mentioned in other interviews that Ken Sparling at Skywalker Sound has mixed all the films you’ve worked on. When he got those iPhone files, was he actually horrified?

Emile: No, no, no. Ken is actually the perfect example. I’m glad you brought him up because he’s a composer himself and he’s an amazing guy. And he’s very proficient and technical. He’s a pro. But he’s also a hip dude. He actually told me a great story that illustrates the same exact point: they were working at Skywalker on Punch Drunk Love, which is like my favorite score, my favorite movie – it’s one of my top five in both categories. And he said that they’d like that when they recorded, there was a scene where Adam Sandler trashed the bathroom. Do you remember that scene

Yeah.

He loses his shit and he trashes the bathroom at the restaurant. That scene was recorded so poorly that they thought it was unusable. It was so distorted and blown out. And then they rebuilt it with foley carefully at Skywalker, like beautifully recreated it. And Paul Thomas Anderson was just like, “Oh no, just use the other one.” And they used it, and it’s in the movie. And I re-watched it after Kent told me that story, and it sounds like a Flaming Lips drum sound. It sounds so cool. But it’s not clean or professional. There’s an aggression to the sound that translates through the microphones being overloaded and clipping. And that’s the emotion of that scene translated in the recording technique, or whatever you’d call it, of this poorly recorded audio. From a storytelling perspective it’s incredibly effective.

The more stories like that I hear, and the more I just talk to other composers that I admire, the more I realize it’s all just experimentation. They’re playing around too, and they are dealing with the same things that I’m dealing with. You get a little window into that with these kinds of stories, and that can be really empowering and liberating.

Like with Minari, there’s a piece of music that ends up in a prominent scene in the film – in the fire scene – where I recorded it the day I wrote it. In fact, most of the recordings that ended up in the score and in the film were recorded as I was writing them. And I tried to replay them cleaner and better and more polished, and it would never have the same emotional impact. So some of the sloppiness of the playing or the recording was something that felt like it found a home in the film in a way that was emotionally calibrated and connected to the storytelling. So I’ve learned that it’s okay. I’ve also learned to maybe just try a little harder when you’re recording it at first because it might end up in the movie.

David: Do you feel like technology has changed this job versus when Danny Elfman or Nino Rota or John Williams would score a film in the past?

Emile: At its core it’s more or less the same. I’ve seen videos of John Williams hanging out with Spielberg and playing the piano, playing the ET theme, like looking at the picture and just trying stuff. It’s amazing to see. That part of it is sort of universal and timeless. But how the music gets recorded and produced, I think, is changing. The biggest distinction is that it’s more and more common now for composers to write themes and music before they start shooting the film and editing the film. And I think that would happen back then, but I think it was way more common that a composer would inherit a locked cut or a rough cut of a film and then start their work. Even in the last few years, in my experience, for Last Black Man in San Francisco I got a rough cut before I started; before I even met Joe. And Kajillionaire was a locked cut. And then Minari and Jesse’s movie, I’ve written the music before they started shooting. That’s been happening for years, but I think it’s happening more and more now.

David: You’ve said before that you were brought on to compose for Kajillionaire pretty late in the game and it was a rush to finish that project. So Kajillionaire and Minari were pretty opposite experiences. Can you explain the positive and negative tensions of having to produce under those two circumstances?

Emile: There’s a benefit to both approaches. Kajillionaire, I was in a room with Miranda every day for five weeks because there was no time. There was no time for me to bounce stuff to picture, e-mail it to her, and have her send me back notes. I had to more or less write the music with her in the room, which was slightly terrifying, but mostly just exhilarating and exciting because I’m in awe of her and what she does. I’ve been such a fan of her’s for so long. But I think the intensity of that experience found its way into the score, which found its way into the film. Just the intensity of not having any time and having to trust your very first instinct. You don’t have time to clean it up too much. There’s sort of a pure signal from that. There’s no time to really stand in your own way. And that’s the biggest challenge any artist has, especially musicians.

But with Minari, because a lot of that music ended up baked into the movie, it sort of had the same effect: the music all came from one emotional place. Like 80% of the music that ended up in the film was written and recorded before they shot the film. So when I sat down with Isaac and Harry and watched the rough, very first cut of the film, as far as the composing was concerned, 80% of my job was already done.

David: When you started writing, did you at least know who the cast was so you could imagine the script come-to-life?

Emile: I didn’t. I knew Steven was gonna do it. And Y.J. [Youn] and Ye-ri [Han], I wasn’t familiar with their work. And nobody knew who Alan [Kim] was. How could you know how cute that kid would be? For Alan, watching the dailies even, watching him on camera, he was just giving Isaac gold in every frame. We went to set and watched them shoot certain scenes and it was exciting to see, “Oh, this is now a family.” But then watching the movie with Isaac, with it put together with those performances, with the music, and the sketches that I had at the time – even after reading the script, seeing the dailies, and knowing exactly what was gonna happen, it was devastating to watch the movie. It was really emotionally powerful and also kind of a trippy, profound experience to sit on a couch next to the man whose life and heart were being ripped out and put on the screen. And I felt the same way about Kajillionaire and Last Black Man. All those films are deeply personal films where the artist is really vulnerable. There’s a bravery to that. That’s really, really rare and special.

David: How was it working on films focused on stories about people from underserved communities in almost every case? Has that been an intimidating dynamic to step into?

Emile: I think so, in a way. It’s not lost on me that for Minari, I got hired and I’m not Korean. And most of the people that worked on the film were Korean. But with that one, it was important to Isaac that the music wasn’t Korean or American; it was something else. He didn’t want an Americana score. And he didn’t want it to be influenced by Korean music. So I think there’s a juxtaposition that is effective if the music is stylistically different but spiritually aligned. It can be an exciting combination of elements. Same thing with Last Black Man in San Francisco. It’s set in 2018, with the black community in this urban setting, but you’re hearing music that’s unexpected.

But it’s also complicated because I am sensitive to the fact that anytime I’m hired to do a job, I’m taking that job away from somebody else. And for people of color and women, the numbers in scoring are abysmal. They’re really low. I have complicated feelings about it. I feel grateful that I’m able to contribute to these stories that are meaningful and important and need to be told. But more than anything I want to make sure I’m honoring their stories. It can be a good way to motivate you to make work of a certain quality because the film deserves that. The story deserves that.

Ultimately, it’s nice to be part of things that are pushing that narrative forward and not slinging snake oil. So I’m really grateful for that, that I’ve been able to be a part of that. Random Acts too. And Kajillionaire. All these stories have been coming from underrepresented communities, but there’s a thread in all of them — they’re all very vulnerable and honest forms of storytelling.

— Emile Mosseri

David: All of these projects are so strongly set in a place. What research do you do to capture that?

Emile: I’m not really doing any research. I’m following the lead of the directors. If Isaac or Joe wanted me to research San Francisco music, or Southern music, eighties music, Korean music, whatever it may be, then I would do that.

But they’ve been more interested in trying to find that unexpected stylistic match that’s spiritually connected so that it makes perfect sense at the same time. I think that’s sort of a testament to the filmmaker, because the filmmakers are making these choices. They’re directing me to do it. Isaac made the choice that he didn’t want acoustic guitars, twangy slide guitar, and harmonica over images of Arkansas. He didn’t know exactly what he wanted stylistically, but he knew what he didn’t want.

It’s fun to be part of these projects where they push me to try to find whatever that thing is. Again — that’s all any of this is. Going back to that idea of imposter syndrome, or being full of shit when you take on a job: anybody’s full of shit when they take on a job and say they know how to do it. The whole art form is finding it. You can’t read a script and watch a movie and say “I know exactly what the score’s gonna sound like and what instruments I’m gonna use, culturally or stylistically what music I’m gonna reference.” You have some ideas of what your take might be, but it is always going to change because the whole joy of it is discovering it.

David: How do you figure out whether or not to fill open space in a movie? How do you not over compose those sections of the film?

Emile: That’s a testament to the director, too. I got really lucky with Last Black Man being the first movie that I did because there was so much space for music. And he kind of swung for the bleachers with the music in that one. He wanted big music and all these big montages. It was as though there were three films worth of music in that one movie. I benefited from that as far as that music being noticed; not just because it was good music, but because of how prominent it was in the film.

But overdoing it? There were certain scenes, too — there are certain scenes in all these movies, and in Last Black Man as well, where there were five or ten revisions on a single piece of music for it. And in the end we just ended up taking the whole piece of music out and it worked better. Where music goes is just as important as what the music is.

David: How much of your music scoring is now influencing your own songwriting now?

Emile: I think the scoring has influenced it, especially when thinking about different song structures. Strangely there are a lot of unfinished songs that can influence the film scores. So being a songwriter has influenced the way that I score films, but being a film composer is now also influencing the way that I write songs. I guess it has changed my idea of what is finished and unfinished music. A finished song doesn’t necessarily have to have a verse and a chorus.

David: Who makes the decision for what actually goes on the vinyl or Spotify version of what the soundtrack is?

Emile: I’m producing those, the soundtrack albums. I’m mixing all that and producing it. And I work with the director on sequencing and it’s actually a fun part of the process. It’s a lot of work. It’s like a whole other heap of work that you don’t get paid for. There’s a bunch of stuff that’s not in the film. You can’t just take what’s in the movie and just put it on a record because some of the things are like 10 seconds long. You have to stretch things out and shorten other things and add additional pieces. It’s important to me that the records feel like records you could listen to and not have seen the film and still enjoy. That’s the goal.

David: What else have you been working on?

Emile: The movie that I just finished I can talk about a little bit. Jesse Eisenberg wrote and directed it. It’s about a musician and his relationship with his mom. Julianne Moore plays his mom and the kid’s played by Finn Wolfhard. He’s amazing in this movie. The movie is really special. I’m biased, but I’m really excited about it. It was a really unique challenge because I wrote some of the songs that the character plays in the movie and that’s kind of connected to the score in this way. So it was a new challenge for me. Some things that the kid makes in the movie end up being reimagined in the score, and it’s sometimes unclear what the characters can hear and can’t hear. It was unlike any movie that I’ve done. And I love Jesse. He’s really a brilliant guy and really funny.

And then my record too, it’s still very early to talk about it, but I can’t wait for you to hear it. I’ll send it to you when it’s finished.

David: Do you feel like you watch movies differently now?

Emile: Yeah, I do. I can sort of see how it’s pieced together a little bit. But movies still really work on me. It hasn’t taken the magic out too much.

Emile Mosseri at his home studio.

— Emile Mosseri